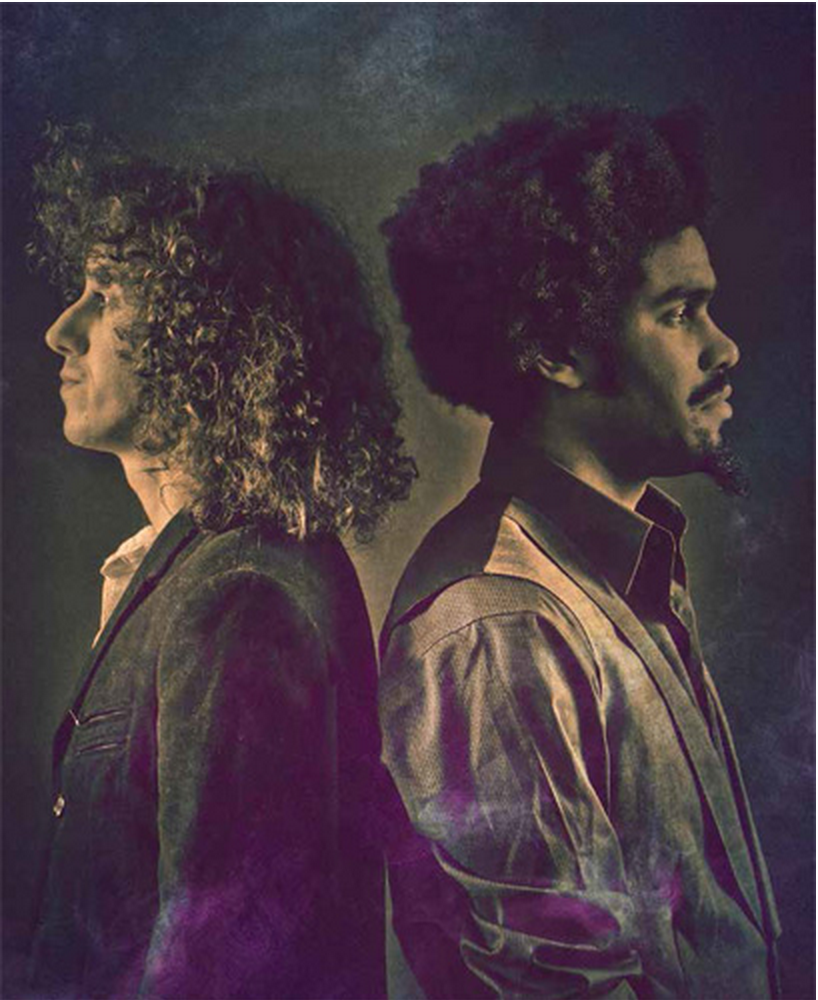

The London Souls: Rock-and-Roll Survivors

If you peruse the influences that most bands playing “rock” music cite these days, then you’ll find one or all of the following: Led Zeppelin, The Beatles, Cream, Jimi Hendrix. There is no criteria for putting those names on a Facebook profile, and most of the time those nods don’t accurately reflect a group’s true nature. But for Brooklyn-bred duo The London Souls, those artists are embedded deep within their DNA. In fact, guitarist Tash Neal and drummer Chris St. Hilaire had studied those classic-rock architects long before they founded their band.

“I moved to the city when I was a senior in high school,” explains St. Hilaire, who now shares a sibling-like bond with his London Souls co-founder. “Tash was one of the first musicians I met. We were with a small number of kids that were actually jamming and making music. We started jamming together in these little rehearsal rooms where they had beer machines.”

“I forgot about that,” Neal chimes in with a laugh.

Through the informal rehearsals, the duo realized that they had a unique connection. “There weren’t a lot of kids our age who were musicians that took it quite as seriously. We connected to music, spiritually,” Neal says. “We just vibed toward the same stuff and enjoyed each other’s playing.”

