Jeff Chimenti, John Molo and Roosevelt Collier Reflect on the Grateful Dead

There was a certain charming, funky magic about the Ventura County Fairgrounds, a soulfulness that made even the Grateful Dead’s demanding road crew not grumble too much about the crust of mud once deposited on the stage by the preceding day’s dirt-track race. So it’s the perfect home for the upcoming Skull and Roses shows April 6 through 8 this year, a gathering to celebrate Deadhead-edness and listen to the Golden Gate Wingmen (John Kadlecik, Jeff Chimenti, Jay Lane, Reed Mathis), Stu Allen and Mars Hotel, Melvin Seals and JGB, Moonalice, Cubensis, and a dozen other players of the Dead’s music, with flavors ranging from heavy metal (Shred is Dead) to Bluegrass (Grateful Bluegrass Boys) to Punk (Punk is Dead) and lots more. The promoter understands the Deadhead ethos, and is aiming at community; prices will be moderate, and the it will be a very cool get-together.

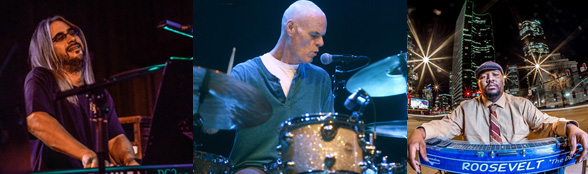

Since the key element in the event is enjoying our common heritage as Deadheads, I thought I would talk to the musicians about their relationship to the Dead’s music, which has become its own genre. There will be three more interviews next month about this time; we lead off with Jeff Chimenti, John Molo, and Roosevelt Collier.

Jeff Chimenti

Jeff Chimenti came to Deadhead notice with RatDog, and has stayed connected with Bob Weir ever since, playing in Furthur and now Dead & Co.

I started by ear, about the age of four — just basically growing up as a young Catholic school student and I had to attend church, and I started by mimicking what I heard the organ player do. Then I moved on – my sister was saying “You gotta play Elton John songs” – and I started to pluck out the stuff with two hands, and then a few years later I started classical stuff, formal training. That was about the age of seven.

I went to South San Francisco High School, and I got into the jazz band my freshman year. My parents had looked into it because there was this very good instructor named Mike Galisatus that was the band director at the time, and my parents took me to him over the summer after graduating 8th grade and I went to do an audition for him, basically. At the time, they did not take freshman or sophomores in the jazz band.

Leading into it, I was heavily into ragtime piano at the time, which lent itself to the jazz side, as far as harmonies and all that stuff. So I did my audition and then he put a jazz chord chart in front of me and I was like “What’s this?” (laughter), I couldn’t read it. But I started working on it, learned pretty quickly, and got into the jazz band my freshman year, got to be there all four years, and we had actually a pretty good jazz band, and did well.

We’d be playing in jazz festivals, and we’d hear Berkeley High, and they were like the top there – Dave Ellis, and Kenny Brooks – I’m sorry, Kenny was from El Cerrito. Even Josh Redman was in there, a host of guys. It was kind of nice over the years to meet and play with these guys way past high school, looking back to the days.

I started working gigs in high school – the band director had a good drummer and bass player, and put me in, and he started hiring us for casuals. So I was at it from the age of 13, and the next year was a little more, and a little more, and I started meeting other people, and so by the time I was 18, a dear friend of mine took me to the Jazz Workshop, which had just re-opened – the original one was where all the jazz greats played – he kind of dumped me off there and told me I was on my own – and I got to jam with a lot of people, meet a lot of great players, traveling musicians, got some good word of mouth, and just kept on finding gigs. And my phone got busy.

By the time I was approaching my mid-twenties, I was seemingly first call for acts coming in to Yoshi’s (at that time, the premiere jazz club in the S.F. Bay Area) and other major Bay Area venues, and so forth. Soon after that, I really hooked up with Dave Ellis and I joined his quartet.

Then he got the gig with RatDog, and I jokingly said, ‘If you guys need somebody to jam with, let me know.’ He called me two days later and said, ‘Guess what? They’re looking for a keyboard player.’ Really at that time, I didn’t know any Grateful Dead stuff, hadn’t even heard it. And Bob at the time didn’t even want to play Grateful Dead stuff (this is 1997), he wanted to be blues-based. Little by little things came trickling in, and we started pushing the issue with him, ‘Come on, man, these are great tunes, let’s play some of these things.’

