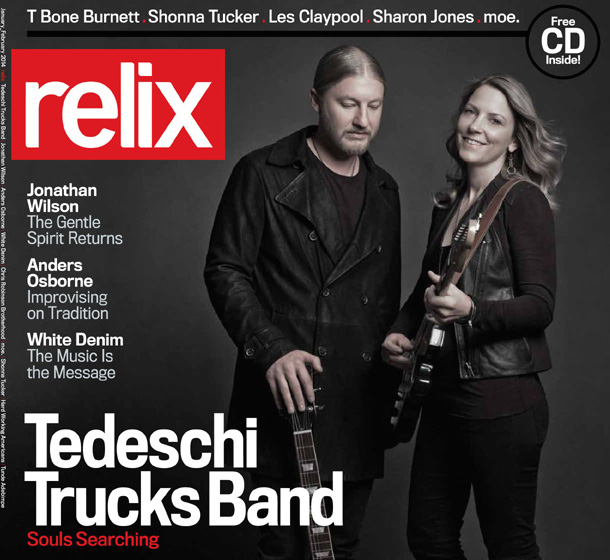

Tedeschi Trucks Band: Souls Searching

This cover story originally ran in the January_February 2014 issue of Relix.

“Nice. You can’t go wrong with Hendrix.”

Derek Trucks shares his enthusiasm at the outset of an impromptu listening party on the second floor of Swamp Raga Studios. Nestled comfortably within a plush chair while his wife Susan Tedeschi settles in on an adjoining couch, the pair salute the selection of longtime crew member and studio engineer Bobby Tis, who carefully removes Axis: Bold As Love from its dust jacket and dutifully cleans the album. Tis proceeds deliberately—a sonic cleric preparing an offering for the turntable.

He cues it up and the results are nothing short of a revelation. A true Jimi Hendrix Experience delivered as originally intended, with exquisite clarity and separation.

Though they have heard this album many times before, Tedeschi, Trucks and Tis soon chatter excitedly about their discoveries from this go-round. They marvel at the interview segment that opens the record, as Mitch Mitchell’s voice drifts to the right side of the room before abruptly careening in the opposite direction with a hard left. Eyes open and ears wide, they exhibit the animation and energy of like-minded music buffs.

Of course, they’re much more than that because the floor below is where Tedeschi Trucks Band have recorded two heralded studio albums, most recently Made Up Mind, the follow-up to the group’s 2011 debut.

“Every night, when we’d get done tracking, we’d come up here and listen to it on this system,” Trucks explains. “That way, we’d know we were not bullshitting ourselves. These things are relentless.”

“If you come up here with a half-assed mix…” Tis remarks.

“It exaggerates the wrong,” Trucks adds with a laugh.

By all accounts, these wrongs were few and far between during the creation of Made Up Mind. As vocalist Mike Mattison recalls, “The first time everybody was getting used to how this would work—finding a routine and finding a method—but with this record, that was already in place. It was like jumping into warm water.”

Yet while Swamp Raga offers a familiar, comfortable setting for Tedeschi Trucks Band, a place to call their own, it is not just a home studio.Rather, situated 40 yards from the house where the group’s married namesakes first settled in together and are now raising their two children, it truly is a home studio.

Swamp Raga would not exist but for the largesse of two renowned benefactors.

In late October 1999, a 20-year-old Trucks had just walked offstage following a performance with his own self-titled group at The Attic in Greensboro, N.C., when he noticed a few missed calls from a 415 area code.

“I didn’t know anybody from 415, but my number was the community phone for the band so everybody’s family would call if it was an emergency. There was a message from Phil Lesh, and I recognized the name but I couldn’t fully place it. I knew there was a Grateful Dead connection there but I didn’t know that stuff at all.”

Trucks returned the call and eventually accepted a two-week stint of Phil and Friends dates, stepping in for guitarist Steve Kimock, who had departed mid-tour. (Trucks originally indicated that he would need to postpone his involvement by a few days to honor prior commitments with The Derek Trucks Band, but two Deadhead club owners agreed to postponements as personal favors to Phil.)

