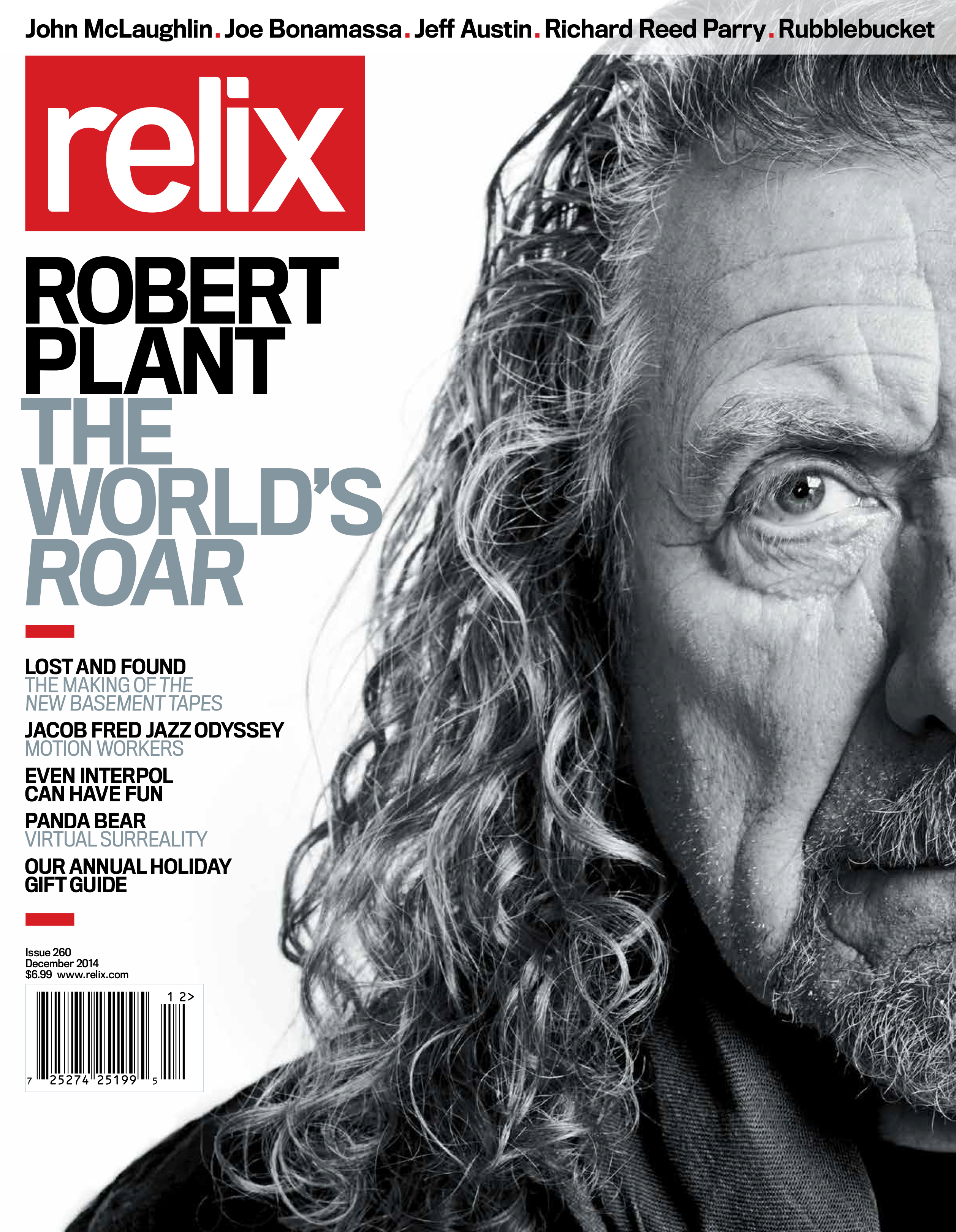

Robert Plant: The World’s _Roar_ (Cover Story Excerpt)

As 2014 comes to a close, we’re honored to have the legendary Led Zeppelin frontman Robert Plant grace the cover of our December issue. Below, enjoy an excerpt from the article where Plant speaks to Alan Light about his new band, The Sensational Space Shifters and their latest album, Lullaby and… the Ceaseless Roar.

