The War On Drugs: Headphones On the Highway

Adam Granduciel is in the midst of doing one of his favorite things. We’re on a gear-hunting mission at Retrofret, a vintage guitar shop tucked away in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn, and he’s about to take a 50-year-old Magnatone tube amplifier for a test drive. “Have you seen Neil Young’s Magnatone rig?” he asks, eyes lit up. “It’s massive!” He scrolls through a set of photos on his phone and brings up a shot of a towering cabinet full of speakers that dwarfs the roadie standing next to it.

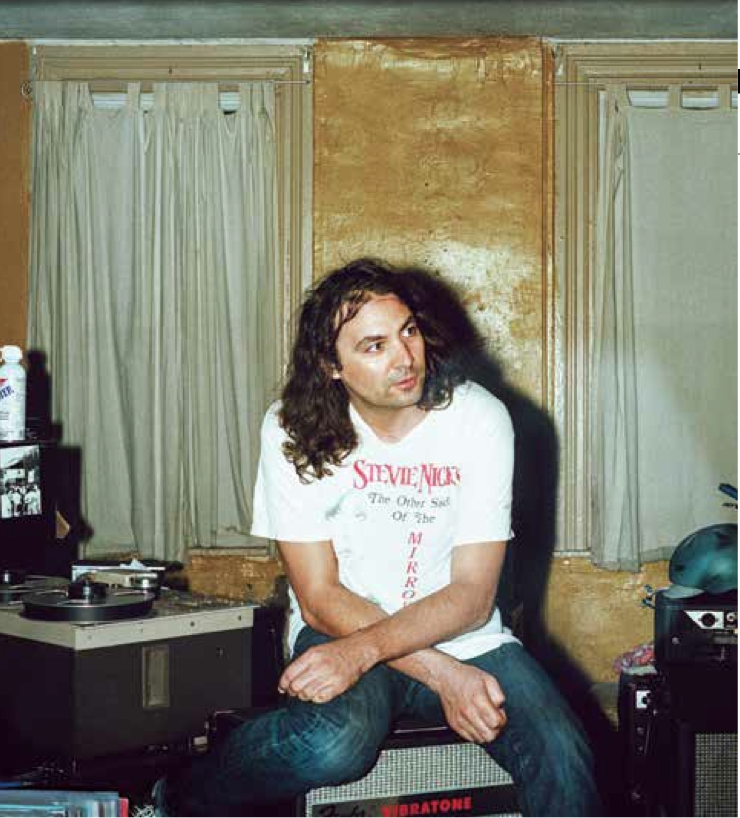

Granduciel pulls down a pristine mid-‘70s Fender Stratocaster from the row of guitars hanging above him, plugs in and settles his lanky six-foot frame into the tiny folding chair in front of the amp. As the Magnatone’s distinctive liquefied vibrato kicks in, he strums a progression of creamy chords that shimmer through the room like a gently undulating wave of rainbow-colored sound. The War on Drugs’ brand of alt-cosmic, road-trip boogie—a multi layered, echo-drenched, guitar-driven style with an Americana streak that draws liberally from the sacred marrows of Dylan, Springsteen and Petty—all originates in the quiet, contemplative noodling of the band’s frontman and lead songwriter. Granduciel and bassist Dave Hartley are visiting from their home base of Philadelphia, where they’ve been cooling their heels in preparation for a three-month tour that will take them across the U.S. and Europe, including sold-out stops at West Hollywood’s legendary Troubadour and the Austin Psych Fest. For Granduciel, the advance buzz is sweet vindication for all of the time that he and the band have spent together in the trenches since releasing 2011’s critically lauded Slave Ambient. Not only have they gelled with keyboardist Robbie Bennett and, of late, drummer Charlie Hall—into a well-oiled road machine, but with their Secretly Canadian release, Lost in the Dream, they’ve just delivered what Granduciel considers to be a creative breakthrough, and their first true “full-band” album. It is the “future rock classic” album—heady, heartfelt and free-spirited—that Granduciel has always wanted to make.

“I knew that I wasn’t gonna do this the same way as Slave Ambient,” Granduciel says. “I did most of that at home by myself, working on a tape machine and experimenting with it, then I’d transfer the tapes to Pro Tools, make a rough mix and dump it back to tape, and then overdub and transfer again—it went on like that. The process was great, but I just didn’t want to do that again.”

Instead, Granduciel started out by keeping to his usual experimental regimen, constantly building and tweaking song demos, but with the intention of turning the band loose in multiple studio sessions to make what he calls “an awesome-sounding hi-fi record.” And the description is spot-on: There’s an inescapable presence to songs like the soulful “Eyes to the Wind,” with its artful synth-washed textures, Bennett’s anchoring piano line and Granduciel’s confident lead vocal, urgent and up-front in the mix. “Red Eyes,” leaked in December, surges ahead on a motorik-style beat as it gradually spreads apart in an expansive wave of sound, recalling the rising tide of Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark.” In so many ways, Lost in the Dream is best enjoyed in the car, at night, cruising along a lonely highway.

