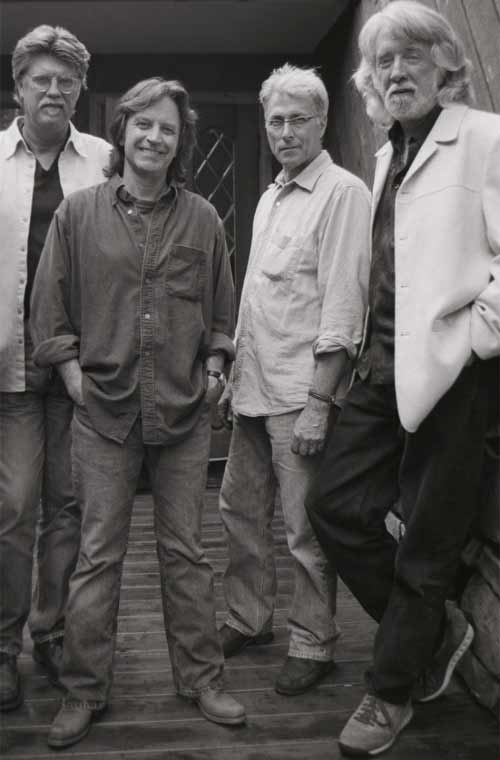

The Gold Circle: 50 Years of Nitty Gritty Dirt Band

“Do I feel occasionally that we are disrespected or overlooked? Sure. But on the other hand, we’ve had this great career. I don’t know what it is. It could be that we’re a moving target, musically. We cover a lot of stuff. We get bored just sitting still.”

“Do I feel occasionally that we are disrespected or overlooked? Sure. But on the other hand, we’ve had this great career. I don’t know what it is. It could be that we’re a moving target, musically. We cover a lot of stuff. We get bored just sitting still.”

That’s Jeff Hanna’s response when asked if his group, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, has been denied due credit for helping extend the arc of Americana, a distinction they share with bands like The Band, The Byrds, New Riders of the Purple Sage, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Poco and the Grateful Dead.

On the other hand, if Nitty Gritty Dirt Band had only instigated the unprecedented summit of country’s old and new guards with 1972’s epic three-record set Will the Circle Be Unbroken, then their iconic status would have already been ensured. That album broke new ground by paying tribute to those who had paved the way for the Dirt Band and their aforementioned contemporaries. It was about much more than two generations finding common ground; it was, in a very real sense, a cultural connection that cut through the alienation and distrust between the insurgents of the ‘60s and musicians who touted tradition. It was a revolutionary concept for bluegrass royalty, like master musicians Jimmy Martin, Roy Acuff, Mother Maybelle Carter, Doc Watson and Earl Scruggs, to share studio time with this bunch of former folkies from Long Beach, California.

“Doc was happy to join us,” multi-instrumentalist John McEuen remembers. “He was saying the folk scene was dying, and they were looking for new audiences. I figured if we could get these guys to play with us, we could introduce them to our crowd. Likewise, people were always asking us, ‘Where did you learn to play the banjo?’ It just came together the way it was meant to come together. It was magic. We started recording around the first of August and, six days later, we had 35 songs.”

“We were just hanging on for dear life. We were blown away and having fun all at the same time,” Hanna recalls.

Still, not everyone was convinced it would work. Hanna recalls their initial meeting with Roy Acuff in Nashville. “He wasn’t impressed,” Hanna relates. “It was the biggest ‘we’re-hippies-and-they’re-not’ moment. But, to his credit, he came to the back door of the studio a few days later, and when he saw what was going on, he said, ‘This ain’t nothing but country. I’ll be here tomorrow.’”

The chemistry flowed naturally but, then again, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band wasn’t nearly as radical as most of their West Coast brethren. While their musical origins were similar to mind-expanding bands like the Dead, Jefferson Airplane and other outfits that had evolved from traditional trappings, the Dirt Band never strayed all that far from their original influences. The band’s first four albums—their eponymous debut and its follow-ups, Ricochet, Rare Junk and a live effort, aptly titled Alive— reflected the sound of an eclectic bunch, one that mixed a love of old-time music with a penchant for both the frivolous and the profound. They also had a sense of the sounds that were echoing out of Laurel Canyon at the same time.

“What set us apart was that we didn’t have a steel-guitar player,” Hanna reckons. “We leaned a little more on a Cajun influence with a rock-steady beat and added in the bluegrass element as well. That’s where we carved our niche.” “We were a jug band in overdrive,” McEuen adds.