I started writing out charts for myself, and learning as much as I could. I became the replacement for Johnnie Johnson (Chuck Berry’s pianist, for whom “Johnny B. Goode” is named), and I had the honor of him saying to Bob about me, ‘This is your guy.’ I got to play with him together, and I felt very blessed that he gave me the thumbs-up. The year before I’d seen television coverage of the second Clinton inaugural, and I remember thinking, ‘Hey, there’s Johnnie Johnson, hey, there’s Dave Ellis, hey there’s Jay Lane…”

Playing with Bobby meant learning his sound and his style of playing, because he’s really got one of the most unique approaches to rhythm playing ever – he’s like an orchestrator in there. So the challenge of what he’s going for, trying to work into that, working together, which became the understanding of how the Grateful Dead worked, how they were six individuals that formed one piece.

Listening to Bobby taught me a lot in that direction. I’m still learning, you know, it’s still a challenge. That’s the beauty of it. All of those guys are still looking for the next thing—it’s inspirational. And we just kept immersing ourselves in the catalogue – I had no idea, my god, the depth and diversity of the repertoire. It was pretty alarming, actually (laughter)!

My first big experience with RatDog was the Furthur Festival of 1997, playing these big amphitheaters, and encountering these huge groups of Deadheads – it was quite a shock. But I got it, early on, and I came to realize that it was like one giant community in a universal sense, people of all facets of life, all ages, all professions, it was really something to behold. They are everywhere, and it’s amazing. And thank god for ‘em.

(I quoted the late, great, G.D. crew chief RamRod, after a 12 hour day in a steamy Washington DC, saying “Well, at least it’s not a real job,” that working for the Dead could be hard, but it was something else, something special.)

I really miss RamRod, he was just a sweet soul. I got to spend a handful of years around him steady, and just seeing the relationship between him and Steve Parish and Robbie Taylor, that side of things, what those guys went through, and what they did for their side of the business, it taught me a lot.

Golden Gate Wingmen started off as a fluke. John K. (Kadlecik) was doing a solo run at Terrapin, and he reached out to Jay Lane and Reed Mathis and myself and said, ‘Hey, I’m doing this gig here, I’m going to do a solo first set, how about an electric second set? We’ll just get together and do a second set for the hell of it.’ The gig happened, and it was a whole lot of fun, and we were like, ‘We need to be doing this some more.’

It’s very periodic, and it’s dependent on people’s schedules and when we can make it happen, and it’s a fun project. It still follows that model – it’s been a while since we did it, so I’m looking forward to this visit to Ventura. It’s a really fun band, it’s just pure innocence at its best, you know what I’m saying?

John Molo

John Molo came to prominence as Bruce Hornsby’s long-time drummer. Late in the ‘90s he spent a year as part of Mickey Hart’s second Planet Drum ensemble, then joined Phil Lesh and Friends. He was also a member of The Other Ones.

My interest in music and drums began when I was seven or eight, but I didn’t start playing until I was in the 7th grade, getting into the local bands, and then I had a really good high school music program. My program kept me in school—a little bit of track and field, and sports, and the girls, but the main thing was I found my gift in music. I was at Langley High School, over there by the CIA, and I’m encouraged by my high school teacher to pursue drumming, get some private lessons.

My sophomore year in high school I was chosen to be in one of the local bands. This was right after the British invasion, I think they were called the Yorkshires. And we played a song by the Grateful Dead’s first album, “The Golden Road.” I thought the album cover was cool, and the song too, and we learned that, and that was my first G.D. song, this is 1969 or 1970.

I got really involved in jazz. Then I got asked by a group of friends to go down to a free concert at American University by the Grateful Dead (September 30, 1972). So I walked down to the soccer field, and I remember it as about three or five thousand people. And I hear the band, and I get what they’re doing conceptually—they have some songs, but they’re stretching out—but the audience, to me, was so intriguing. That was my first experience of, ‘Wow, I’d like to be able to play for these people because they seem to have a very broad appetite for music, whether it’s psychedelic, folkloric’—I didn’t completely understand it, of course, but ‘I’d like to be able to play for these people some day.’

That was my first sort of swerving into the Grateful Dead. Now I attend the University of Miami, where I meet Bruce Hornsby, and Bruce and I are ex-jocks really chasing the music thing hard, lots of jazz and R & B, and we hit it off really well, and in 1978 he decides to start the Bruce Hornsby Band with his brother Bobby. This was in his home town of Williamsburg, Virginia.

So I start doing shows with them, we’re doing some cover tunes, and Bruce is just starting to get into writing originals, and one night they say ‘We’re going up to the Mosque tonight in Richmond to see the Grateful Dead. You in for it?’ ‘Yeah, sure, why not?’ And I thought they were pretty good, and then I heard them again at William and Mary, and I thought, ‘Yeah, man, this is really good, I’m getting this.’

