Tame Impala’s Eclectic ‘Currents’

Kevin Parker is only a few bites into a leisurely Monday breakfast when he drops his first F-bomb of the morning. “Fleetwood Mac,” he says with a slight grin when asked about the genesis of Tame Impala’s surprisingly polished and refreshingly groove- centric third album, Currents. “I heard one of their songs, and it was just so pure, clean and throbbing at the same time. I wanted to see if I could make a song where I didn’t just fill every little crevice with a sound effect or drum fill.”

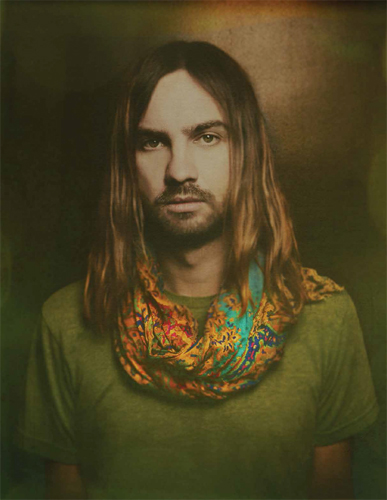

The thin, longhaired 29-year-old Australian singer, guitarist and overall Tame Impala mastermind is sitting in an old-school West Hollywood, Calif., diner just hours after the final encore of Coachella’s first weekend and, from the radio shock jocks talking about their pool-party interviews to the dazed teenagers liking those posts on Instagram, the entire city seems to be nursing a post-festival hangover. In certain ways, all of Los Angeles is on an extended set break until Coachella picks up with an identical lineup four days later—and everyone with a horse in the game is placing bets on the fest’s big winners.

One surprising current is already apparent: The gap between posh celebrity culture and heady psychedelic space continues to shrink with the economic punch of a tabloid headline. There are whispers that recent LA transplant Beyoncé hung with Philadelphia indie-darlings The War on Drugs, whose Tom-Petty-drenched brand of psych-rock could be considered something of Tame Impala’s cosmic cousin. A few days later, photos of John Mayer hanging out with the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir surfaced on various social media platforms. As the trend merry-go-round circles closer to the Summer of Love’s 50th anniversary, it’s clear that psychedelic music hasn’t been this hip since the Age of Aquarius came to a screeching halt in the early 1970s.

Though Parker has openly declared his love of Britney Spears and boasts that he’s never put a Pink Floyd album on in his life, Tame Impala are unquestionably at the center of the modern psych-rock boom. Not only have they singlehandedly introduced the international music community to fellow Perth-based acts like Pond, but several media outlets have also even described Tame Impala as their generation’s Beatles.

It makes sense, too. While Tame Impala weren’t the first hipster outfit to revisit the mind-expanding, garage-rock sounds of the ‘60s in the 21st century, they possess both the raw talent and charismatic charm to serve as the poster children of psych-rock, a modern strain that fuses indie’s raw bite and jambandia’s blissful expansiveness into a scene of its own. Parker’s angelic, space-age croon even recalls John Lennon’s vocal range during The Beatles’ own art-rock period. But after turning in two full-length albums of Nuggets-worthy crunch, Parker decided to shift gears with Currents.

At Coachella, Tame Impala showcased the two Currents songs that most of the world has heard—the groovy, R&B-flavored slow jam “‘Cause I’m a Man” and the eight-minute keyboard kraut- rocker “Let It Happen.” A sharp turn from Tame Impala’s trademark sound, Parker pushes his electric guitar to the side on the former track and puts down his axe completely on the latter song.

“I just wanted to have something you could turn up really loud and it would still be pleasing to the ear,” Parker says, pecking away at his breakfast of avocado toast and a Corona. “Tame never gets played in clubs at large volumes. I love the wall of sound, but I also love it when you feel a song in your chest before it’s screaming in your ears. I wanted to make an album that hits you in the chest.”