“Those two weeks on that Phil gig were pretty amazing, going in pretty green to the whole thing,” Trucks remembers. “Every day, I would get a cassette tape of the Dead doing versions of tunes we would play that night, so I would sit down with headphones, make crude charts and then, I’d just wing it. No one plays like Phil. You’d know where he was going—he would spell it out—but it’s all improv and it’s all him taking it to different places. It was a lot of fun just following him.

“Learning that material, you get a quick appreciation for what’s great about it. I think people underestimate how unique the songwriting was with the band. It’s pretty advanced stuff harmonically; there’s a lot going on. And Garcia was one of a kind. The connection he had with Phil and [Bill] Kreutzmann—that trio especially—when you listen to the tapes, it’s like a band within a band. When these three guys lined up, it was like this little sports car inside of this really loose Salvador Dali painting.”

At the close of his Phil and Friends run, Trucks, who was still living with his parents, returned home to find a check in the mail for his efforts. However, upon opening the envelope, he was reluctant to cash it, fearing that there may have been an error. Trucks had agreed to a salary that he believed was a lump sum for the entire tour, yet the check was 12 times that score. After Phil’s office validated the amount of the unexpected windfall, confirming that the agreed-on compensation had been for each gig and not the tour in total, Derek decided to go house-hunting. Trucks and Tedeschi were dating at the time and he invited her to join him in the pursuit, which resulted in the purchase of the house along Jacksonville’s Julington Creek where they still reside today.

Their studio was a product of Trucks’ period on the road with Eric Clapton in 2006 and 2007. Eager to spend more time at home, he envisioned creating a rehearsal space in his backyard for The Derek Trucks Band. So he grabbed a legal pad and a measuring tape, jotting down a rough outline of a small building that could replace his fishing shack in the backyard. “I remember showing this to Bobby and he said, ‘Let me show these to my dad,’ because his dad [Bob Tis] builds studios, and I got back these proper drawings for a room. The timing was great. The Clapton tour had just happened and I said, ‘We’re going to pretend this didn’t happen and we’re building a studio.’ No new car, every check would go to David [his brother, the second of four Trucks children—Derek is the eldest followed by David, Duane and Lindsey], who was overseeing the project. We had a lot of friends and people cutting us deals on anything they could but it was still expensive. We cut corners without cutting quality. My dad and brothers did the roof.”

“I soldered most of the stuff in this place myself,” Bobby attests, “because I had spent all the other money. We all went for it because that’s what it took and it’s been real rewarding.”

“Everyone went beyond the call,” Trucks affirms.

If you build it they will come.

Given Derek and Susan’s gusto for the world of sports, this mantra from the 1989 baseball fantasy film Field Of Dreams is altogether apropos when describing the genesis of the Tedeschi Trucks Band and their debut recording at Swamp Raga.

Back when she was growing up outside Boston, Susan Tedeschi attended a basketball camp run by former Celtics center Dave Cowens. She is

still a tenacious defender when drawn into the “musicians ball” games that the group occasionally initiates on the road. (“We only play with other musicians and we try not to hurt ourselves,” Trucks explains. “Rebounding is 20 percent less aggressive and if somebody beats you, you let them finish it.”)

During an Allman Brothers Band summer tour in the early 2000s, the musicians and crew took a detour one afternoon to local batting cages. With the pitching machine set to fast, Tedeschi was the only one to make contact with every pitch. “I’ve got good hand-eye coordination but I’m not a power hitter—I’m more like an Ichiro [Suzuki, who celebrated his 4,000th professional hit in 2013].”

In July 2008, while touring with the Derek Trucks & Susan Tedeschi Soul Stew Revival, the pair traveled with enough people to field two full-on baseball teams. “We bought a bunch of gear,” Trucks recalls. “So on days off, we’d load up the bus, go to a field and play nine on nine.”

Soul Stew was the collective project that served as the precursor to Tedeschi Trucks Band. It drew together members of the couple’s respective touring groups. On one hand, it was an attempt by the family to be together while the couple’s son Charlie and his younger sister Sophia were out of school during summer vacation. Beyond that, Trucks acknowledges, “In the back of my mind, it was an unspoken audition for us— to see if it made sense, if we enjoyed it, if it was something we wanted to do.”