Fortunately with Bruce and Bobby, Bobby was the bass player in the band, and he had a nice Phil Lesh-esque bass style, he understood it. Bruce knew the songs were really good, so bang, by 1980, I was starting to get really familiar with the Grateful Dead. Like I said, I understood conceptually where they were at. Sometimes conceptually they might have exceeded their musical abilities, but through ambition and pure desire and guts, they got there so many times that I became a fan of the band.

And later, I was in my practice room one day, I thought, ‘Of all bands I could play with, who would it be? Well, probably the Dead’—not knowing that in the future Jerry was going to pass away and Billy deciding not to do a tour, opening the tour for me. So that’s how I swerved into the Dead, but my initial desire was to play for that audience.

Actually, the first time I played for that audience was when Bruce Hornsby and the Range opened for the Dead at Laguna Seca in 1987, and it was a real eye-opener.

We had a couple of radio hits, so we’d gotten some serious gigs, but we only had 15 songs, if that. We’d tried to learn how to play the album, and deliver that properly, because “The Way It Is” and “Mandolin Rain” had become pretty substantial hits—“The Way It Is” had gone to #1, and “Mandolin Rain” to #4 or #5, “Every Little Kiss” was in there, so we were just getting a lot of radio airplay.

So we show up at Laguna Seca, it’s an honor to be there, everybody’s super-nice. I can’t believe the number of people that I know, like rock nobility, I think Ry Cooder was on the gig. So we play the first day, and we were received fairly well.

The next day we came out, we didn’t really have another set to do, but as I recall, we played the first song or two that we’d done the day before, in the same order.

And there were two young gentlemen, they might have been like 19 to 21, and we could hear the crowd, and one of them says, ‘Hey Bruce, you’re not going to play the same set again, are you?’ And I could see a light went off in Bruce’s head, ‘Of course I’m not, this is a Grateful Dead crowd, we have to change up the set list.’

He immediately went into some blues thing, and we changed it up. Later in the set, as I recall, we segued from a song called “Red Plains,” into “I Know You Rider,” which has a similar tempo and tonal center. I remember we were playing at the Roxy in Hollywood and these two guys I played basketball with in my unemployed days told me that it sounded like we were going to go into a Dead tune, and sure enough—that was a winning moment for us, and kinda accidental, out of necessity.

But that was my recollection of the gig – it’s like, ‘oh right, this is that crowd we talked about, and now we have to deliver the goods.’ And I remember Ry Cooder’s great drummer, Jim Keltner, stopping by, and I visited with him. And he gave me a great compliment, he said that I reminded him of the great drummer Jim Gordon—I loved the compliment, and the validation of ‘Hey, we’re here, and the crowd’s OK with us.’

At those shows, of course, the Dead shot the iconic “Touch of Grey” video, and a friend of mine told me that he got dosed, imbibed something, and he said I’m just going to go cool out, passed out, and woke up and saw the Dead as skeletons (laughter)!

Twenty years with Bruce, that’s 140 dog years, and we’re still close, we talk regularly, about the kids, sports—we stay out of politics—but we try to keep it up and maintain that friendship. After that ran its course, I hooked up with Mickey and Planet Drum. He’s done more for drums and drumming than most —through the books, and accumulating an incredible collection and his knowledge of it. Hanging out with Giovanni Hidalgo (a great conga player from Puerto Rico) and Zakir Hussain (from India), it was such a learning situation on drums. Bruce and I, that was more a song thing, supporting the song. This was just drums.

And then the thing with Phil started up, and that was even more up my alley, because if you know me, I’m mostly a song guy, I really appreciate the great tunes. And with the catalogue of the Grateful Dead, plus all of classic rock, basically, I found Phil’s thing very appealing.

Phil’s thing really started developing when we got the Q together, with Warren Haynes, Jimmy Herring, Rob Barraco, and Phil. We had a great vocal combination. Warren is exceptional in many ways, but a lot of people don’t realize he’s one of the great harmony singers of all time. And Rob Barraco’s vocals were really so in tune, so vocally that band really stood out. So the Q got me firmly established in the jam band world.

I’m mostly focusing in on right now on California Kind (with Barry Sless, Pete Sears, Rob Barraco, and new face singer/songwriter/guitarist Katie Skene). She does some Winwood, we did Joni Mitchell’s version of “Woodstock,” she’s a really well-rounded individual with great song-writing skills. And I just went up to Terrapin with Phil, Anders Osborne, Jeff Chimenti, and it was a ball—and Phil’s still kicking it, man! Nine lives!

