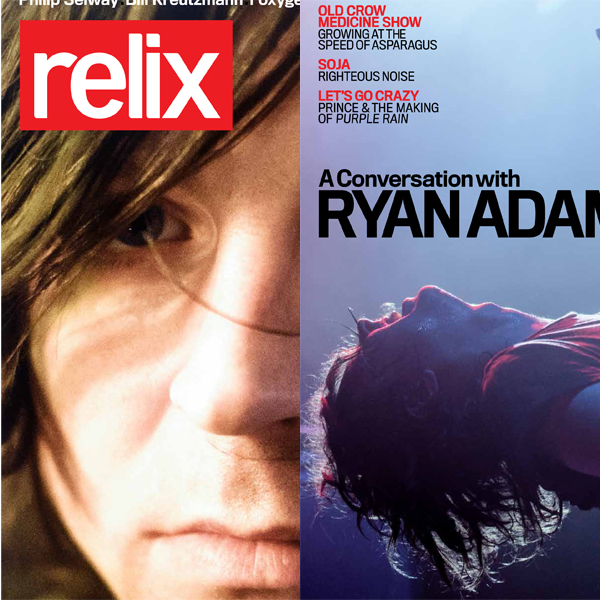

Ryan Adams on Playing with Phil Lesh and Jack Kerouac Inspiration (Cover Story Excerpt)

Yesterday on Twitter, Ryan Adams solicited Grateful Dead fans to send him videos of The Grateful Dead in the 1970s. Fans obliged, promoting Adams to discuss his thoughts on the band and geek out over some older videos. To add onto the occasion, here is an excerpt from our cover story with Adams where he discusses playing with Lesh, his thoughts on the Grateful Dead scene as well as the enormous impact Jack Kerouac had on him throughout his life. Subscribe now and get both the current issue as well as the 2008 issue featuring Ryan Adams and the Cardinals. Take a look at the story below.

You were inspired by Jack Kerouac. To what extent was he an influence on your automatic writing and is that something that you still practice today?

Kerouac was a huge part of my developmental process as was Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs and Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s beautiful poems—that was a huge part of who I was and who I still am today. There was a time when people would talk about Beat poetry like it was cliché and maybe they read On The Road, but then they didn’t get into The Dharma Bums or Doctor Sax or Mexicali Blues and all that stuff. I really lived that stuff when I was a teenager.

When I was 13 or 14, I first got access to that stuff because I had this beautiful, perfect storm of being able to live part time with my grandparents, who I just loved so much, and in a way they were my parents. I was one of those kids who had an extraordinarily negative relationship with my mother and my stepfather, but I’m very much like my father, who is still a part of my life. So I sort of lucked into this zone where my grandparents just loved me, they got me and I spent nearly all my time with them, and my grandmother really encouraged all of my questions. She wasn’t a super night owl but she went to bed around midnight or 1 a.m., and we would stay up in the summertime with the door open and the screen door closed in the kitchen in the back of the house, and play hearts and gin rummy. She asked me about these books and how they were forming my opinion of the universe.

I remember it vividly and romantically. There’s so much compassion and there’s just so much beauty in remembering these conversations that it’s nearly soul-crushing because I was shaped into being a little weirdo, free to ask a lot of questions and to be sort of goofy. They really encouraged me to be really open and creative. I drew all the time and sketched comic books and wrote short stories. We didn’t have a lot of money but she got me a subscription to Reader’s Digest, and I would read Edgar Allan Poe.

Very early on, there was a little tiny bookstore in my hometown [Jacksonville, N.C.] called The Book Exchange, and I found really cheap paperbacks of the Beat Generation stuff. The town I grew up in was right outside of a huge marine base, and they bought up all of the town’s beach property. The town used to make furniture but we sort of became townies whose jobs were basically to cater to the military. So I wasn’t growing up around other punks—although there were a few skateboarders, as I would become. Basically, I was this emotional child and, somehow, I was able to find this stuff. I knew about William Burroughs cutting up newspapers and writing a novel out of whatever sort of information that he thought was in there. It was a little bit like [the science-fiction novelist] Philip K. Dick’s idea of VALIS, living informationally. William Burroughs’ idea was that if you tore apart information and put it back together, the same information was inside of it and there was this operating subconscious language to human beings that you could find in the process. That’s heavy stuff at 13 years old.

There were a lot of summers where Night Flight and HBO—when it first came around—were very real to me, and I just consumed this material. I just consumed this information and I fell in love with information. I fell in love with making things, and I fell in love with drawing things. And then, I fell in love with isolation and other things that felt isolated.

It’s weird that I didn’t get into Springsteen. I think maybe because I thought it was too obvious or maybe because I heard Born in the U.S.A., which I really liked, but I didn’t know to look for the deep cuts so I ended up getting a copy of Maximum Rocknroll and Flipside magazine from this skater guy.

I also was drawn to esoteric studies. My grandfather was a Master Mason, and we hung out a lot. I would go down to the lodge with him as a child, and I was allowed to see some of the kind of rituals. I remember thinking how fucking cool it was—you know, guys with torches and swords and secret words and all this different stuff.

