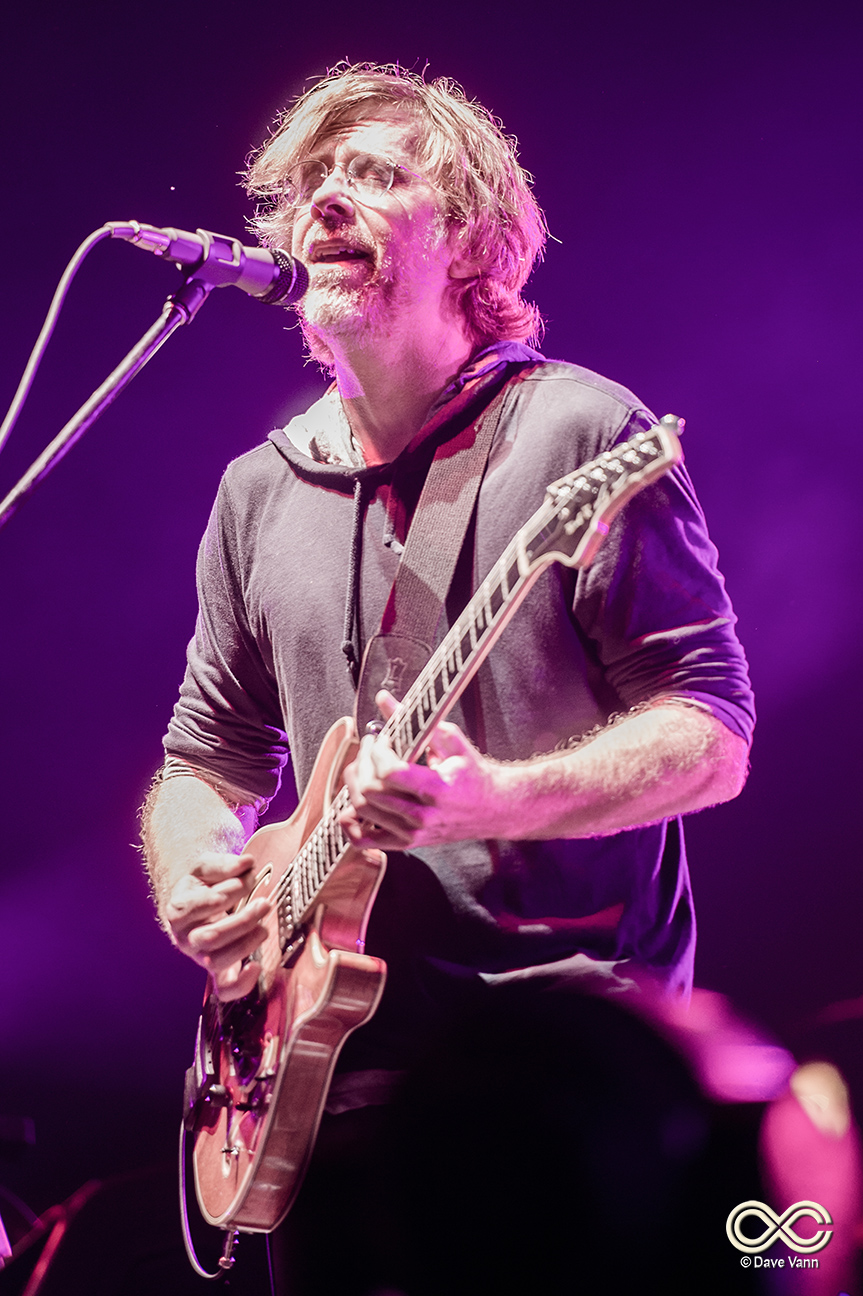

The Days Between: Trey Anastasio Reflects on His Time in Dead Camp

This article originally appeared in the October_November 2015 issue of Relix. To subscribe, click here.

This article originally appeared in the October_November 2015 issue of Relix. To subscribe, click here.

“OK,” Trey Anastasio says, leaning across a table in a New York café with a delighted gleam in his eyes, “here are four things I learned at Dead Camp.”

