Schrödinger’s Dead: The Grateful Dead’s 1975 Retirement

The first Grateful Dead show I learned inside and out (or so I thought) was the double-disc One from the Vault, two sets recorded on Aug. 13, 1975 at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco. Bill Graham introduces the band as the musicians click in one-by-one behind him. Jerry Garcia comes last as Graham’s introduction peaks, “Will you welcome please”—half-beat pause—“the Grateful Dead” and the band drops into “Help on the Way.”

It is, of course, the only time it happened like that. While it’s a truism to say that no two Grateful Dead shows were alike, it’s especially true of 1975, a year that only included four of them. But the Great American Music Hall gig was especially unlike any other Grateful Dead show in that it contained two sets of complex and mature new material buffed to a sci-fi chrome and performed in a 600-capacity room, smaller than the band had played in years. Returning to the recording and the rest of 1975 suggests another truism: It is impossible to listen to the same Grateful Dead show twice.

Once one starts exploring Grateful Dead live recordings, the tendency is to listen to more and more of them, each altering the context of the ones already heard. More than a band with a traditional catalog of studio work and outtakes, no matter how large, the Grateful Dead’s music is a renewable historical resource, changing constantly as new pieces of the past come to light. Even so, it’s possible that 1975 remains the most intriguing year in the band’s ever-intriguing history, filled with creative what ifs and choices that would define the band’s next two decades.

Coming into its 40th anniversary (and the Dead’s 50th), the available documentation pertaining to the band’s so-called “retirement” of 1975 has already been considerable. Besides Blues For Allah, the official product of the year, the ‘75 corpus includes the expected live tapes, a range of memoirs and a cache of rehearsal recordings made at Ace’s, Bob Weir’s new home studio between February and June. Featuring triangular porthole-like windows onto the sylvan side of Mount Tamalpais and a dangerous driveway with roadies loitering at its foot, Ace’s was the Dead’s own private treehouse for the year.

Down a connecting walkway from the studio into Weir’s living room, the band’s aide-de-camp Steve Brown manned a cassette deck, recording hours of studio jams that are singular in the band’s sprawling underground canon—some heard by now, many not. Filled with (in Brown’s words) “instrument tuning, storytelling, news of the day, conspiracy conjecturing and lots and lots of laughing and coughing,” the tapes are held together by the sound of a whole new Grateful Dead forming.

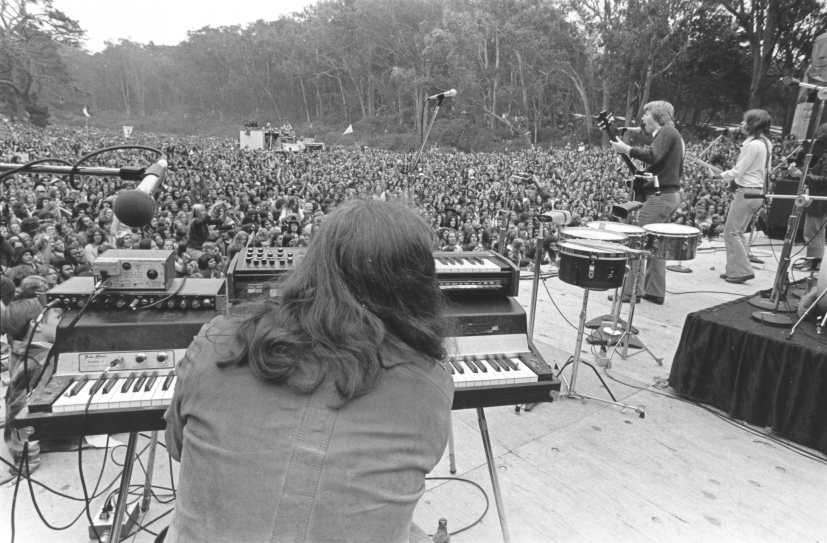

Inside Weir’s studio, sequestered away from the world, they are Schrödinger’s Dead, almost audibly unclear to even themselves if they really are still the band that left Winterland’s stage in October. Indeed, the first two shows of 1975—March 23 at Kezar Stadium in Golden Gate Park and June 17 at Winterland—were both benefits billed as Jerry Garcia and Friends.