The London Souls oscillated between a trio and a quartet in their formative years, before ultimately settling on a largely twopronged attack. The band began touring around the many nooks and crannies of New York City, taking every gig they could. “We played college parties, birthday parties,” Neal says. “We started playing clubs in New York before we were 21.”

While honing their live craft, it became apparent that it was time to officially put something down in the studio. “We recorded as a four-piece, but it was never released,” St. Hilaire says.

The drummer says that failed initial recording is what scored them a publishing contract with EMI and turned the whole thing around. In an effort to make the most of their second opportunity at recording a debut album, The London Souls teamed up with a producer who had worked with such influential artists as Paul McCartney and Joe Cocker.

“We wanted to make a real record with a producer, and Ethan Johns came up,” St. Hilaire explains. “He was doing the early Kings of Leon record and he seemed like a talented guy.” [Johns produced the Nashville rockers’ Youth & Young Manhood and Aha Shake Heartbreak.] Through a shared connection with EMI, Johns ended up in the same room as the Souls—and that room happened to be Abbey Road Studios.

As St. Hilarie sums up: “It was a lot of playing bars and writing in between when we started and when we got to Abbey Road.” The London Souls’ 2011 debut was a raw, unabashed, authentic rock-and-roll record that kept the listener enthralled from the start. Neal burned through the speakers with his Jack White-inspired playing on the album opener “She’s So Mad” (think The White Stripes’ “Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground”) and St. Hilaire not only brought a crashing, Bonham-like drum sound but also the contrasting vocal harmonies that Neal credits as one of the main reasons the two got together in the first place.

It caught on like wildfire. “I Think I Like It” ended up in an Adidas commercial that featured then-NBA MVP Derrick Rose. The band traveled from festival to festival over the next two years—Mountain Jam and Joshua Tree Music Festival, among many others—igniting crowds and stages while maintaining their standing in the New York City music scene.

“I don’t think we were doing anything that other people were doing in New York,” St. Hilaire says. “We would play shows, but we would be billed with bands that just had nothing to do with us at all—and we stood out, which is cool.”

Neal adds: “Most of the bands we played with don’t exist anymore.”

Thanks to their workmanlike attitude, the London Souls managed to outlive many of their initial peer bands in the club ranks. Their regular shows at Brooklyn, N.Y.’s Cameo Gallery developed a cult following, and the band managed to pull in fans from the city’s often divergent indie, jam and rock circles. But then, in the spring of 2012, just as the band was about to break, Neal was the victim of an almost fatal hit-and-run accident on Bleecker St. and Broadway in New York City. On June 1, 2012, Tash Neal’s brother—and band manager—Sean took to the band’s Facebook page to confirm that Tash was in the ICU at Bellevue Hospital after undergoing brain surgery. All of a sudden, music and a blossoming career became secondary.

“Unpredictable,” Neal says regarding the effects of brain injuries. “When I woke up, I knew I was back because everyone was really surprised that I could talk. The doctors were freaking out. I just wanted to leave. I thought I was OK.” He lets out a retrospective laugh at that notion. “I didn’t realize half my Afro was missing.”

Neal underwent multiple brain surgeries, including removing a chunk of his skull. It often takes up to a year to recover from that type of injury—and that’s just the ability to walk and talk normally.

“I had my surgeries in September 2012 to put in the plate [Neal had a metal plate inserted into his head] and we played our first show on October 10.”