“With the headphones on,” Granduciel interjects with a laugh. “Personally though, I just wanted to write bigger and better songs. They all started as demos, but the record turned into trying to showcase everyone’s ability to do what they do and still have a lot of fun in the studio and get deep into sounds. We’ve developed into a pretty close-knit group of musical friends over the years, and I didn’t really want to stray too far from that. It wasn’t like we had been traveling and playing any of these songs live, but I think more than anything, the touring just made everybody better.”

It comes through in the performances, which sizzle with the intensity of a band that’s playing live together in one room—and yet, as it turns out, this is the operative illusion of Lost in the Dream because nearly the entire album was built up from demos and overdubs.

The fact that it sounds so seamless, so dynamic and vibrant, is as much a feat of expert mixing (and the dauntless work of engineer and secret weapon Jeff Zeigler, whose Uniform Recording in Philly has become almost a second home to the band) as it is the ability of the musicians— especially the core trio of Granduciel, Hartley and Bennett—to tap directly into the spirit of the moment.

Those moments flow into the dream-like ambience of the album like eddies in a surging river. On the aptly titled “An Ocean in Between the Waves,” Hartley lays down a persistent, groove-pushing bassline over a drum-machine beat as guitars and keyboards, soaked in flange effects or rushed through spinning Leslie speakers, swirl in the background. When the real drums kick in, the song palpably shifts into another gear as Granduciel sings, “Feel the way that the wild wind blows through the room, like a nail down through the heart that just don’t beat the same anymore…” Halfway through the song, he takes a blistering and beautifully phrased guitar solo, cranking the heat up another notch. At more than seven minutes, it’s pure rock bliss by way of a meticulously drawn-out catharsis.

“When I first recorded the demo for that, it had a really dark, midnight vibe to it,” Granduciel remembers. “Then, we worked on it for about eight months, and it just flew off the rails. I knew it was wrong, but we just kept working at it. And maybe two weeks before the record was due, we pretty much went back and re-recorded it from scratch, essentially on top of the demo, in four days and got right to the heart of the song. To be fair, the guitar solo was actually from the original take, so I was able to fly it in, but almost everything else was at the last minute, trying to get this midnight feel that had been lost. It turned out to be a lot of people’s favorite song on the record, which is really cool.”

Lost in the Dream opens with “Under The Pressure”—a slow-cooking rocker flecked with spacey synth filigrees that recall Brian Eno in his late-‘70s heyday. At least three or four different guitar parts— layered and at times interlocked, with varying degrees of mutated effects— accentuate and build on the song’s deep- orbit trance state, as Granduciel cuts through the ether and sings, “When it all breaks down and we’re runaways standing in the wake of our pain, will we stare straight into nothin’ and call it all the same?” For many of his lyrics, Granduciel gets pegged for being semi-autobiographical— much like Dylan, one of his idols—but in this case, he insists the charge doesn’t stick. “It’s not like I was actually feeling

‘Under The Pressure,’” he says, smiling. “Eventually I would be stressed about making the album, but not at the time! It’s funny, because I started the demos for that song, and ‘Lost in the Dream,’ ‘Suffering’— really almost every one—between August and December 2012. We were still on the road, but we were just doing random weekends or festivals, and it wasn’t until February of last year, when we were gonna start recording the album, that I started to get a little stressed by the whole thing. So those song titles dictated the mood of the record, but in reality, they were written and conceived during what I thought was a pretty happy time. It is autobiographical, I guess, but it’s weird how that worked out.”

And yet for all of the changes that Granduciel rode through to make Lost in the Dream, he was always able to find sanctuary in the studio. The album was tracked in multiple rooms, including Brian McTear’s Miner Street/Cycle Sound Recordings in Philly and Water Music in Hoboken, N.J., but as Granduciel tells it, the sessions at Echo Mountain—a converted church in Asheville, N.C. that has hosted everyone from T Bone Burnett to Angel Olsen and Zac Brown Band—were especially relaxed. “We were never really searching for any specific sound,” he explains. “It was really just a matter of getting out of town. We’re also total studio gearheads, and I had a budget, so I wasn’t gonna go out and buy a Honda and then spend the rest on the record, you know? I love being in studios, and I love going to Echo Mountain for the Neve [console] or the Fairchilds [compressors]—totally unimportant, but it is fun. Mainly it was just nice to pile in the van and go to North Carolina for the week, cook dinner, make some music and have fun. You know, you sit in your room all day, working on rough mixes and waiting for that week to come when you actually have time booked, so when we finally made it down there, the ideas that were coming out in the moment were sounding great. Those were some pretty low- key sessions with a lot of spirit.”