Formed in 1966, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band originally included multi-instrumentalists Hanna, Jimmie Fadden, Les Thompson, Bruce Kunkel and Ralph Barr. Their lineup remained fluid during those earlier days, with a number of ancillary members and fellow travelers coming and going—one being a 17-yearold Jackson Browne, who remained in their ranks all of six months, and others, like Bernie Leadon, Rodney Dillard, Johnny Sandlin and Chris Darrow, who would drift in and out, eventually achieving fame with other enterprises. This early incarnation of the band managed to score a regional hit with “Buy for Me the Rain,” as well as a part in a major motion picture, Paint Your Wagon, which found them sharing screen time with the film’s two stars, Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin.

McEuen—a whiz on strings whose ability to jump between guitar, banjo, mandolin and, later, fiddle made him one of the group’s great assets— arrived shortly thereafter. The band briefly broke up in 1969 but came back with a vengeance, courtesy of Uncle Charlie & His Dog Teddy, and, following that, All the Good Times—two albums that would more or less establish the template for the Circle album and all that would follow. The former not only gave the group—now down to a core of Hanna, Fadden, McEuen, Thompson and newer recruit singer/guitarist Jimmy Ibbotson—their first national hit with the Jerry Jeff Walker composition “Mr. Bojangles,” but it also spawned several other chart contenders, including covers of “House at Pooh Corner,” and “Some of Shelly’s Blues,” all of which put them on firm commercial footing.

“The Uncle Charlie album started our career in realtime,” McEuen says. “It was a collection of eclectic tunes. It was an entertaining set of music where every song was a surprise. It had the perfect blend of singing and song choices.”

The band was barely five years into their trajectory when the group’s manager— John McEuen’s brother Bill— suggested the idea of retracing American music’s roots with a summit of its elder statesmen.

“We went to see The Earl Scruggs Revue playing at this club in Boulder,” Hanna recalls. “So when we were driving Earl back to his hotel after the gig, John kind of popped the question: ‘Would you, uh, uh, uh, do a record with us?’ And Earl said, ‘I’d be proud to.’ A couple of weeks later, Doc Watson played the same club, and John went back with the caveat that we were doing a record with Earl Scruggs. Earl was our magnet. And from that point on, it kept evolving.”

“Not many other groups would risk their entire career by doing an acoustic album after having hits like we had done,” McEuen suggests. “If the Circle album hadn’t succeeded, we would have been dead in the water.”

Nevertheless, from that point on, they proceeded steadily, if somewhat surreptitiously. Thompson and Ibbotson departed in the mid-‘70s, replaced by a rotating cast of temporary additions before keyboard player Bob Carpenter joined the fold in 1979. Also, starting in 1976, the “Nitty Gritty” portion of their moniker was dropped, and they subsequently referred to themselves as “The Dirt Band” for the next five years.

“That was a mistake,” McEuen insists. “Why would you take 15 years of marketing and making records and then change the name of the group? They said, ‘Well, everyone calls us the Dirt Band.’ I remember we were getting on a plane and the stewardess asked us if we were in a band. And Jimmie said, ‘Yeah, we’re the Dirt Band.’ And she said, ‘Is that anything like the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band?’ It was the next day that everyone decided to change it back.”

More hits came later, including the single “An American Dream,” written by Rodney Crowell and featuring a shared vocal with Linda Ronstadt. However, it was their appearance (as “The Toot Uncommons”) backing up pal Steve Martin as he mugged his way through his novelty hit “King Tut” on Saturday Night Live that truly thrust them back into the spotlight. Likewise, their groundbreaking goodwill tour of the Soviet Union in May 1977 not only gave them the distinction of being the first American band to tour that region, but also allowed them to once again break barriers.

The ‘80s also proved to be a productive period for the group, particularly in country-music realms, thanks to such songs as “Dance Little Jean,” “Long Hard Road (The Sharecropper’s Dream),” “Modern Day Romance” and “Fishin’ in the Dark.” McEuen left and was temporarily replaced by Bernie Leadon. The new lineup released a sequel to the Circle album, Will the Circle Be Unbroken: Volume Two, in 1989, reuniting the band with some of the participants from the original recordings, as well as contemporary colleagues such as Emmylou Harris, Johnny Cash, John Prine, John Denver, Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman, John Hiatt and Bruce Hornsby. It brought the group a pair of Grammys as well as nods from the Country Music Association for Best Country Vocal Performance and Album of the Year.