Ultimately, they decided it was indeed something that they wished to pursue but rather than continue Soul Stew, they aspired to form something new. While contemplating their approach, the pair looked to such antecedents as Delaney & Bonnie, James Brown and Bobby “Blue” Bland. Another turning point was a viewing of Mad Dogs & Englishmen, which inspired them to contemplate a horn section. The logistics of managing so many personalities and musical elements gave the pair pause, but then, on New Year’s Eve 2008, the Sun Ra Arkestra opened for Soul Stew at the Fox Theatre in Atlanta.

“I remember seeing these guys pushing their 70s and 80s, rolling up in a 15-passenger Ford Econoline to the show and I was like, ‘Wow, that is hardcore.’ Those guys were an inspiration, having the balls to even do it,” Trucks discloses. “Then, if you think about the big bands, those guys did it in cars, trains, and they did it for no money, especially later on. Early on, it was popular music but toward the end, it was not. It was for the love of the game.”

Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks cast conventional economic wisdom aside in selecting their new band. The couple enlisted two drummers, two backing vocalists and a three-piece horn section, with the complete group topping out at 11 players. This was the collective they decided to bring on tour in the midst of an economic recession, trusting their creative vision and enthusiasm to hold sway with audiences.

“I remember when we first started talking about it, our management asked us if we were thinking clearly,” Trucks chuckles. “I get it, I can do math. Then, there were other people we knew who were convinced that we were selling out by doing it. I was like, ‘I don’t think you’ve thought this argument through very well because we are playing the same venues with twice as many people onstage.’”

“It’s an unwieldy beast,” Mike Mattison attests. “There are a lot of personalities, musically and otherwise. It’s never easy having a group of musicians together. Musicians, for the most part, are idiot savants. They’re not the most well-adjusted people on earth, so to have 11 of them together is pretty ambitious from a practical point of view.”

One of Derek and Susan’s early decisions was to create a role for Mattison, who had been the lead singer in The Derek Trucks Band. She explains, “Mike is really one of my favorite singers doing it out there today. He’s a great talent and right on the same page with Derek and myself. It’s hard to have two lead vocalists, but he was really into the idea of doing the Gladys Knight & the Pips kind of thing—having the guys back up the girl. That’s not real popular. You usually have girls backing up a guy or girls backing up a girl.” While Ryan Shaw initially joined Mattison, after some scheduling conflicts arose, Shaw recommended Mark Rivers, who became Mattison’s fellow Pip.

Just as the background vocalists started with Mattison, the horn section began with Kebbi Williams, the man who Tedeschi describes as “the Jimi Hendrix of the tenor saxophone.” Trucks offers, “He’s such a free spirit, personally and musically. He is just one of the guys where you never know what is going to happen. Every time he picks up an instrument, every time he takes a solo, it can go in any direction; there is no preconceived notion. We were playing the Montreux Jazz Festival, and I was walking down the street when I heard this avant-garde trombone. It was Kebbi playing some other dude’s trombone. He’ll grab any instrument at any time. He just does not care. He’s fearless. There’s something to that.”

There’s something else to Williams as well, which Tedeschi notes, with deep admiration. “He lives in a pretty rough neighborhood in Atlanta and sees a lot of these kids struggling to eat. So what does he do? He goes to a bank on an off day on tour and gets a $15,000 loan to buy a little piece of land in their neighborhood and start a community garden. He did this for his neighborhood kids so they could eat organic and take pride in growing it themselves. Kebbi is the real deal.”

By the time the band convened at Swamp Raga in late 2010 to record Revelator, Maurice Brown (trumpet) and Saunders Sermons (trombone) joined the brass section. The drumming tandem of Tyler “Falcon” Greenwell and J.J. Johnson, along with the Burbridge brothers, Oteil (bass) and Kofi (keyboards/flute), completed the lineup. “Everybody was getting their sea legs in terms of how this was going to work technically, getting used to the studio space and just figuring out how to be in that environment,” Mattison recounts. “There’s a studio out there but there’s also their home and when you get 15, 16 people milling around, there aren’t many places to go, so you’re kind of in somebody’s house. I think it’s a testament to Derek and Susan that everybody felt at home. It’s not like, ‘Hey, you guys are crossing a line,’ or ‘We need some private time.’ It could get a little cramped but everybody was welcome in every sense of the word.”