Parker and the rest of Tame Impala’s live band are holed up for the week at an almost-refurbished hotel attached to the diner that feels somewhere between charmingly retro and downright dingy. The open-air pool positioned in the center of the courtyard is under construction and the chainsaws chipping away at the building’s Bates-Motel-like crust are an audible sign that change may in fact cut through the wall at any moment. Though Parker has a reputation for being an introverted, bedroom-recording artist, he’s in great spirits and clearly enjoying his time in the LA spotlight. His cheeks are bright red from the Palm Springs sun, and his still-visible Coachella artist bracelet completes his tight black- shirt-and-scarf ensemble. As he sees it, perhaps the only downside to Tame Impala’s marquee set before headliners AC/DC is that the better billing has restricted his ability to see other bands.

“I’m quite particular about the first time people hear a song,” he says of his decision to keep the rest of the album’s tracks close to the vest. “I want them to hear the version I spent two years on, not the version we bashed out live when we were half-drunk. The thought of someone capturing a song through a mobile phone and sticking it on YouTube horrifies me.”

Kevin Parker was already immersed in Perth, Australia’s local underground music scene by the time he started Tame Impala in 2007. The son of a part-time musician who taught his family the virtues of melody through his Beatles and Beach Boys covers, Parker was fascinated by music from a young age. His early interests ranged from Michael Jackson to rap- metal, and he showed promise as a drummer. Along with some friends, he formed the Dee Dee Dums in 2005, a Cream-inspired outfit that served as Tame’s most direct precursor.

Though he didn’t admit it until recently, Parker conceived Tame Impala as a solo mouthpiece. “I was too shy back in the day—I would never have the courage to have a pseudonym like Caribou,” Parker says of his initial decision to present Tame Impala as a proper group. “I never considered myself an artist. I had to hide behind four other guys to gather the courage to put my music out there. It got to the point of lying and saying that it was us that recorded it. For so many years, I said, ‘Me and my band—we recorded this album.’ It’s been a complete lie for a long time, but it came from not wanting to stand next to my music—just me, alone.”

Adding to the mystery, Parker put together a steady Tame Impala live band featuring his closest creative partners, bassist Dominic Simper—a fellow Dee Dee Dums alum—and fan-turned- drummer Jay Watson. Soon after, guitarist Nick Allbrook joined the group’s touring ranks, and eventually switched instruments with Simper.

“We were totally those pot-smoking dropouts, listening to Jefferson Airplane and The Doors,” Parker fondly reflects of Tame’s early days while fidgeting with a straw wrapper and mindlessly organizing his utensils after his meal. “The Doors had a big impact on me when I was 22-23—those stretches of time where their music was totally unpremeditated.”

Australian indie label Modular Recordings heard Parker’s music through MySpace and nabbed Tame Impala while he was still massaging his space-age, indie-rock sound. Parker released a series of well-received Tame Impala EPs in 2008 and 2009 and scored international recognition, thanks to guitar-driven Mod nuggets like “Half Full Glass of Wine” and “Sundown Syndrome,” which landed in the Oscar film-nominated film The Kids Are All Right.

“They were an amazing live band, even before they’d really done a bunch of touring,” says MGMT’s Ben Goldwasser, an early champion who brought them on the road. “We have a lot of the same influences. We bonded right away.”

Tame Impala caused a hipster frenzy during their first visit to the States in 2009 and, much like Seattle after Nirvana in the 1990s, labels, agents and journalists almost immediately started scouring Perth for the next great psychedelic act. That search shed some light on Pond, a harder-edged brother band that includes Watson, Allbrook and other Tame family members. (“Pond does all of the naughty things that Tame Impala wouldn’t do,” Goldwasser says of the group, who some consider the Stones to Tame Impala’s Beatles.)

“It’s about 15 people, who make up about seven bands,” Parker clarifies. “It’s not really a ‘psychedelic scene.’”

Parker also released a proper full-length, Innerspeaker, which he recorded while camped out in a beach community about four hours outside Perth. Watson and Simper left their fingerprints on the sessions, and Dave Fridmann—who has helped bands like MGMT and The Flaming Lips make traditionally weird sounds feel sexy—was eventually brought in to mix the sessions, but Parker made the album almost entirely on his own.

The psych scene’s shot heard around the world, the record boasted standout, supercharged stoner-rock tracks like “Lucidity,” “Why Won’t You Make Up Your Mind?” “Solitude Is Bliss” and “Expectation”—and introduced a new, blog generation raised on garage rock to a kaleidoscope of heavy, ‘60s-drenched sounds.