And so is Grateful Dead music, you know. As Bruce says, those songs have become hymns. Look at JRAD—that was originally going to be a one-off, and he’s 150 shows later…

Roosevelt Collier

Roosevelt Collier is a rising star and the newest volunteer in the army playing Grateful Dead music. He is part of the “sacred steel” music scene (Robert Randolph and the Family Band is the best known example) that came out of black Florida evangelical churches in the 1930s. Then he encountered a member of the Grateful Dead…

My church, the House of God, was based in Perrine, Florida, which was the next sub-neighborhood over from where I lived, a neighborhood of Miami, Richmond Heights. I was born and raised in that sound, sacred steel. That’s our genre of music, basically, from our church. For decades, it was only found in those four walls of the church. If you didn’t go, you didn’t know about it. Until this folklorist named Robert L. Stone stumbled upon some guys playing at a store, and he found out where it came from. He found the church and put a big light on it.

It was from the South. And the first CD of it was my Uncle Glenn Lee, the late Reverend Glenn Lee, he’s on the first one. There’s also a band called The Word, with Robert Randolph (steel), Luther Dickinson (electric guitar), and John Medeski (keyboards) that covers a lot of his stuff.

I started professionally after my uncle died of cancer, back in 2000. 2001 was like my “butterfly” show, coming out of the cocoon. I’d always played under him, but with him gone, I knew I had to take this step –‘This is my mission.’ 2002 was our first tour. I met Mike (League, of the jazz-jam Snarky Puppy, and also producer of Roosevelt’s new CD Exit 16), back in like 2009, and we’ve been friends ever since.

Being out of the church scene, we didn’t know any bands outside of the church. In school, I picked up on the song “Sugaree,” but I didn’t know where it came from. I never knew who the Grateful Dead was. Once we started touring on the jam band scene – Robert Randolph opened up the gateway for our style of music – we (The Lee Boys) hit the festival scene very heavy.

And in 2006, at the MerleFest (a roots music festival founded by the late Doc Watson to honor his son, Merle, who’d died in a tractor accident), we’re playing. We had a nice daytime slot, and we’re jamming, we’re going to church (laughter). We’re in it, and the crowd is with us. Well into the jam, we see a wave of people running over the hill, a couple hundred of them, and they’re going crazy. And I’m thinking, ‘I must be on fire,’ I don’t know what’s happening exactly, and I see this guy and his tech bringing an amp onstage. Don’t know his face, but we’re like, ‘Yeah, let’s roll with it.’ And the guy comes up and we are seriously playing –- we play the blues, then we’re playing the Blues Brothers’ song “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love,” and he is wailing and we’re having a ball. He’s killing it, the crowd is going crazy…

Afterwards, we jump offstage, and our manager says “Ya’ll have any idea who that guy was?’ We were like ‘No, but obviously he’s somebody pretty well known.’ ‘Yeah, that’s Bob Weir.’ ‘Who’s Bob Weir’” ‘Of course you don’t know, but let me tell you about the Grateful Dead…’ And I said, ‘The Dead? Like ‘Sugaree’?’ — ‘cause that’s the only song I knew. So that was my introduction to the Dead.

I really connected with the Dead’s music, because it’s spiritual like my own. It’s about improv, and you can’t play improv without some kind of feeling. These guys are playing from a place that’s inside of them, and that’s some type of spirit, some type of soul. And that’s very much like our church. Our church was 80% music, and 20% everything else. The basic church service—the praise service, a hymn, the offertory, the choir, the word, and then go home—wasn’t us.

Our church service lasted three hours, and 2 ½ hours was jamming. It was a rock show, with the pastor preaching in between. We believe in the praise through music, because music touches people. We don’t care what you believe in, because the power of music speaks to everybody. That’s a language known in every country, it’s the common language. It’s powerful. And we share that improv with the Dead and you know, the most fun you can have playing music is playing freely.

I never met Jerry, but then in 2012 my buddy Chad Edwards told me that Jerry played steel and I flipped my wig. Then I did some research, found these clips, and then I met Buddy Cage at a Warren Haynes Xmas Jam in Asheville. Buddy knew about sacred steel, and he’s such a nice guy, and we had a great rave about pedals, and tuning, and I learned a lot from him.

I’ll be playing 90% Dead tunes. I love “Sugaree.” “Franklin’s Tower” is awesome. I do a really funky version of “Shakedown Street,” it’s just groovin’. “Bertha” is everybody’s favorite. “Samson and Delilah,” too. “Not Fade Away.” “Mr. Charlie.”

And also, I did a record last year with this awesome dobro player, Andy Hall, from the Infamous Stringdusters, they just won a Grammy last Sunday for Best Bluegrass Album. We did a dual steel album and we covered “Crazy Fingers.”

.