Dead Camp is the Phish guitarist’s euphemism for the first half of 2015, his short but intense spell as a working member of the band that has been a constant spiritual presence and creative challenge in his life since he was a teenager: the Grateful Dead. On January 5, Anastasio was in Miami, having just finished Phish’s annual run of New Year’s-week concerts, when he received an email from Phil Lesh, the Dead’s bassist, asking him to join him and the other surviving members of that group—guitarist Bob Weir and drummers Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart—for a series of July 4th weekend reunion performances at Soldier Field in Chicago. The concerts, dubbed Fare Thee Well, would commemorate two profound events, the 50th anniversary of the Dead’s founding in 1965—in the embryonic ferment of psychedelic San Francisco—and the 20 years since their final show—in that venue, on July 9, 1995—with Jerry Garcia. The band’s founding guitarist and all-but-official helmsman, Garcia died a month later, on Aug. 9, of a heart attack after a lifetime of battles with drug addiction, weight problems and diabetes. He was 53.

Anastasio—who saw his first Dead concert at 15, in May 1980 at the Hartford Civic Center in Connecticut—quickly accepted the invitation, then withdrew from all of his other musical work, including Phish and his Trey Anastasio Band. For the next five months, the guitarist, 51, embarked on a thorough, monk-like immersion in Garcia’s signature tone, expressive vocabulary and improvisational drive across a 30-year body of studio and live recordings. By mid-June, Anastasio was rehearsing in Northern California with the Dead and their other guests for this run, keyboard players Bruce Hornsby, a touring member of the Dead in 1990-92, and Jeff Chimenti, a regular presence in Dead-member projects. The education peaked—with transcendence—at two preview gigs on the Dead’s home turf, on June 27 and 28 at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, Calif., then in Chicago on July 3-5.

“I was always telling the guys in the Dead—I learned so much,” Anastasio says earnestly over breakfast on a recent late- summer morning, in a breakneck two-hour conversation regularly punctuated by staccato laughter and declarations of gratitude. “This is just four of the things I got from the experience. I already knew them,” he points out, grinning. “But now I really know them.”

The first: “There has never been a great rock band that hasn’t been built around an irreplaceable drummer,” Anastasio says. “That guy, in the Dead, is Bill Kreutzmann. I stood there for five days, watching people dancing. Bill is the heartbeat—Mickey, too. Together, they are one heart. Once the music started”—Anastasio hums the opening riff of “Truckin’,” the first song on the first night in Santa Clara—“I was like, ‘I know who’s driving this ship.’”

The second lesson: “Bobby is Mr. Slow Down,” Anastasio goes on. “He is patient, comfortable—no rush. Sometimes I’d be like, ‘You really want to play this song that slow?’” When Anastasio played the entrance lick in “Deal,” the last song of the first set on July 4, it was “at a Jerry Garcia Band tempo from 1982.” It was also “a little too fast.” When the song was over, Anastasio walked over to Weir. “I said, ‘That was too fast, wasn’t it?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ But he was totally cool. He played it anyway.”

Something else Anastasio discovered about Weir: “He’s a rock singer. Sometimes the music would get loose, a little floundering—no one knows where it’s going to go. Then Bobby would step up, like in ‘Samson And Delilah’”—in the first set on July 5. “When he started singing like that, boom, 80,000 people came together. It didn’t matter if it was in tune. That wasn’t the point. I could feel him unifying that stadium.”

Anastasio’s fourth revelation at Dead Camp: Forget the clock. “I love to jam,” Anastasio says brightly. “I love to jam long. But even for me, the time would come when I’d think, ‘This is too noodle-y. Let’s play the next song.’ I would do something, a lick, that gently alluded to it. Then Phil would look over at me and put his hand up, like, ‘What’s your rush, dude?’

“They weren’t done,” Anastasio concedes cheerfully. “That thing from the Acid Tests”—the 1965 and ‘66 LSD communions in San Francisco that were among the Dead’s first gigs—“was still there. ‘We’re not here to entertain you.’”

Anastasio pauses for a breath and some coffee. “All I wanted was for them to be happy,” he says of his duty in Fare Thee Well: filling, for a few nights, the large, deep hole left in the Dead and their road-trip nation by Garcia’s passing. “It was terrifying for me in that nobody can stand where he stood. But I was there in order for everyone to be together again, one more time, singing these songs.”