Trucks produced the album with Jim Scott, and Derek approached the sessions with a particular objective regarding Susan. “One of the reasons I wanted to put this band together and do a record is I think she’s one of the great singers of this generation,” Trucks contends. “And I felt like whenever that conversation came up, for some reason, she wasn’t in it—maybe because it’s easy to get pigeon- holed in a blues rocker thing but there’s just so much more to it than that. I feel there are a handful of timeless songs that her voice deserves. We’re still trying to write songs for that. ‘Midnight In Harlem’ is a great example of a timeless song and a timeless voice and those things don’t happen much anymore.”

While Revelator would go on to win the Grammy for Best Blues Album eight months after its June 2011 release, it took a little while for Tedeschi Trucks Band to gain momentum. This was partially by design, given the bandleaders’ particular commitment to artistic integrity and an unwillingness to pander, almost to a fault. In an effort to allow the new group to flourish on its own terms, they pushed away from familiar back-catalog material, fearing that audiences would view TTB as a brief, indulgent interlude before its namesakes resumed their prior projects and that this might impact the music in some way.

“Although they might not admit it,” Trucks elaborates, “every musician, every band, finds certain things that work, whether you’re inspired or not or whether you’re having a great night or not. There are certain songs that people will respond to; there are certain grooves and solo sections where you can get a crowd to roar every time. We didn’t want any safe bets, any cheap shots—we really wanted to do it new and fresh, finding different ways to make it happen.”

Part of Derek’s approach has been to keep the band on its collective toes, as with a nod of his head, he might call an audible assigning one of his regular solos to another member of the group. This tactic has been met with resounding success even if it has occasionally flustered one member of the TTB.

“Derek and Falcon sometimes push my buttons to get me mad,” Susan acknowledges, citing a night when her husband was trying to get her to solo on “Get What You Deserve,” where he typically takes the honors. “I was like, ‘No, I am not playing on it; you play on it.’ I was being bratty and he just sat there and wouldn’t play.”

Derek affirms, “I was like, ‘I will wait you out. We will all just stand up here mid-tune.’ I told her, ‘You can pout but you better play.’” “They were right,” she now laughs. “I was pouty and bratty about it that night, and I was like, ‘Grrrrrr.’ Afterward, they told me, ‘Yay, Sue, awesome solo,’ I was like, ‘Shut up.’”

Her husband acknowledges, “It was a great solo. There are certain songs that I know that if she’s a little mad, she’ll play better guitar—she just takes it out on the guitar. So there are times that I’ll needle her a little bit onstage right before a solo and Falcon will look back at me and say, “Yeah!” He’s known her long enough; he’s played in her band. He knows that when she’s in certain moods, she’ll play better. When you have family that’s this tight musically, where you can do stuff like that, people will laugh about it when it’s over. It’s never mean-spirited. We never go too far.”

Still, while it’s one thing to playfully antagonize a co-worker, things could become a bit more complicated when that person is one’s spouse. There are many loving couples who would find the experience of working together on a daily basis while sharing a leadership role to be somewhat trying.

“We usually paint a pretty picture,” Susan offers, “but it’s not perfect all of the time. It’s hard. Derek’s used to being a leader and having things flow smoothly. I’m sort of like a big stick in the wheel and he has to deal with me on top of it. I have to deal with him. We’ve been really lucky that we’ve been able to communicate.”

“I can honestly say that our relationship has been better since we’ve been doing this,” Derek asserts. “When I think about it, it’s always in context. Relationships are work but it’s been so much better doing this together because we’re doing something we love to do. It’s like raising good kids. When your kids do something you’re proud of, it makes you feel better about each other. Plus, for us, it hasn’t been like we were ever home together, hanging out and having a normal life. One of the reasons we waited this long to do it was to make sure we knew each other well enough and had matured as people enough. That’s what the Soul Stew thing was a little bit—trying to feel that out. I think one of the things we’ve been really good about is—other than needling each other—we don’t bring it to the stage. When we hit the stage, all bets are off, no matter what we’re going through. We have enough respect for the band and for the work we’re doing. We hold ourselves to a high standard. Even if we’re going through some shit, it doesn’t hit the stage.”

