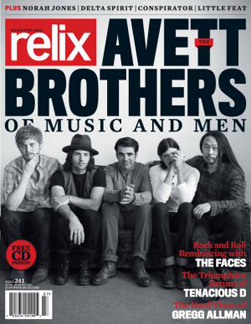

The Avett Brothers: Of Music and Men

Scott and Seth Avett are being cagey while discussing their circumstances in the middle of a sold-out two-night stand in Toronto. It was hard to fault them; expectations have been increasing the closer they’ve come to releasing the follow-up to 2009’s I and Love and You, the album that launched the North Carolina natives onto the world stage. They admitted that, for the first time, they’re conscious of things being a lot different now; that what they have achieved as a band is special and needs to be protected. But then Scott lets down his guard a bit, with a gleam in his eye.

“There’s this game I play with my wife where I say, ‘You’ve got two seconds to take a snapshot of your life right now and send it back to your 14-year-old self,’” he says this past May. “Then, I’ll pull a dumb face or something and say jokingly, ‘Can you imagine this is the way things are going to turn out for you?’ But in a serious way, sometimes I’ll look around at what we’re going through and think that if somebody showed me one second of this when I was 14, I couldn’t have imagined the path it took to get here.”

There was none of that self-questioning in evidence when The Avett Brothers, now a well-honed five-piece, took to the stage that night, with Scott, the elder of the two brothers, dead center for most of the show hammering at his banjo, his compact physique emitting the intensity of a denim-clad middleweight. By contrast, the long and lean Seth commanded the side of the stage with fluid energy, opening his soul on songs like “January Wedding” and coloring Scott’s lead turns with spot-on harmonies and six-string solos.

The Avetts certainly aren’t the only band to find success through blowing up an acoustic-based sound to arena-sized proportions, but what they displayed on I and Love and You was a masterful blending of the American folk song tradition with a contemporary punk sensibility. Opinions on the album were initially divided, but those who helped it land on the Billboard Top 20 have still not let it go three years later, as demonstrated by the rabid Toronto audience, nearly all of whom in attendance were less than 30 and equally split along gender lines.

A lot of the Avetts’ appeal has to do with the messages found in their songs, which are most often pure expressions of love, fear, hope and guilt, delivered with earnest small-town Southern charm and a sense of familial loyalty. It’s what their producer Rick Rubin heard on their prodigious independent output prior to signing The Avett Brothers to his American Recordings label in 2008. He was able to apply his unique sonic gifts to wringing out every last drop of these juxtaposed emotions on I and Love and You, and the album stands alongside Rubin’s work with Johnny Cash as his best within the roots genre.

A big reason why the Avetts are keeping mum about the as-yet-untitled new record is because they really have no idea what its release status is. Rubin’s co-chairmanship at Columbia Records (whose parent company Sony distributes American Recordings) ended this past January amid rumblings that he could no longer work with other executives who were angered by his freedom to produce artists signed to other labels. As of mid-May, Rubin was still deciding on a new home for himself and for American, forcing the Avetts to keep their anticipation in check as best they could. Then again, as Seth explains, the past three years have found the brothers growing out of a lot of their old ways.

*

" I and Love and You was sort of a rite of passage for us," Seth says. "It got us to a place where we could better use the tools at our disposal, and I think you can hear that immediately on the new record, sonically speaking. I haven’t let a lot of people hear the [new] record, though, which is the first time I’ve done that. Maybe that’s just me changing as a person. I was listening to a few things recently with a good friend, and when he heard one of the songs called ‘Live and Die,’ he said it sounded like it was from [2005’s] Four Thieves Gone, but with better production.

“That made me feel good, because even though there isn’t an orchestra or a big horn section on the new record, there are a couple of elements that we wouldn’t be able to do if we were recording in a house like we did for so long. Using those tools is exciting, and we’re a lot more comfortable doing that than on I and Love and You. There was a fair amount of adjustment we went through making that album, like doing 30 takes of something – ‘You mean the last 29 weren’t good enough?’ Our pace has always been fast when it comes to our music, but what we understand now is that making a record is an entirely different process than what we thought it was. It’s about translating a song to a listener, and you could say that making a connection to God or the universe is part of that.”

The Avetts agree that being around Rubin has brought out a spiritual side in them, as has been the case with many of the hirsute producer’s clientele. His overall influence on the Avetts has been undeniable, especially considering that they felt they were doing just fine before Rubin came calling. While lounging in the mezzanine of their Toronto hotel, Scott, clad in a jean jacket bearing crests from everywhere from Kansas to Australia, and his long hair and beard accentuating his hard stare, recalls what led to Rubin discovering the band.