The guitarist has already moved on from Dead Camp. A week after the Chicago shows, Anastasio was rehearsing with his Phish bandmates—drummer Jon Fishman, bassist Mike Gordon and keyboard player Page McConnell—for their recent summer tour, a run distinguished by nine song debuts and Anastasio’s afterburn from Fare Thee Well.

“He came out of that ready to go, ready to play,” says McConnell, who saw all three shows in Chicago. “And when Trey is leading on guitar, that is when we are at our best.”

This interview takes place on a rare off-day for Anastasio this season—between summer Phish dates and before he goes back on the road this fall with the Trey Anastasio Band. He also has a new album, Paper Wheels, which he co-produced with steady collaborator and Pavement associate Bryce Goggin and recorded with TAB in 2014. If the record’s sunny jump and natural, breezy textures suggest a late-‘70s Dead artifact, then it’s because Anastasio made it “the old-fashioned way,” as he puts it. He tested the songs out live on tour, then cut them “Aretha-style—everybody in a circle, two takes.”

“All I know is writing songs,” Anastasio says, “and I love writing songs with my friends. That’s why this thing goes on and on.” He made “old-fashioned charts” for his band before taking the tunes for a road test during TAB’s early-2014 shows. “I had a day of rehearsal. They came out to my house—‘Here’s the song, play it.’ We went on tour, played everything at least once or twice. ‘Now you know the song.’ We came into the studio, set up the mics—that’s all it took, the whole thing.”

Paper Wheels was finished long before Anastasio received Lesh’s email. Ironically, the album’s driven immediacy—which also comes through in Anastasio’s fluid, gleaming-treble guitar solos in “Sometime After Sunset” and “Liquid Time,” the latter of which surfaced on Phish’s 2009 bonus record Party Time—sounds a lot like an affirmation of everything he took away from his Dead time. “It’s getting hard to draw lines in the sand, to know where one thing stops and the next one starts,” Anastasio confesses. He also affirms, “I can’t wait to go out and play these tunes.”  At one point, while recounting his Dead Camp lessons, Anastasio recalls another moment from Chicago, just before the first set on July 5, as he waited with Weir and Hart to walk onstage. “I told them: ‘You gave me my life. I don’t know how to thank you.’ They laughed. Then Bobby said, ‘I wish you had picked a better role model.’”

At one point, while recounting his Dead Camp lessons, Anastasio recalls another moment from Chicago, just before the first set on July 5, as he waited with Weir and Hart to walk onstage. “I told them: ‘You gave me my life. I don’t know how to thank you.’ They laughed. Then Bobby said, ‘I wish you had picked a better role model.’”

Anastasio first performed with a member of the Grateful Dead in April 1999. He was part of an early edition of Phil Lesh and Friends for the three San Francisco shows that marked the bassist’s official return to the stage—and the Dead’s repertoire—after his 1998 liver transplant. The guitarist has since worked with all of the surviving members of the Dead in various settings, including Weir and Lesh’s collaboration Furthur.

In a 2014 interview for Rolling Stone, I asked Lesh if Anastasio played even freer with him than in Phish. “I like to think so because that’s what I encourage,” Lesh replied. But the Dead’s music, at its best, was “freedom in context,” he insisted. “Rugged individualism is great. When that happens, you’ve got a solo. When everybody’s doing the weave, you’ve got collective improvisation.”

Lesh then summed up Garcia’s legacy in the Dead’s three decades of bonded searching—at once unprecedented and unfinished, cut short by the latter’s death— by saying, “He left behind a standard of quality to which we can aspire. What was it Dylan said about him? ‘He’s got his toes in the mud, and he can scream into the spheres.’ That range just gives me goose bumps thinking about it.”

In 1983, after more Dead gigs and levitation, the guitarist—born Ernest Joseph Anastasio III in Fort Worth, Texas and raised in New Jersey, the son of an Educational Testing Service executive and a children’s- book editor—made his live debut with Phish, which he formed at the University of Vermont with Fishman and Gordon. A year after that, Anastasio attended his last Dead show for the next decade. It was, he says now, “a conscious disconnecting— ‘We gotta go our own way. I’ve learned everything I need from this music.’”

