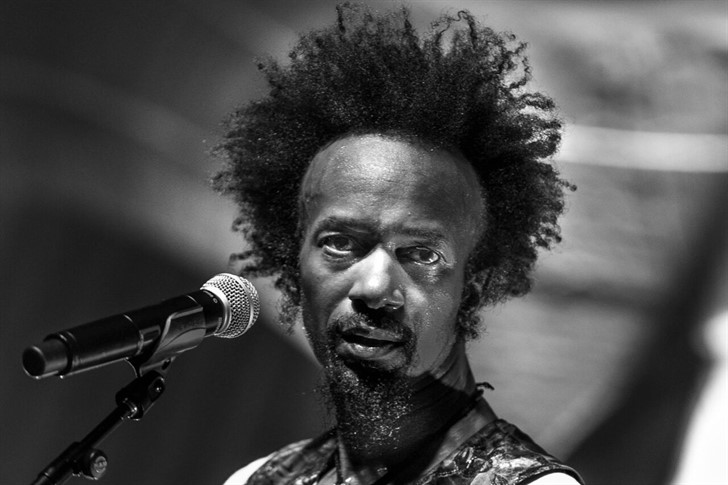

Spotlight: Fantastic Negrito

Alberto Bravo

Alberto Bravo

It is no secret that America is in the middle of a cultural upheaval—and when that happens, artists tend to be among the first to give the clash of attitudes a provocative voice. Just scroll back through Beyoncé’s career-defining statement at Coachella, or even more recently, Childish Gambino’s sticky, complex video for “This Is America,” which rolls up the ugly legacies of slavery, police brutality, mass shootings and mass incarceration into a tightly choreographed tableau of protest.

Xavier Dphrepaulezz (that’s “dee-FREP-ah-lez”) is intimately familiar with the stance. The son of a Somali-Carribean immigrant, he grew up in Massachusetts before moving to Oakland at age 12. Almost immediately, he left home for the hard-knock life of the streets, ending up in foster care with a strict but loving Christian family, while he obsessed over hip-hop and taught himself piano by posing as a UC Berkeley student so he could sneak into the campus practice rooms.

“I’m willing to be all kinds of people and take all kinds of chances,” Dphrepaulezz says from his farm—a small plot of land in Oakland, Calif., where he raises chickens, grows various crops (including cannabis), and welcomes friends and their families on weekends to till the soil. “But one of the beautiful things about being a middle-aged guy just breaking as a musician is you get to do what you want. I don’t want to be famous with the big pop record so, as a producer, when I go into the studio, I try to separate myself. Some people call it a personality disorder, but I wanted the artist Fantastic Negrito to do something else. I wanted him to say something else.”

He’s referring to his latest album Please Don’t Be Dead, recorded under the name he gave himself a few years ago, when he reemerged from a long hiatus away from music. The quick and brutal history: Back in the early ‘90s, after learning to play every instrument he could find, a near-death mugging prompted Dphrepaulezz to move to LA, where he tracked his first demo. By 1994, he signed to Interscope as Xavier and, a few years later, he released The X Factor, a Prince-influenced slab of earnestly futuristic R&B that sank like a stone. Then in 2000, a car crash put him in a coma for three weeks, disfiguring his guitar-playing hand and breaking much of his body, which set him on the long, hard road of physical therapy and recovery.

Please Don’t Be Dead is the follow-up to 2016’s The Last Days of Oakland, the first album that Dphrepaulezz recorded after the accident, and a critical success that scored him the Grammy for Best Contemporary Blues Album. Along the way, he won the 2015 NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert Contest and his viral street-busking videos piqued the interest of the late Soundgarden frontman Chris Cornell, who brought Fantastic Negrito on board as the opening act for his 2016 Higher Truth tour. “At that point, I started nicknaming him Christmas Cornell,” Dphrepaulezz says reverently, “because man, every time the guy called me, it was really good news. He was just an incredible human being.”

Gratitude, respect, hope and an unwavering idealism fuel the music on Please Don’t Be Dead—a rootsy and resplendent garden of blues, rock, funk, hip-hop and even East African influences that draws most of its narrative weight from the American dream-turned-nightmare. On the uncanny “Plastic Hamburgers,” Dphrepaulezz sounds inhabited by a young Robert Plant, belting out lyrics like, “Automatic weapon in a twitching hand/ the 50-foot wall of addiction man” with a fervor that matches the “Helter Skelter”-meets-“American Woman” sonic rage laid down by his longtime backing band. It’s just the opening salvo on an album that soars and dips with moments of bluesy menace (“Bad Guy Necessity”), righteously chilling shamanism (“A Boy Named Andrew”), soulful transcendence (“Never Give Up”) and funky, uplifting humor (“Bullshit Anthem”). No matter what style he’s exploring, there’s always a nod to the Delta masters—like Son House, Robert Johnson, Skip James, R.L. Burnside—who inspired Dphrepaulezz when he came back to music making.

“Everything comes from the blues in this country,” he says. “I really fell in love with music again when I was listening to all these amazing musicians because it was so punk rock, in a way. It was so revolutionary and American. Here these guys were, the whole world is stepping on your neck and telling you you’re not even a human being. You’re not even a man. Well, hell, go sit down with a guitar and become a genius. That’s American, you know what I mean? It’s like, ‘We got this, motherfucker.’”

He’s quick to point out that there’s something in the music for everyone, which is why he finds strength in the “power of the riff. That’s universal. It’s the chant, the thing that grabs us and unites all of us. We gotta do the music that unites us, no matter what side of the spectrum we’re on. Let’s bring back the middle ground—and real courtesy—and sit down together although we disagree.”

From the biting lilt of “Transgender Biscuits” (with the incomparable Joi Gilliam on backing vocals) to the haunting ode “A Cold November Street,” Dphrepaulezz has tapped into an American zeitgeist that’s still evolving. Even as his own music has undergone a transformation toward an expansive sound that’s grittier, funkier and even a bit nastier, it is more imbued with positive energy than ever before. It’s also an ethos that defines the Blackball Universe, the artist collective, gallery and recording studio he co-founded with television writer Malcolm Spellman on Madison Street in Oakland’s Jack London district. “We will be moving,” he reveals, “because we’re from Oakland, and all artists—even if you’re a Grammy-winning artist—get evicted! But I’m very optimistic. I’m a guy with a hand that should never have played an instrument again, but here I am. I just believe whatever happens, we can see the good in it if we want. And that’s why I love the idea: ‘Take the bullshit and turn it into good shit.’ It started as a chant I would do at concerts, and it turned into a song. That’s how it is, man. Things change, and there’s nothing we can do but adapt.”

This article originally appears in the July/August 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.