“We’ll actually talk about it,” Susan affirms, “and say, ‘OK, whatever we’re dealing with, we’ll talk about it later.’”

“Talk to you in four hours,” her husband adds. “I’ll meet you in room 417.”

“Which is good,” she continues, “because it gives us some time to think about it. And playing is the best healing anyway. If you have something that is frustrating you, there’s no better way to let it out than music.”

The nine-minute version of “Midnight In Harlem” that Tedeschi Trucks Band performed on the afternoon of Sunday, September 8, 2013 at Virginia’s Lockn’ Festival was sublime. Derek sounded the call at the outset with a shimmering, yearning solo. The audience then offered a hearty applause of recognition as Kofi Burbridge’s familiar organ lines spelled out the Revelator tune. It was one of many songs that received such a response at the festival on what served as family reunion day for the TTB.

Among the musicians guesting with the group was Oteil Burbridge, who a year earlier, had announced that he would be leaving Tedeschi Trucks Band to focus on starting a family with his wife Jessica. That decision was not altogether unexpected.

Derek explains, “When we first talked about putting a band together with Oteil, he was a little road-worn but the chance for all of us to work together was too much to pass up. From the beginning, I knew it wouldn’t be a 20-year thing with Oteil, or 15, 10 or even five but the chemistry out of the gate was so strong that we just did it. But when you’re trying to start a young family, not everyone’s OK with you being gone all the time. Our band is so big that not everyone is privy to every conversation. Not everyone knew Oteil’s backstory and it was hard for everyone to make sense of it all, especially when things were rolling so well.”

To keep things in motion, the group opted to record Made Up Mind, the rich, soulful follow-up to Revelator, with multiple bass players. This decision proved conducive to the material as contributions by Pino Palladino, Bakithi Kumalo, George Reiff and Dave Monsey added variety and nuance to the recording. Jim Scott returned to Swamp Raga to share production duties with Trucks, and the result sounded both timeless and of the moment.

The following eight months saw a variety of bassists on something of a catch-as-catch-can basis with the group, including Palladino, George Porter Jr. and longtime friend Eric Krasno, who moved from his familiar role on guitar. However, this period began to take its toll on the band, as the musicians essentially needed to relearn the material for each new bass player.

By Lockn’, this era had just ended with the addition of Tim Lefebvre, who finally liberated the group from its Groundhog Day cycle. Lefebvre—who had recorded and performed with Wayne Krantz, Bill Evans and Mark Giuliana—first raised eyebrows during his initial rehearsal with the group and by the second night of the TTB’s late summer tour had won them over, leading Kebbi Williams to observe, “I feel like the band formed again.”

Tedeschi has high praise for everyone who filled the bass role, noting that each player highlighted the group’s many hues. However, she also observes that Lefebvre propelled the group in a singular manner: “The energy really changed with him. My brother Jamie, who used to play bass, had a really good description of Tim. He said, ‘Sue, this is the first bass player I’ve seen play with you guys that has driven the band.’”

“He’s coming from a place that I’m not fully aware of, which is nice,” Trucks adds. “It’s fresh music, fresh ideas, fresh blood. The fact that a lot of us haven’t played with him and don’t know him is kind of exciting. He’s unafraid, progressive and he approaches things differently than I have ever approached them. I never really played with someone that has the angle he has.”

With Lefebvre firmly in place at Lockn’, the TTB concluded their set with a double dose of Sly & the Family Stone, moving from “Sing a Simple Song” into “I Want to Take You Higher.” As they slid into the second tune, unbeknownst to the musicians up front, Bob Weir, Chris Robinson and Jackie Greene joined the formation at the rear of the stage, wielding tambourines and singing harmonies. After discovering the trio, Susan beckoned Weir to the front and he ambled up to her mic, joining the explosive fray.