“Some of the rock intelligentsia, and even some of our rock-star friends, dismissed us, but the folks in Nashville thought we were cool as shit,” Hanna maintains. “And we thought, ‘Yeah, that’s even better.’ Today, Americana is one big tent. It’s so inclusive. You just don’t have those turf wars that existed even 10 or 15 years ago.”

While a world tour in the early ‘90s brought Nitty Gritty Dirt Band further attention, surprisingly, it was a shout-out by President George H.W. Bush that helped bring them notoriety by default. During an awards ceremony in Nashville, Bush bungled their name by referring to them as the “Nitty Ditty Nitty Gritty Great Bird.”

McEuen rejoined the group in 2001 and, the following year, the group put out their third, and final, Circle set, Will the Circle Be Unbroken: Volume III, with a new mix of guests that included veterans of both the first and second Circle albums, as well as Tom Petty, Dwight Yoakam, Del McCoury, Willie Nelson and two of the band members’ offspring: Jonathan McEuen and Jaime Hanna. It reached No. 5 on the country charts, but interest from the pop landscape seemed to be waning.

Still, the group continues to tour at a steady pace, recently gaining new momentum through their 50th anniversary celebration. The band also just released a new live CD and DVD, Circlin’ Back, recorded last year at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. (“The Dirt Band’s tribute to itself,” McEuen says.)

Meanwhile, McEuen recently released his own effort, Made in Brooklyn, a collection of traditional songs reimagined along with special guests David Bromberg, Matt Cartsonis, Jay Ungar, David Amram, John Cowan, John Carter Cash and Steve Martin. Like the original Circle album, it offers another example of McEuen’s reverence for his roots. A revisit to “Mr. Bojangles” adds new eloquence and assurance, while covers of classics such as “She Darked the Sun,” “I Still Miss Someone,” “My Favorite Dream” and “Excitable Boy” provide an authentic acoustic tapestry for the album’s originals.

“The intent was to take the best elements of the Circle album and the things that I’ve learned by being in this band, and create a recording where the listener is taken on a musical journey,” says McEuen. “I told the other players that this was going to be like us making our own Circle album.”

However, McEuen says any other parallels to his “day job” are negligible. “Most of the Made in Brooklyn music is songs I’ve wanted to record for years, but nobody with NGDB was interested in it. I’ll just say this, ‘Guys, I wish we could have done this with all of us.’ But one guy in the band can’t say, ‘Hey, I’ve got 15 songs I want to do on our next album.’ I’m not saying it’s good or bad; it’s just what it is. But within the structure of the band, I do about a fourth of what I’m capable of. It’s very restrictive. I don’t get to produce, arrange or suggest what parts they should play. All of that is important to me. I made this record for Chesky because, as with all my solo projects, I had total freedom. It’s a privilege to record. I’m really glad I can, and I just had to. That’s our job: making things for people. That’s our purpose—my purpose—in life.”

For his part, Hanna expresses some hesitation about making another record. “The sales were pretty soft for our last album,” he remarks. “That was disappointing. We are our own record company, so when we make records, we’re footing the bill. It’s expensive. We have to wonder if anybody really gives a shit about albums these days. I think they do and, at some point, you have to do it. I’m hoping that when we shut down after this tour, we’ll get in the studio and cut some tracks—maybe just an EP. But making an album just sounds like such a big undertaking now.”

“Where many groups would quit because they weren’t on the radio or they find touring to be more of a grind, the Dirt Band still survives, if not thrives,” McEuen replies when asked the secret of the group’s longevity. “We could have quit, but thanks to Jeff and Jimmie’s ability to pick good songs, the support of our fans and record company, and the ability to try different styles of music, we were able to persevere. It was all about persistence.”

“Life on the road can be complicated,” Hanna concedes. “We all love to play, but I’d be lying if I said we love to travel. It’s not enough sleep. It’s bad food. But it’s part of the lifestyle, part of the drill. We all learned the pitfalls early on. We had our share of speed bumps back in the day when we were kids because we thought we were indestructible. Fortunately, we’re still all healthy and none of us act our age. So it’s been a really great ride. We got on this bus in 1966 as teenagers and here we are grown dudes—grandfathers most of us. It’s interesting looking back but it’s also great looking forward.”