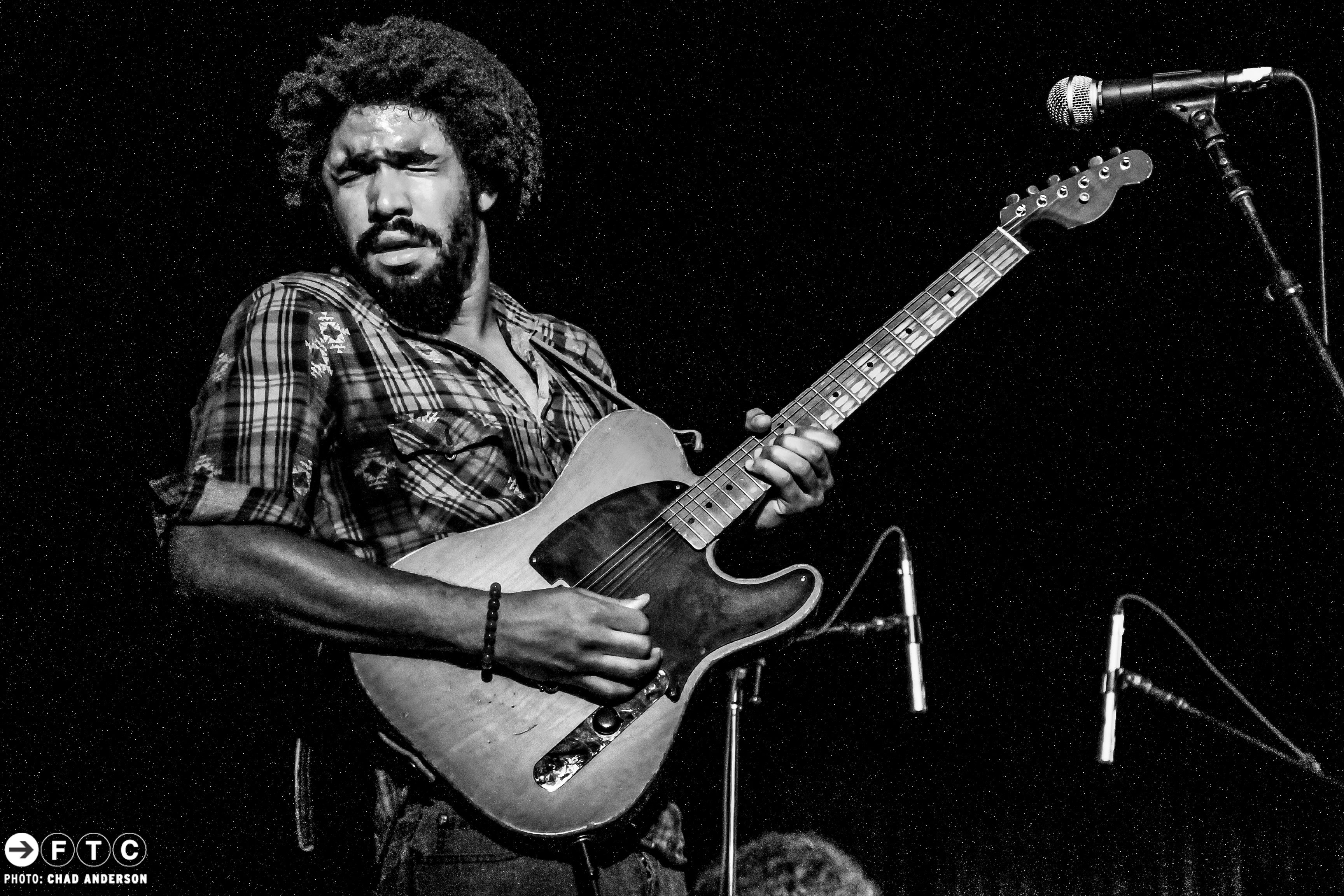

The guitarist remembers the first time he picked up an instrument after waking up, recalling his father sitting in the hospital room holding the acoustic guitar he writes songs on and has owned since he was 13—the first guitar his parents bought him. “I could play E, A and G and it felt right. I felt like myself. In my fingers, it just felt right. I knew that I was myself and that there was more music.”

St. Hilaire recalls the incident from the outside, saying, “I was obviously going through a lot, but hanging out and seeing Tash’s family and being there for him, I was like, ‘Whatever I’m going through pales in comparison to what the family’s going through.’ I thought, ‘Maybe we’ll have a band, maybe we won’t, but I’m glad this person’s alive.’”

The drummer jokes, “We had gone from a band of four people to three people to two people and then, for a couple days, it was just one person.” The comment draws an equally hearty laugh from Neal.