One of the remarkable things about the Tedeschi-Trucks union is that Derek isn’t the only one to have earned his Grateful Dead bona fides. In 2002, Susan Tedeschi embarked on a fall run with The Other Ones [soon to be redubbed The Dead]. “Being out with Bobby, I quickly came to realize how quirky and original his thing is. He plays some really intricate rhythm parts and does some really cool things that you don’t necessarily notice. And he’s just a sweetheart. He’s absolutely down to earth and sweet as pie. Phil, too—they’re really just loving guys.”

Tedeschi and her group maintain a similar collective sentiment for Chris Robinson and The Black Crowes, who had invited TTB to share a bill and then the stage throughout a summer tour that concluded three weeks earlier. (The Crowes’ lineup now includes Greene, who once opened a few tours for Tedeschi.)

Robinson indicates that a communal spirit took hold from the start. “Day one up there in Nashville, it was like, ‘Should we jam?’ ‘Yeah, what do you guys want to do?’ So it was everyone in the pool right away and it just took off from there.”

Where it ultimately landed, beyond steady sit-ins over a month of shows, was a climactic final evening outside of Detroit in which 20 musicians—both groups along with the openers London Souls—packed the stage for a six-song encore.

The collaborative sequences led Tedeschi Trucks Band to learn new songs daily at the beginning of the tour. This effort, in conjunction with the infusion of energy that Lefebvre brought to bear, proved liberating to Derek in particular, who was willing to break from his group’s more regimented recent past to suggest, “Let’s throw in a new song tonight and if it tanks, we’ve got 12 others.”

Chris Robinson was on hand to watch all of this develop from a steady perch at the rear of the stage. Mike Mattison still marvels at the fact that the Crowes frontman would seemingly forgo dinner to watch many of their sets throughout the tour. “Mark and I would be back there and the first song would end, there would be some applause and I would turn around, and there was Chris on a drum case going, ‘Do that shit! Do all that shit! Do it!’ He was just enjoying himself and it was really fun.”

That kind of infectious energy emanated from both sides of the stage in late September over three evenings at New York’s Beacon Theatre. Each show took on its own character, reflecting the band’s versatility and aplomb. Night one showcased the group’s freer more exploratory side. The concluding performance had much more of classic soul feel with special guests Lee Fields, Doyle Bramhall, Neal Evans and Eric Krasno. Still, it was the middle gig that many cherish, as the group brought Dickey Betts back to the stage—where he had once performed so many dates with The Allman Brothers Band—for “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” “Blue Sky” and “The Sky Is Crying.”

“I’ve seen a lot of moments at the Beacon,” Trucks reflects. “I think I’ve been there for 170 shows and that one had a unique feel because it was pretty unexpected. When Clapton played with the Allman Brothers, everyone already knew—the word had gotten out. It was still an amazing moment when he stepped out onstage, however, it wasn’t a shock. But when Dickey came out, you could tell it meant something. The thing I enjoyed about it is that it wasn’t lost on anybody. It was some sort of bridge, some kind of minor healing to the whole saga. That, to me, was the point of it.”

The decision for Tedeschi Trucks Band to perform Allman Brothers Band material also says something about the development of the TTB. Where Derek was once adamant about circumscribing the group’s repertoire, he was now prepared to cast aside these earlier dictates.

“We’re at a point where we feel like we’re established enough that we can play whatever we want to play. If we want to do a song from Susan’s record, we’ll do it without thinking about it. If we want to do a song from one of my old records that Mike sings on, we’ll just do it. We’re not worried about confusing anyone with what this is anymore. I think, as time goes on, the parameters get wider and the lid comes off.”

Chris Robinson, who has had a hand in this development and certainly observed it from a unique vantage point, is over the moon about the group’s future.

“In a world of contrived, corporate, shallow status-seeking nothingness, there’s a whole lot of love right there—and a whole lot of organic music and a whole lot of cosmic consciousness. I couldn’t be more impressed. I don’t know where excellence begins and tremendous stops. It’s all one big scoop of joy.”