“We’d put out four albums and were able to draw about three or four thousand people at home when we started getting some serious label interest,” he says. “It was really rolling, so we were thinking, why do we need anybody to help us? But Rick invited us to his house in Malibu [Calif.] and basically said that he loved what we were doing, and if it ever worked out that we could do something together, we should. As our friendship grew from there, I think we both realized where we stood with each other. We could let these other people handle the business while we talked about art and music, and that’s the way it’s been. We’ve got our little bubble. I don’t like to make people wait, but as you get older you realize that nothing good happens quickly, unless you can catch lightning in a bottle.”

Seth and Scott Avett at Freed-Hardeman University, 2008

It seemed as though the Avetts had indeed done just that the instant they decided to join forces after playing in separate bands throughout their teenage years, and briefly together in the punk outfit Nemo. Much of their inspiration to go unplugged came from their father Jim, a welder who played folk and country music on the side. Scott and Seth began raiding his eight-track collection, working up enough covers to start playing acoustic gigs around their hometown of Concord, N.C. just outside of Charlotte. This led to the creation of the six original songs that comprised a self-titled EP in 2000, whereupon they recruited stand-up bassist Bob Crawford, who became an official member of the group.

“For many years, it was unspoken between us that we’d put a band together,” says Seth, whose casual demeanor seems to embody Southern hospitality even in a foreign country. “Scott’s four years older than me, so when I was starting high school, he was graduating. There were just enough years between us that when I was ready to start my own band, he already had one going in the town where he was going to college [at East Carolina University]. But we kept saying, eventually we’ll have a band together. We started writing songs and mailing each other cassette tapes and having long phone conversations about it. As the younger brother, I’ve always felt that Scott was there to protect me ever since we were children, so there was always a sense of comfort for me thinking that we were going at this as a team.”

Seth adds that they forged their sound largely out of naivety, since they didn’t have much experience as a touring act. It was only when Crawford, formerly of garage rockers Memphis Quick 50, offered to book a tour that the Avetts got their first taste of what being a full-time band was all about. They learned quickly.

These Toronto shows took place at the recently re-opened Danforth Music Hall, a 1,500-seat former movie theater that has long been a jewel of the city’s live music scene, and the way the Avetts were in full control from the opening notes brought to mind a lot of the venue’s glorious moments. It wasn’t a surprise then to hear that they had been briefed about the building’s history. “Someone mentioned to us that The Clash played here,” Seth says. “That’s really cool.”

Reflecting on their early live experiences, Scott explains, “We really had no motivation to do things like actually book a tour. We were real homebodies, and still are to some degree. It’s like we were talking about the other day – give me a reason to go to New York or Boston or Toronto and I’ll go, but back then, we didn’t have a plan at all. We were totally immature in thinking that we could keep playing around North Carolina and eventually people would come to us. Maybe it was just being overconfident in our live show, because even then we knew that no matter how much exposure you got in the media or on the Internet, it doesn’t mean anything if you’re not able to connect with a roomful of people. We know that we can always get a gig somewhere on this planet.”

*

From Crawford’s arrival prior to the making of the Avetts’ 2002 full-length Country Was, the songs came at a staggering rate. The brothers released four more albums in as many years, in addition to two live discs and two EPs under the banner The Gleam. Joe Kwon – perhaps the world’s hardest rocking cellist – was added for 2007’s Emotionalism, completing the formal Avett Brothers lineup. That album marked the group’s entry into the national sphere, selling enough copies to earn a respectable placing on the Billboard Top 200 album chart, and cementing the brothers’ achingly confessional songwriting style with tracks like “Shame” and “The Ballad of Love and Hate.”

That directness remained at the core of I and Love and You, as songs like “Kick Drum Heart” and “Head Full of Doubt/Road Full of Promise” unabashedly proclaimed. The album’s title track is often a high point of an Avett Brothers concert – a chance for even the most cynical crowd member to feel a sense of communion that few other bands can offer. It’s hard to imagine the Avetts not playing that song at every show they do from here on out, and Scott suggests that the tone of their writing has broadened even further recently.

“Our songs are pretty straightforward,” he says. "We’re firm believers in the older you get, the more things need to be explained in a simpler way. It’s like walking into a kid’s playroom and seeing all of these big shapes and bright colors. We are aware now of when our songs are becoming too complex for our own good. So, when we’re feeling like we want to write a pop song, we just let it happen.

“In some ways, that’s just how life changes you,” Scott continues. “I’ve had two children since the last album [was recorded]. I just read a quote from Jay-Z where he said that he thought he would write a whole bunch of songs as soon as he saw his baby, but all he wanted to do was spend time with her. I could totally relate to that. Some of that feeling about becoming a father made it onto the new album, but there’s still that strong dichotomy between life and death. The shadows are very deep and the light is very bright. Whether that’s something engrained within the two of us, I can’t really say, but we definitely are able to switch roles quite easily.”