Brown’s uncirculated tapes are the basis for one of several new perspectives on 1975 now available: a chapter in So Many Roads, the excellent and rich new Dead biography by Rolling Stone writer David Browne. “That year, ‘75, had always held such allure for me because of its mystery,” Browne said recently. “We all know they didn’t tour and only played a couple of shows that year, but what exactly was going on at Ace’s and how was the band dealing with the time off?

“I had access to a good chunk of raw, unfiltered tapes from those sessions—far more than what’s already floating around online—and I pored over and painstakingly transcribed each comment, conversation and wisecrack. To hear the guys yapping, joking, indulging, teasing each other and working out material from scratch provided enormous insight into their dynamics— they were still teasing Weir about his health-food regimen—and creative contributions.”

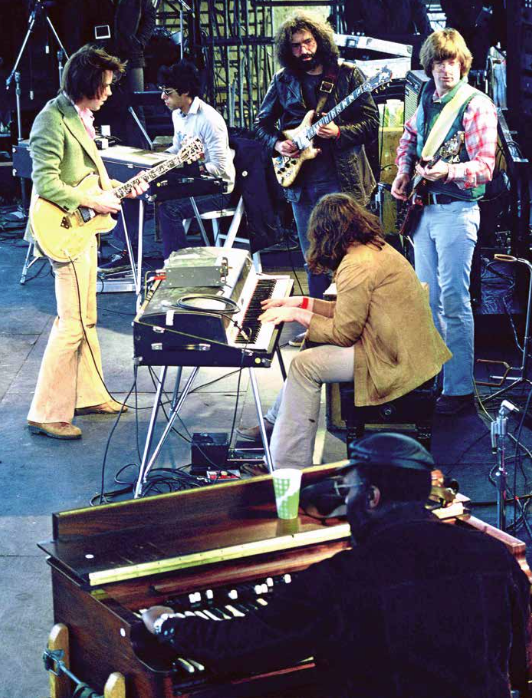

With well over a dozen hours currently spread between archive.org, box set bonus tracks, various Grateful Dead Hour broadcasts and the occasional dead.net MP3 post, the still-shifting picture of 1975 shows the band improvising song forms over leisurely months up in the hills outside Mill Valley, at the seat of the new hippie empire. In the neighborhood was David Crosby, who stopped by to jam not infrequently, working out on endless takes of “Homeward Through the Haze” and “Low Down Payment.”

And there was Ned Lagin, too, the band’s biomusic composer friend, present on nearly all of the band’s song-shaping sessions through June (including some jams on Lagin’s own material), contributing dense, conversational keyboards side-by-side with Keith Godchaux’s earthier filigrees.

The musicians at work were the cream of the new California culture, creators of their own music, proprietors of their own record labels, Grateful Dead Records, for the Dead proper, and Round Records, for their side projects. Lately, too, there was Round Reels, Jerry Garcia’s fledgling film house, at work producing what would become The Grateful Dead Movie. The music from Ace’s reflects the band’s vast ambitions: the conceptual jamming material that would become Blues For Allah, the discarded themes like “The Nines” (a long- lost rhythmic companion to “The Eleven,” “The Main Ten” and “The Seven”) and “The i8” and “Garcia’s Folly”—and the very process of collective composition itself. Ned Lagin was leaving, Mickey Hart was returning. In a changing world, the Dead’s all-encompassing countercultural enterprise was coming into one last beautiful collaborative bloom before lurching into an unwilling transformation of its own.