Parker followed Innerspeaker with Lonerism, a denser, more experimental, art-rock record that married his newfound reliance on electronic music and ambient sounds with his increased interest in pop. He utilized numerous synths and cites Todd Rundgren as a direct influence on the sessions. Once again, Parker recorded most of the album on his own—this time, while on tour— with some minimal help from Watson. (Fridmann returned to sweeten the mix, too.)

“When Lonerism came out, I didn’t expect anyone to say it was psychedelic,” Parker says. “In fact, I was feeling a bit guilty for the psychedelic Deadheads. Turns out, it was the most psychedelic album I’ve made.”

Watson, who in a rare move co-wrote a few songs on Lonerism, developed into Parker’s first responder. “Jay is very direct with his criticism—he’ll give you the real deal,” Parker says. “I felt really paranoid about Lonerism before I brought it out. I’m always insecure about my albums, so I played him Lonerism, and he told me it sounded like a big mess of drum fills and flanger. He couldn’t pick any melodies.”

However, there were melodies buried in those left-leaning recordings, and Lonerism spawned several popular singles in 2012 and 2013: the marching psych-ramp “Elephant,” the dreamy anti-ballad “Feels Like We Only Go Backwards” and the spiraling pop-odyssey “Mind Mischief.” It also propelled Tame Impala into large clubs and choice festival spots around the world.

As Tame Impala’s popularity increased, Parker gradually grew more confident talking about his interests and ambitions. He formed a close bond with Wayne Coyne, appeared on the guest-heavy 2012 album The Flaming Lips and Heady Fwends and followed up that collaboration with an EP where The Flaming Lips and Tame Impala swapped covers. (“A dream come true,” he gushes.)

After name-dropping Spears and Kylie Minogue in various publications, Parker inched closer to the mainstream world by working with producer Mark Ronson on his 2015 banger, Uptown Special, joining an A-list cast that included Stevie Wonder, Bruno Mars and Jeff Bhasker. Parker says the idea stemmed from a drunken con- versation they had at a mutual friend’s party in London. “I said ‘Mark, do you wanna make a funk album?’” Parker recalls with a clear grin. “And he said, ‘You had me at: Do you wanna.’” (The singer makes a point to mention that he admires Ronson’s production abilities as well as his clothing style and swagger.)

Soon after, Parker found himself in a professional recording studio for one of the first times, laying down smooth tracks with members of The Dap-Kings and other studio aces. “I’m into a lot of different types of music and if I’m doing one thing for too long, I try to concentrate on something else,” he says, noting that he also had his own funk side-project. “I look at it as all these different spit valves I use to release the saliva.”

Shortly after finishing Lonerism, Parker had a profound revelation. “I’ve always loved pop, especially ‘90s R&B,” he admits. “Even when I hated it categorically, because I was supposed to, I still secretly loved these TLC and Jennifer Lopez songs. They were guilty pleasures, but when I grew up, I realized there’s no such thing as a guilty pleasure. Then the world of music opened up to me—it wasn’t like I was staring down this tunnel vision.”

Though some of the biggest bands of the ‘60s and ‘70s released psychedelic opuses, by the dawn of the 21st-century, pop had turned into a dirty word, thanks to decades of boy bands and big, bloated labels. But during the past decade, as genre boundaries have blurred in a world of MP3s and ever- eclectic festivals, those harsh lines have started to fade and a new, fashion-forward world of celeb-jammers has emerged.

“People talk about opening their mind to psychedelia—and I love psychedelia—but I don’t think it’s opening your mind if you shut out everything else,” he says. “Being in the music industry, you see it in a different light, too. You have these preconceptions when you’re a kid that pop music is fake and everyone involved is in it just for money, and that everyone that plays rock music is keeping it real. In the last two years, I’ve met bands that are meant to be super down-to- earth and they’re just absolute dicks; they’re just completely self-centered. And you meet a pop artist, and they’re just really down-to-earth.”