That influence became an aura with weight as Phish—a gradually rising phenomenon in the jamband cult of the ‘80s and early ‘90s—exploded to arena status and mainstream fascination after Garcia’s passing. “The Dead has always been this thing in our existence,” says McConnell, who joined Phish in 1985, “especially for Trey as the guitar player and leader. It was always, ‘Is this the real deal? What do they really think about the Dead? Are they just copying them?’”

The parallels are striking. Just as Weir, Lesh, Hart and Kreutzmann strived and struggled to move on together in Garcia’s wake—in fitful reunions such as The Other Ones, The Dead and Furthur—Phish confronted their overwhelming success by going on hiatus in 2000, reuniting in 2002, breaking up in 2004, then starting over again in 2009 after Anastasio emerged from a personal crisis of substance abuse, arrest and community service.

Anastasio has now been sober for more than eight years. “Absolutely, that is something I thought about a lot,” he says, practically in a whisper, when reminded that he is nearly the same age that Garcia was when the latter succumbed to his drug and health problems. Anastasio declines to comment on rumors about Weir’s recent troubles—his collapse onstage during a Furthur show in 2013 in Port Chester, N.Y., and a subsequent retreat from touring in 2014. Anastasio will say this: Weir “is doing great. We were working out at his beach house, going for jogs.”

In a phone interview last February, a month into his Garcia studies, Anastasio exultantly described for me how he was internalizing critical details—“these iconic passing tones” in “The Wheel” from 1972’s Garcia, and the Bakers eld-country vernacular in live-Dead medleys of “China Cat Sunflower” and “I Know You Rider”— by memorizing licks in multiple keys and positions so he could “get it into my body.” The only way to know that music, Anastasio says now, “is by going deep. I learned the solos in three versions of ‘The Music Never Stopped.’ But that process…” He pauses, shaking his head in amazement. “If I was speaking right now to the biggest Garcia fan of all time, I would say, ‘However good you think he was, he was even better.’”

Amid his Garcia homework, Anastasio also got a crash course in the history of friendships in the Dead when he visited Weir and Lesh at their respective California homes in the spring. “It was demystifying, in a healthy way,” the guitarist says, “to hang out with people you saw up onstage when you were 16.” At Weir’s house, Anastasio heard stories about his early life in the Dead—how Weir commuted between Acid Test shows and his high-school classes the next morning—and the music that shaped the songs they wrote. Anastasio was surprised to hear that the Dead listened to a lot of Mahavishnu Orchestra during the making of Blues For Allah. “I was like, ‘Wow, that’s the same thing I listened to.’”

Amid his Garcia homework, Anastasio also got a crash course in the history of friendships in the Dead when he visited Weir and Lesh at their respective California homes in the spring. “It was demystifying, in a healthy way,” the guitarist says, “to hang out with people you saw up onstage when you were 16.” At Weir’s house, Anastasio heard stories about his early life in the Dead—how Weir commuted between Acid Test shows and his high-school classes the next morning—and the music that shaped the songs they wrote. Anastasio was surprised to hear that the Dead listened to a lot of Mahavishnu Orchestra during the making of Blues For Allah. “I was like, ‘Wow, that’s the same thing I listened to.’”

A few weeks later, Anastasio flew west once again to see Lesh. The bassist hosted a barbecue that Weir attended, and he experienced the seesaw dynamic between the two men up close. “Bobby was saying that when he started in the band, he was 16,” Anastasio says. “And Phil was 24. That is a huge difference in age. My take was that there was a big brother-little brother thing going on in a big way. And that relationship hasn’t changed much.

“But all four of them are brothers in the classic sense,” Anastasio goes on. “Any brothers will fight. But it’s usually followed by really deep love. They fall back into that role, then it’s: ‘Hey, man, I’m sorry I said that.’ Maybe they would snap at each other in soundchecks—like brothers. But once they started playing together, forget it, man. Fifty years—it’s right there in that thing. They can’t help it.