As they look ahead to three months on the road with a long- awaited new album in their collective hip pocket, The War on Drugs are right where they want to be—honed and ready. “I’m really excited to get out there and play,” Hartley says, “because it almost feels like it’s the first time we’re a band. Adam and I have been playing together for seven years or so, but everybody who’s in the band now is really invested, and put a piece of themselves on the record, so they’re not gonna go out and play something that’s not in the spirit of the music. It’s interesting because in the studio, Adam keeps us on a short leash; he knows what he doesn’t want you to do. I think I prefer having very clear guidelines like that—but live, the leash is just as long as it can be, you know? We can get real exploratory and take some risks, which is a lot of fun.”

“I think that’s the exciting thing,” Granduciel says in agreement. “I know the recordings are special to people, and they have a mood to them, but with each record, the band has been just good enough to back it up. I feel like this time, it’s the dream band for us. Like having Charlie Hall on board— really all of us on board—and now we get to play the best batch of songs yet. Even when we do the older stuff…I mean, we played ‘Comin’ Through’ [from Future Weather, 2010] in Australia in December, and it was like, ‘Woo!’ It’s awesome, because it’s all spirit.”

For Granduciel, getting up on stage seems akin to being sprung from jail. It’s a hard- won payoff for all the late nights, meticulous tinkering sessions and near-obsessive playbacks that took him deep into another headspace for nearly a solid year. “The whole time I was working on this record, I was trying to figure out if music was making me happy at all. I’m still trying to figure that out. But it wouldn’t be what it is with anybody else playing on it, and live, it wouldn’t be fun for me to play with any other people. Everyone gets to do their thing—kind of like Pete Carroll with the Seahawks,” he laughs. “If you’re a freak, be a freak, you know? We’re all old friends, and everyone has these weird little idiosyncrasies, but it’s not like anyone ever has to keep it in check. I feel like the band allowed me to go on a journey in recording these songs, in all their various states, and that means a lot.”

And of course, whether you’re on a creative journey or an actual get-in-the-van excursion, you tend to pick up new friends along the way. The War on Drugs’ ardent following certainly noticed a surprise boost in their ranks during the band’s 2011 tour when, somewhat out of left field, Granduciel decided to throw a cover song into the set. Almost anyone who knows him would have thought Dylan for sure—but the Grateful Dead’s ‘80s hit “Touch Of Grey?” You don’t hear that one every day.

“It’s just a song that’s right up our alley,” Granduciel raves. “It sounds like a War on Drugs song. We started playing it in Indianapolis, and someone filmed it. I don’t think we even played the whole song—I didn’t even know the lyrics. We were just fucking around for like, 30 people there, and someone puts it on the Internet, and three nights later, we’re in Chicago and there are Deadheads in the crowd. It was as if they had an app on their phone or something, like ‘Touch Of Grey’ is being played tonight!” he laughs. “But it was the right song at the time.”

The National’s Aaron and Bryce Dessner certainly thought so. When news broke last summer that a long-rumored Dead tribute album, curated by the twin brothers as a benefit for the AIDS-fighting Red Hot Organization, was in fact a reality, the Dessners immediately confirmed that The War on Drugs would contribute to the project.

“Aaron’s been kind of a fan of ours for a couple of years now,” Granduciel notes. “Plus, he was coming to Philly pretty often to work on Sharon [Van Etten]’s record. So when he reached out, I told him we wanted to reserve ‘Touch Of Grey’ because I did want to record it. It’s been a little more challenging than I thought it would be only because I don’t want to just half-ass it. I want it to sound like our band, and at the same time, try to chase the spirit of the song because it’s got all the elements of War on Drugs music. It stays right on the beat, with some nice changes. So right now, the structure is there, the sounds are there, and when I take it to Jeff [Zeigler], we’ll pick it apart and make it pop.”

At 35, Granduciel is a bit too young to have seen the Dead in their prime, but the “I’m doing fine” message behind “Touch Of Grey” fits snugly into his ethos. For all of the idle, and frankly pointless, speculation that has grown out of trying to dissect his music and his lyrics—many have wondered if he feels lonely, paranoid and isolated, if he is a tortured artist seeking impossible perfection or a little of both—Granduciel himself comes across as an extremely easygoing and affable guy. He concedes that making Lost in the Dream was pretty far from a picnic, and there were times when living completely inside his own head for weeks at a time “could get a little weird,” but digging deep into the album reveals something else entirely. From the Kraftwerk-meets-“Young Turks”- era Rod Stewart vibes of “Burning” (which will likely open the band’s new set) to the inspired themes of the title cut (“Love’s the key to the things that you see…”), a very real sense of energy, expectation and hope shines through. If brazen, badass rock music is meant to do anything beyond stir our inner rebel, then it should at least make us feel good— both of which, in the end, are two sides of the same coin.

“That line from ‘Lost in the Dream’ wasn’t just a throwaway line,” Granduciel says intently. “It came out of that original moment at night in my house. I think it’s just about— you’ve gotta try to find happiness, and try to figure out your purpose. And if that will bring you happiness, you’ve just gotta surround yourself with good people, whether it’s your bandmates, or a romantic relationship, or social acquaintances or whatever. And I think again, I was singing a line like that before I was really living what the record became. And now I’m living it.”