For a limited time, Relix will be offering a complimentary issue delivered to mailboxes across the United States. To obtain your free trial, which includes the December issue, click here.

At first glance, you don’t notice him.

It’s a little hard to believe—he is, after all, one of the most recognizable, distinctive and flamboyant frontmen in rock-and-roll history. But right now, with his band of seven musicians arranged more or less in a circle on the stage of the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, N.Y., the guy in jeans and a faded gray T-shirt, with his hair tied up in a bun and his back to the empty room, just seems like one of the group.

But then, they count off the song and that voice comes out, and he doesn’t need to turn around for you to know that it’s Robert Plant. Still, he’s not delivering the keening, spine-tingling wail that filled stadiums with Led Zeppelin; it’s a more nuanced sound he’s working with as he rehearses with his band, the Sensational Space Shifters, on this September afternoon prior to the first stop on a quick, eight-show U.S. tour. And as they start to play, it’s the song that takes a minute to register—it’s “Nobody’s Fault but Mine,” the searing Blind Willie Johnson blues lament that Led Zeppelin turned into a jagged assault on the 1976 album Presence, arranged instead with a loping, back-porch rhythm and multi-part vocal harmony.

This air of uncertainty all makes some kind of sense. Plant has spent his recent years sneaking up on expectations, surprising people with his musical choices and earning a newfound, hard-earned respect that no one would have anticipated. For decades after Led Zeppelin broke up in 1980—following the death of drummer John Bonham— his solo career was of sporadic interest; the music was never subpar, but his direction often felt aimless or uncertain. When Plant joined forces with his old foil Jimmy Page in the ‘90s, merging his own interest in Arabic styles with the Zeppelin catalog and similar blues-based approaches on the MTV Unplugged project No Quarter and the Walking Into Clarksdale album, the results were both successful and inevitable letdowns. Following those projects, several Plant albums in a row failed to break the Top 20.

Then came the pivotal year of 2007, when he joined Page, John Paul Jones and Bonham’s son, Jason, for the triumphant, one-night- only Led Zeppelin reunion show at London’s O2 Arena —more than 20 million people around the world entered the ticket lottery—and also released Raising Sand, his collaboration with bluegrass colossus Alison Krauss that won five Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year. It was followed by another glorious exploration of American music, 2010’s Band of Joy, and a magnificent tour. Four years and a lot of global travel later comes his 10th solo album, lullaby and…The Ceaseless Roar, a swirling, thrilling blend of African, Middle Eastern, rock, blues and folk music that may be the most daring work he’s done since the Zeppelin days.

Seated in his spacious and homey, though not extravagant, dressing room—overlooking the local train station—a single flowing, print shirt hangs on a rod, waiting for show time. The 66-year-old Plant insists that he’s been on the same mission all along. “I think so, starting from when I was about 15,” he says. “It’s the flexing of public perception and people buying into the idea that’s fluctuated. In the beginning, there was nobody there—just an empty room, maybe three people. And in 1965, it was free to get in! And then through time, the amazing pinnacles of exchange with energy, which included absurdities and cherry bombs and social disease and penicillin immunity, and stress and some joy, and freedom and capture and prisons—all those things spin around, and we end up here, in this fancy dressing room. Not bad, all things considered.”

Plant is the rare celebrity who is actually bigger than you imagine—long legs, broad shoulders, huge head. He laughs often as he stretches out across a low sofa, sipping water and recounting his journeys and adventures. (He displayed his sense of humor on some recent television appearances, singing doo-wop into an iPad with Jimmy Fallon and jokingly handing Stephen Colbert a joint on air.) Mostly, though, he lights up when he talks about music, drawing connections, dropping very difficult-to-spell names, describing sounds and voices and rhythms from far-flung corners of the earth. His enthusiasm and sense of discovery only seem to have expanded with time.