“I don’t know,” Anastasio says with a big, sheepish smile. “My lens might have been weird. I went in there so open. I felt I had a good perspective. I love all four of them. If there’s old stuff, I’m not part of it. And I have a lot of reverence for the band. But I also had my own band going on tour a week later,” he points out. “So I could see this for what it was.”

Anastasio reaches over his plate of scrambled eggs, holds up a smartphone and hits the “play” icon on the screen. “This is day one of rehearsal,” he says, watching a video he made at the Northern California practice space where he played with the Dead, Hornsby and Chimenti for a week before opening night in Santa Clara. The clip is a walking tour of the Dead’s massive percussion armory, the so-called Beast, with commentary and thundering demonstrations by Kreutzmann and Hart. Anastasio’s face is all delight and amazement as he looks at the footage, enjoying the memory again like a kid back in his favorite candy store.

“Now here is the first day in Santa Clara when I walked in for soundcheck,” Anastasio says, pulling up another video, shot as he walked through the backstage halls and rigging at Levi’s Stadium on the way to the stage. Even in smartphone fidelity, the racket—Kreutzmann and Hart rattling across their kits—is brutal. “It was deafeningly loud,” Anastasio con rms.

The five setlists in Santa Clara and Chicago were unique in the Dead’s performing history in that each one was written ahead of time, with a specific narrative intent, and performed without variation. Anastasio recalls sitting at a table with Weir and Lesh, talking about songs and order during one of their spring meetings. “Phil was saying that he really wanted to end this with ‘Attics of My Life’”—the tender, thankful benediction on 1970’s American Beauty and the final encore on July 5. “So they knew things like that months beforehand.”

The five setlists in Santa Clara and Chicago were unique in the Dead’s performing history in that each one was written ahead of time, with a specific narrative intent, and performed without variation. Anastasio recalls sitting at a table with Weir and Lesh, talking about songs and order during one of their spring meetings. “Phil was saying that he really wanted to end this with ‘Attics of My Life’”—the tender, thankful benediction on 1970’s American Beauty and the final encore on July 5. “So they knew things like that months beforehand.”

Eventually, Weir and Lesh split the evenings between them. The acid-era emphasis in Santa Clara on June 27 and the high-time ‘70s sequence on July 3 in Chicago were “kind of Phil,” Anastasio says. The more comprehensive histories on June 28 and July 4 were “kind of Bobby.” The last night in Chicago—a valedictory service that climaxed with the goodbye and renewal of “Unbroken Chain,” “Days Between,” “Not Fade Away” and Anastasio’s vocal leading on “Touch Of Grey”—“was both of them.”

But, Anastasio adds: “Conversations were happening daily,” right up to show nights. And those setlists kept changing “right until we walked onstage. I mean, it was so Grateful Dead.”

“Cut to the last night” in Chicago, Anastasio goes on. “We go to soundcheck, and they tell me, ‘OK, you’re going to sing ‘Althea’,” from 1980’s Go to Heaven. “I love ‘Althea,’ but I’m really nervous. It’s a real Jerry Garcia thing. So we play it in soundcheck. Phil starts it, and Bobby says, ‘It’s too fast, slow it down.’ Phil says, ‘No, Bob, it’s too slow, we’re going to speed it up,” Anastasio laughs. “This would happen every day. Meanwhile, I’m thinking a million Deadheads”—the crowd at Soldier Field and the multitudes watching the satellite broadcasts around the world— “are going to kill me because no one can sing ‘Althea’ like Jerry Garcia.”

Anastasio expected the song to be in the first set. As he went onstage, he noticed that “Althea” was not on the list. “Oh, we’re not doing it. I don’t have to worry about that. Then in the second set, there it is.” That’s when Walton’s counsel kicked in. “Phil was supposed to count us in. Now I know exactly how fast ‘Althea’ should go. I stood in front of Jerry countless times—I saw him play it. So in the moment, I turn to my left, to Bobby: ‘Look at me—one, two, three, go.’

“He couldn’t have done a better job,” McConnell says of Anastasio’s support and command—his poise under pressure— in Chicago. “When he started ‘Althea’ on the third night, it was so strong. That is the thing, I think, the Dead missed more than anything about Jerry. He was the anchor, the leader. And in moments like that, Trey took the ball: ‘This is part of my role. I have to be respectful but not to the point of cowering. I know what this is supposed to be, and I’m going to do it.’”