Neighborhood Theater in Charlotte, 2009

Sadly, that darkness encroached on the band last year when Crawford’s 22-month-old daughter Hallie was stricken with a brain tumor and had to undergo two surgeries after suffering a stroke and he was forced to take a leave of absence from the band. The news devastated the tight-knit group, but after eight months of relying on fill-in bassist Paul DiFiglia, the brothers say that they can see a time in the not-too-distant future when Crawford will return.

“On one hand, you want to reach out for selfish reasons and say, ‘We miss you man, we’d love to have you out here,’” says Seth. “But you have to recognize that what he’s doing is the right thing. So we’ve just been trying to hold it down while he’s gone, but he’s been starting to make his way out to more shows. He and his family have been going in the right direction for months now.”

Seth pauses before adding, “It’s just one of those unforeseen things you can never imagine when you’re a bunch of young guys getting together to write songs and stomp around onstage, trying to sell some CDs. Then it’s a decade later and you’re grown men with families and these tragedies start happening. I don’t know one person who hasn’t been affected by cancer in some way, but it still blindsides you every time.”

To illustrate, he again references the new song “Live and Die,” which clearly means a lot to the brothers and seems likely to be the centerpiece of the new album. It’s the sort of timeless message that the Avetts are focused on conveying now.

“Our attitude has changed somewhat in that we no longer feel like a song we’ve just written has to be recorded and released next month in order to be relevant,” Seth says. “In these 22 songs we’ve recorded, there’s one about a young child, and then there’s another about a relationship with the mother of that child six years ago. Songwriting isn’t really a linear thing for us anymore. They’re all kind of going on all the time.”

The brothers have, in fact, developed different working methods, even though each maintains a regular songwriting routine. Seth appears to be the one more at home in the studio though, with Scott spending a large part of his time creating visual art.

“I shoot myself in the foot when I say this because I start convincing people around me that it’s true when it’s a lie, but there’s a part of me that feels when a song’s written, then I’m on to the next song,” says Scott. “I haven’t engaged yet in pressing buttons or hearing what certain buttons do. But the older I get, the more I really want things to come out the way I’m hearing them in my head – and the only way to do that is get involved in the studio more often.”

On the other hand, Seth admits that he would be recording every day if he could, even though he adds, with a laugh, that doing the same thing every day would undoubtedly lead to him hating himself. “It’s like when we’re on the road. After about a month, you start asking yourself, ‘Who am I? Then you get home, and after two months you start missing the stage because that’s a big part of who you are. But I think about recording daily, because it takes a lot of practice to do it well. I feel so fortunate that we’ve been able to work with Rick and our engineer Ryan Hewitt. These guys are the best in the world, especially Ryan, from a technical standpoint. If you’re able to articulate to him what you’re looking for, he can make it happen. It’s like when I hear a Bob Dylan song that he recorded 40 years ago, it’s still so relevant to me, and that’s what we’re after.”

Unlike some artists, the Avetts don’t drop Dylan’s name lightly. At the 2011 Grammys, they took part in an unusual tribute to the man, sharing the stage with their British counterparts Mumford & Sons in backing Dylan on a rousing version of “Maggie’s Farm.” It served well as a symbolic passing of the folk torch, although the Avetts say that the music of North Carolina has always been in their blood.

“I think that there’s a rural part of us that we can’t escape,” Scott explains. “Even when you talk about people like John Coltrane, there’s a small-town part of him that was always there because of his childhood in North Carolina. And I’m not saying small-town as far as little, but [more as] a very focused way of looking at something that makes it digestible for everybody. I think Doc Watson is a perfect example of that. He’s got a very direct way of delivering a song. And as convoluted as John Coltrane could get, I think what he did was understandable whether you were a music major or not. For us, it was never so much bluegrass, which came from further west into Virginia, eastern Tennessee and Kentucky. When you get into the Piedmont area, where we’re from, the sound is based more in blues, country blues. Artists like Blind Boy Fuller came from there, and Charlie Poole.”

Seth chimes in, “I don’t know that there’s a sound, but there’s a spirit. In all of those Piedmont artists that we love, there’s something in their music that we’d like to have in our music, which is an authenticity and a catchy kind of poppiness, too. The pop music of that time – in the ‘20s and ‘30s – is obviously nothing like the pop music today, but its still fun to listen to and can deal with everything from paying the rent to meeting the Grim Reaper.”

Another of Seth’s analogies is unexpected, but makes perfect sense. “That spirit is in NASCAR as well,” he says. “[The famous driver] Richard Petty is from our area, and we knew a lot of Dale Earnhardt’s family growing up. The guys that we know from that world who became internationally famous started from very humble beginnings. It was success built completely on a work ethic and also a great attitude toward the fans. There isn’t a better example than Richard Petty of someone who always showed his appreciation to his fans, and we’ve taken that to heart.”

When asked if the Avetts would ever consider relocating elsewhere, Scott concludes, “We just love North Carolina so much It’s home base and definitely a sanctuary. I feel like we’re part of something unique to that part of the country. I feel like we belong there very much.”