I looked at my own studio just the other day and realized I put in these black-and-white checkered floors that had to be diamond patterned, and the way that the furniture and walls were, I realized that I thought I was building my own Motown, but I built a Masonic lodge.

My grandfather’s Masonic life maybe edged me closer to the occult and esoteric stuff. But in a lot of these books, even in Edgar Allan Poe, I’ve noticed that there were these characters who would do automatic writing. It may even have been in Dark Shadows, which was my favorite show growing up, where you don’t actually write from your conscious mind. You sort of turn the lights out and get a piece of paper and put your pencil to the paper and you let other stuff through.

I’d say that maybe when I drank back in the day—when I used to try to record for as long as I could or stay in the studio and feel really spirited-up—that was a form of automatic writing for me. It was a way for me to process stuff that was beyond me.

Only recently—when I had my own studio again after I no longer played with The Cardinals and I was dealing with Meniere’s and I took this break because I was absolutely fucking sick—did I find out that I was actually this deeply spiritual person, who could not give you the exact frame of reference of what that meant but who had been disconnected from it for some time. And that it was probably at a peak, unconsciously, around Cold Roses and then, it dissipated completely up to the point where I was so sick that I couldn’t play.

So, little by little, those things dawned on me very privately and in a very wholehearted way, I started to embrace them again. The more faith I had in what I did—and the more appreciation I had for what I was doing—I realized that people jam all the time and I love that. I love just getting locked up in musical zones.

I’ve seen Phil Lesh do musical things that were tantamount, in my opinion, to a pagan ritual in which you literally saw an apparition. I’ve seen him do that musically. I have seen him destroy reality and look at me as if to say, “I’ve just destroyed reality.” I’ve seen it, and a lot of people who listen to his music or that kind of music understand that side is possible. So because I don’t know a lot of scales and I have my own version of that, I want to figure out how to do that with songwriting.

So this record—and the hundred-plus songs that are on tape at my studio—came from this new songwriting thing. I have my friend Marshall [Vore, a drummer] and there may or may not be a bass player. The microphones are on, the tape is rolling, and I just kind of start playing a song and I just trust that the chorus is going to come and that some of the words are going to happen. But I don’t do it once and go, “That was fun.” I do it for seven hours and, much like a jam, what I’ve noticed is when I find the thread—if I find the thread—I can take it all the fucking way. I can take it all the way out to the horizon and the water and then all the way back in to the beach.

Then, I go and listen back maybe that night or the next day and, quite frankly, there are complete songs like [Ryan Adams tracks] “Gimme Something Good” and “Stay With Me” and “Shadows.” The melodies are complete, the choruses are there and I literally can sit down and listen to what I’m saying and I sort of hear the line. Then, there are these places that are left open for me to fill in, and I assume that I am collaborating with my unconscious mind or the universe, which I’m a part of.

You mentioned Phil Lesh. Can you talk a bit more about the nature of that relationship?

I’ve had some incredible musical experiences with Phil—they’ve been out of this world. But I don’t really think that his fan base understands where I’m coming from. And, what’s beautiful is that I don’t really care—it’s not my scene. And what’s also great is that I’m a fan on my own. I listen to the bootlegs I want to listen to, and I make compilations of the tunes that I’m interested in. But I don’t have to be on a message board or be part of that scene. That’s not my scene. I came from a whole weird scene of music. I’m not compartmentalized: I’m not a Deadhead, I’m not a punk, I’m not in the hardcore scene, I’m not in a country scene, I’m not even in an alt-country scene. That stuff actually disgusts me. I just listen to the records and I make music.

So my time playing with him and jamming with him has been really beautiful. I would say that some of the most beautiful stuff that we were doing was the time I had in a rehearsal situation with him—some of the sessions where he played on my music in New York—sessions that people don’t even know about. Stuff I haven’t mixed down or left on tape in places where it would be safe. That stuff, to me, was always the shit and I always have a laugh with him.

Back to Kerouac—in certain respects I feel that On The Road is not altogether representative of his work. When I read a book like Doctor Sax or any of the Lowell novels, he comes across as a sweet man who is very conflicted about his spiritual life. Does that characterization resonate with you?

He had wanderlust. I think he was so inspired by the world, and he had faith and optimism that there was going to be this renaissance of romanticism. I kind of think that he thought he could conjure it himself and became unguarded. But the world is very bitter and people have been taught to not dream. Everything teaches you to be bitter in this society that we’ve built, like billboards that prime you for being sick by advertising medicine you’re going to need. You look at a culture of dreamers, guys who try to build clean cars who are destroyed by people who are making money from oil—or new movies come out rethinking the way people might make cinema, and they’re destroyed in the press or told that violent movies are responsible for kids shooting up schools.

I mean, this is a guy who had a lust for a romantic version of the United States and how it could be this transformative place. But he fell so in love with the tiger that he no longer could see the cage, and he walked right in there. It’s very difficult to look at him later in life and not see a man whose soul was destroyed—the Jack Kerouac that had to drink because he was destroyed. I think about that guy, and I think about how sad that is but, at the same time, people like Ginsberg survived and lived into late life making majestic satire and romantic poetry about his worldview. I think a lot about Jack Kerouac, actually.