Music truly became their lifeline. Every night onstage was an exorcism for whatever demons remained, as Neal paved the road to recovery with every scream and solo. “Music can lift people,” he says. “Lift their spirits and lift their bodies in such a powerful way.”

The guitarist acknowledges that while stamina was an issue for him early on, that returned, too. So as Neal and The London Souls got back on their feet, literally and musically, it was time to focus on their highly anticipated sophomore effort. Instead of replicating the experience at Abbey Road with Ethan Johns, the band opted for a friendly face in producer and Soulive/Lettuce guitarist Eric Kranso for what would become Here Come the Girls.

“We’ve been friends with him for a long time, actually,” Neal says. “We met him at a bar in Williamsburg before the debut album we did at Abbey Road. He just strolled in with Soulive and we’ve been friends since then.”

“We’ve made him an instant fan,” St. Hilaire adds. “He’s a great supporter.”

Krasno took the band under his wing, booking them for Soulive’s annual Bowlive series at Brooklyn Bowl in March, for what was dubbed “The London Soulive,” a collaborative set featuring the two groups. On Jam Cruise this past January, The London Souls played on the pool deck in the middle of a heavy rainstorm. While most in attendance retreated to watch from under cover, Krasno was one of the handful who seemed completely unfazed by Mother Nature’s wrath.

“That’s our number one supporter right there,” St. Hilaire says. “That says it all.”

Over the course of two weeks, the band recorded 16 tracks, 13 of which ended up on the album. Neal and St. Hilaire played most of the instruments on the record, with some assistance from Krasno. The collaborative experience allowed for an authentic session that expands on the raw sound of the debut with a more slick, daring and versatile side of the Souls.

“We wanted to make a record,” St. Hilaire says. “With the first one, we had limited time and it was more about capturing what we did live—almost like playing a show. But with this one, we got to think about the layering and think about the sonic spectrum we wanted to create, and create a vibe that you can only create on a record.”

Their comfort level with Krasno—as well as the producer’s urge to push the young, blossoming group—led to a confident shift in sound. “On a musical level, he gets it,” St. Hilaire says. “He always stuck to what was best for the music, and he wouldn’t pull some fake shit like, ‘We should start with the chorus because that’s what the girls would like.’”

“When we went over the songs, we were so excited,” Neal adds. “We didn’t talk about it, but it was obvious.” The band included several tunes already in their live repertoire—“Steady,” “Honey” and “All Tied Down”—along with some new songs that show off the band’s versatility. “Hercules,” for example, is a foot-stomping acoustic track with a rollicking guitar line from Neal. Lyrically, the guitarist doesn’t reference his accident often, at least not directly, but he does so in this song with mentions of “leaving the past behind.”

St. Hilarie also takes a rare turn on lead vocals on the blues rocker “Bobby James.” It’s spur-of-the-moment decisions like that that show the comfort the band has found in the studio and, more importantly, with their own music. As Neal puts it: “The records come alive when you’re in the studio.” On Here Come the Girls, The London Souls breathe new life—quite literally.

Two days after sitting for this interview, Tash Neal found himself onstage at Manhattan’s City Winery with Amy Helm. Later that same evening, Neal and Krasno jammed with photographer Danny Clinch and Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello at Clinch’s “Walls Of Sound” exhibit opening at Milk Gallery. Neal and St. Hilaire have also shared the stage with the likes of Phil Lesh, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Gov’t Mule and The Black Crowes, further ushering them into the live music scene.

“It means a lot,” the drummer says. “Someone like Warren and Derek Trucks—they’re people that are older and wiser, and what they do musically resonates with us. It’s inspiring. It makes us step up and play better.”

Neal elaborates: “It says a lot about those artists’ generosity as well. They really are egoless people.” He tells a story about the first time he met Warren Haynes during a London Souls show at New York’s Mercury Lounge. “We were probably 22,” he says. “He was so sweet and nice and supportive and has been ever since. We’ve been really fortunate to meet a lot of our heroes and so many amazing musicians.”