Lesh has since returned to focusing his attention on Phil Lesh and Friends, while Weir, Kreuztmann and Hart are out this fall as Dead & Company with Chimenti, Allman Brothers bassist Oteil Burbridge and, on lead guitar and vocals, John Mayer. The pop-star bluesman was at the Fare Thee Well shows, and he and Anastasio spoke backstage.

Lesh has since returned to focusing his attention on Phil Lesh and Friends, while Weir, Kreuztmann and Hart are out this fall as Dead & Company with Chimenti, Allman Brothers bassist Oteil Burbridge and, on lead guitar and vocals, John Mayer. The pop-star bluesman was at the Fare Thee Well shows, and he and Anastasio spoke backstage.

“I gave him some advice,” Anastasio admits—in effect, “to be John Mayer.” Anastasio actually kept asking Mayer about his own music: “‘Hey, man, how’s your new album? What’s the new song you wrote?’

“This thing he’s doing with them, it will go on for however long it’s gonna go on,” Anastasio explains. “What I was saying was: ‘You and I, this is not our band.’”

Here are three things McConnell learned at Phish Camp—their shows this summer—about how Fare Thee Well changed Anastasio as a musician. “First, he came on the road very warm,” the keyboard player says, “not cold from not having played for a while. He had just done something very intense. It must have been a huge relief for him to be onstage with Phish where we all know the repertoire, it’s all original members and we love each other. It’s all ready for him there to come out.

“Another thing, from a purely technical point of view,” McConnell continues, “is that Trey worked on his guitar sound a lot—the tone, the effects he started using, pickups, all that stuff guitar players talk about. Trey would play me recordings after a show—‘This is what this song sounded like two years ago. And here’s how it sounded last night.’ And I could hear it—this glassy, shimmering feel.”

And third: “Trey is more apt to play lower on the neck of the guitar,” McConnell says. “He said, ‘Jerry played down there a lot.’ And when you’re playing down there, you’re more apt to use open strings, which ring in a di erent way.” Everything Anastasio learned from playing with the Dead, McConnell contends, “is now affecting our shows.”

Grateful Dead songs were a big part of Phish’s early repertoire. They played “Bertha,” “Fire on the Mountain,” “Scarlet Begonias,” “Eyes of the World” and “The Other One” during their first few years, but Phish stopped playing the Dead’s music entirely in the mid-‘80s. Asked if, with all of this Dead back in his head, he would consider covering Dead songs with Phish again, Anastasio is courteously blunt. “I have nothing against the idea,” he says. “But after Fare Thee Well, I was like, ‘I have to get back to Phish now.’” Anastasio does mention one song from his teenage psychedelic awakening that he wants to perform with Phish: the first track on The Doors’ 1967 debut album, “Break on Through (To the Other Side).”

“Because that’s what this band feels like,” he raves, pushing his hand forward as if through a wall and citing recent highs, like Phish’s second set in Philadelphia on August 12—a spinout of escalating improvisation with almost every song, including the new jamming vehicle “No Men in No Man’s Land,” going for 10 to 20 minutes—and the band’s three-day Magnaball festival in Watkins Glen, N.Y. “Some of the music at Magnaball, I was like, ‘What the hell is going on? I have no conscious connection. I don’t understand what everybody’s playing.’ You’re in these jams, and they’re just going—waves of something—and everybody’s a part of it—Mike, Jon, Page, the audience, that guy we know in the front row. We’re all here, and the music

Still, Anastasio swears he will “go to my grave remembering the kind and cool look on Bob’s face” in Chicago when Anastasio started playing “Deal” too fast. “And the same with Phil’s little hand thing—‘Dude, no rush, chill out.’

“I just loved it, absolutely loved it,” Anastasio says, repeating himself as if in a trance. “All this planning and rehearsing, back and forth, tempos and all this shit, arguing about where you’re going to set up, and we walked onstage, and then it was the Grateful Dead. It was amazing. I was freaking out. I loved it.”