In the spring, the last Americans were airlifted out of Saigon and the Vietnam War and the ‘60s were really, positively, unquestionably over. It was at a session at nearly the same historical moment that (as Browne reveals in So Many Roads) in-house record company mogul Ron Rakow arrived with the news that the band was running low on finances. Garcia’s film project was eating up funds. So were the BMWs parked outside. Something dark was lurking in the hills of Marin County, coming to cash old karmic debts. It wouldn’t transubstantiate into physical form until later in the year, after the band’s sparkling One From the Vault show at the Great American Music Hall.

It is this new dark piece of 1975 that rings clear in drummer Bill Kreutzmann’s new memoir, Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams, and Drugs with the Grateful Dead, written with Relix contributor Benjy Eisen. In it, Kreutzmann writes (spoilers coming) about both his extreme misgivings regarding Mickey Hart’s rejoining and the opiate addiction Kreutzmann fell into when the hiatus really began in 1975, historical facts that the band’s original drummer says are inseparable. It is a measure of the musicians’ isolation during their time off that Kreutzmann’s sole partner in the band’s rhythm section through most of the band’s history through that point, Phil Lesh, also fell into a pattern of deep substance abuse almost immediately after the break began, as he recounted in 2005’s Searching for the Sound. It was then, too, as several biographies note, that Garcia would begin his own slide into heroin addiction. By many measures, late 1975 was when the drugs turned bad for the core of the Grateful Dead.

But that wasn’t the case at the Great American Music Hall on August 13. “It was a very bright, clear, expressive night for the whole band,” Kreutzmann writes. The recording rings true to this memory, though the band’s official release of the show changes a few slight but revealing details. Reproducing the private event’s original fancy-fonted invitation, the One from the Vault cover alters the names of Ron Rakow, Round Records and Al Teller, United Artists (listed as the event’s hosts) and replaces them with Grateful Dead. In fact, the tiny Great American show served to announce the band’s new partnership with United Artists, who had saved their ass, financially speaking. The August 13 show, then, signaled the end of the band’s do-it-yourself Grateful Dead Records and, in a way, the band’s broadest countercultural ambitions, subsuming them back into the ooze of the mainstream record industry.

Similarly, and wisely, the album’s producers edited down Graham’s band introduction, too, omitting a very inside-baseball aside pertaining to Rakow. It’s a better listen, but it makes the magical lead-in seem slightly smoother than it was. On the official recording, it’s hard to tell which musician has the idea to start building up behind the famed rock promoter (who wasn’t actually promoting this particular show), like a collective decision by a linked-together group mind. On the unedited version, it’s a lot more clear: Garcia (big surprise) signals it while Graham spiels about a lost bet. Both versions end the same important way, though, with Graham unequivocally introducing the band on stage—“Will you welcome, please, the Grateful Dead.” When the show was broadcast nationally soon thereafter, it was the first time they had publicly admitted to that name in some 10 months. The cat was out of the bag, alive but Dead.

“I think it’s a, perhaps the, crucial year in understanding the Dead’s career in summing up their musical and professional experimentalism and pointing the way forward to the quite different band they became post-retirement,” says Melvin Backstrom, a Ph.D. candidate at McGill University whose thesis-in-progress is titled “The Grateful Dead and Their World: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1965-1975.” For the Grateful Dead, 1975 was—and always will be—simultaneously an ending, a beginning and something completely undetermined.

In a year where four of the band members had their names on Round Records albums, there was an enormous amount of possibility swirling around Ace’s. Besides Lagin and Crosby with his “brain surgeon weed,” one day, Steve Brown remembers even Van Morrison showed up. “Van was living in Fairfax and was invited by Weir, I believe, to check out his new studio. He seemed comfortable but quiet during the band’s rehearsals.”

There was Hart’s rich Rolling Thunder album in progress. And there was Keith Godchaux, writing songs with his brother Brian for the Keith & Donna album. One, “Showboat,” the Dead even rehearsed the day before the Great American Music Hall. Playing it through once, and probably only once, Keith sings in a voice far sweeter than any renditions of “Let Me Sing Your Blues Away.” They stumble a little, but it sounds almost ready. “That’s neat,” Garcia says as the last chords are still hanging, a future passed before its present. “Got any other ones?”