Parker says he’s always toying with song ideas and, in a sense, started working on Currents as soon as he finished Lonerism. Fleetwood Mac were an early rallying point: Though, for many years, the ‘70s superstars seemed to represent pop-rock’s Behind The Music excess, in recent years, a new generation of indie-rock musicians has come to embrace both the universal appeal of their broad, rhythmic hits and their ability to subtly mask art-rock in pop hooks. He also reached back to his first love.

“In primary school, I would just walk around the oval, pretending to be Michael Jackson in the ‘Black Or White’ clip,” he says with a smirk. “I shut him out as an artist when I got into grunge, thinking it was too soft. But recently, I started to realize how inspirational his music can be.”

Parker worked on Currents in the same coastal house he used to record Innerspeaker, but he returned a changed man. He’s in a stable relationship and recently bought a house and built a home studio to work on ideas. “Currents’ sound is half dictated by the music, half dictated by my own feelings and perceptions of where I’m going as a person,” he says softly. More important, he was finally confident with his singular vision for Tame Impala’s next step. In fact, he describes Currents as one of the most insular albums he’s ever recorded. “There was virtually no one involved until mastering,” he says confidently. “I even mixed it myself this time, which is a big step for me. I’m a producer, and just realizing that gave me a sense of confidence, like maybe I do have a good ear for styles? I started off assuming that I was nothing, and just made music for myself and maybe some friends. Step one of building self-confidence was a record label saying, ‘Hey, you wanna sign with us?’”

Parker originally worried that the record was too sonically schizophrenic; it jumps from the soul of “Yes I’m Changing” and the bass-heavy beat of “Less I Know the Better” to the synth-pop mysticism of “Eventually” and the old-school, Tame Impala bounce of “Reality In Motion.” But he eventually realized that his voice and stories add up to an “overall mood and perspective within the music.” Currents arrives at a time when everyone from the Alabama Shakes and My Morning Jacket to D’Angelo are toying with a similar 3-D sound that meshes psychedelia and R&B in a way that would make Marvin Gaye proud. The band’s new direction has caused Parker to reconsider Tame Impala’s musical identity in light of his own artistic ambitions. In the future, he’s ready to release other styles of music that he may have previously reserved for side projects under the Tame banner and, though he will likely continue recording by himself for the time being, he sees the appeal of bringing a band into the studio.

“The more I embrace everything I want to do, rather than what I think is right, the harder it gets to draw the line,” he says, glancing through the diner’s window. “The challenge is honing it in and making it co- hesive. I’m getting a clearer perspective on what I’m doing, hence being a good producer. But I’ve never been as fucking crazy—like I’mgoingasinsane—asIwaswiththisalbum. Recording it by myself, I felt myself slowly falling off the edge. Finishing this album was the first time I realized why people become alcoholics—all of those times where I felt like I want to disappear into oblivion.”

Parker has also tweaked Tame Impala’s live show to include interactive components and trippy visuals. In 2013, Allbrook left the Tame Impala touring band to focus on his solo project and Pond; Parker has since expanded his backing group to include two additional players and an arsenal of instruments and effects. At times, Currents’ arrangements require the live musicians to pick up new instruments or even play two instruments at once. Yet the band’s powerful show is still the type of immersive live experience perfected by psychedelic warriors from the Grateful Dead to Animal Collective. “The more adventurous I am in the studio, the more of a challenge it is in the rehearsal room. There used to be a bit of improvisation in our live show, but it’s been slowly weeded out as we’ve added more production and visuals to the Tame Impala live experience. It seems like a waste to do a 10-minute jam, but the Tame Impala live band is all about an unspoken connection,” Parker says. “It’s kind of like in Power Rangers when they all combine to become that Megazord.”

But no matter how successful Tame Impala have become, or who Parker has rubbed elbows with, hints of that insecure bedroom- artist remain. “Even when I make an uplifting song, it’s never 100 percent uplifting because I just can’t do that,” he admits. “It’s always got a darker edge. People will read the lyrics and say, ‘This is some introspective shit.’” He also struggles with his own developing legacy. “Innerspeaker and Lonerism are still tainted with self-critique when I listen back to them,” he says. “It’s still impossible to just appreciate them. I’ll never truly be able to listen to those records for the first time, which is kind of a bummer. But at the same time, I should just get over it—and get over myself.”