“He’s a walking encyclopedia of everything that’s good musically,” says Buddy Miller, who played guitar on the Raising Sand support tour and co-produced the Band of Joy album. “He’s one of those sponge guys; he just absorbs good stuff from everyplace and, through his own filter, something new comes from it. Robert never wants to revisit the past just to regurgitate or repeat it. Any time we looked at a Led Zeppelin song, it would never be from the place of listening to it or remembering the riffs—it was, ‘Let’s distill it down to what it was at the germ and run it through who we are now.’”

“I admire his longevity, creativity and his storytelling, but it’s his youthful enthusiasm that I’m most impressed with,” says Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys. “Growing up a lover of blues music was a lonely thing for me—absolutely none of my friends shared my passion for it, but I couldn’t get enough. Robert and I both grew up obsessed with the same images of rural American mystery, those potent regional sounds from all around the U.S., not just the Delta. When I hang with Robert, it’s like I finally get to share that excite- ment with someone.”

Though Plant has spent most of his lifetime wandering in pursuit of musical encounters, he claims that his time spent in the American South seemed on its way to becoming a permanent arrangement.

“I had the most amazing late honeymoon through my adventures in Nashville, [Tenn.,] with the great game that is that kind of music,” he says. “The quality and the resonance of the American musicians I was with were unparalleled. I thought that I was going to be spending the rest of my days here in America. But the thing about being British is that you tend to start listening to songs from the Appalachians and the Smoky Mountains, and quite a few of them come from where I’d run away from. So I just kept on getting drawn back to the U.K. more and more.

“Also, as it happened, at that very time, my soccer team started doing very well in England,” he continues. “And I was getting all these summons from my two boys going, ‘What in God’s name are you doing out there? The place is on fire back here, and the team is top of the league and people are crying in the streets, grown men are pulling their own heads off, the birth rate has gone up in the city of Wolverhampton, people are smiling again.’ So it was a calling to go back—for every reason really.”

Plant maintains that he could tell that the Band of Joy—which started after he opted out of a second album with Krauss—had run its course. Miller needed to work on the music for the ABC series Nashville, Patty Griffin had her own record to make, 2013’s American Kid. (Presumably, the end of his relationship with Griffin, with whom he was living in Austin, Texas, was also a factor.)

“With a band, you’ve got to know that it goes somewhere that matches my energy and my idea of where it might go,” he says. “And, I think, with the Band of Joy, everybody sort of naturally fell off, back into things that they know they can do, because it wasn’t a writing band. I learned how to sing better, but I also learned that a project can get to the end of its lifespan and kind of fizzle out.”

“Before he started this new record, he came over to my house and we wrote and recorded a bunch of songs,” says Miller. “But then, it was time for him to go home. He just goes where his heart takes him.”

Returning to England, specifically to the Black Country region where he grew up, proved to be a more powerful experience for Plant than he anticipated. “Going back to the particular place I come from, it’s a very visual, panoramic feast that I’ve ignored,” Plant says. “There’s a lot of emotion packed into it as well. And that was a very arresting feeling for a guy my age—I missed it, but I didn’t know I missed it. I hadn’t seen it even when I was there. I took it for granted, and I wanted a new start, I wanted to get the fuck out of there.”

While Plant was home, some of the musicians who had played with him on several albums under the name the Strange Sensation were performing as part of the Hay-on-Wye Book Festival. “There were all these great authors, writers, statesmen, politicians—and in the middle of it, these four guys were playing, and they were kicking up one hell of a storm,” he says. “They were playing in a huge tent, on the side of the Misty Mountains, and I heard the unadulterated power, unabridged and not at all self- conscious, of just letting go. I thought, ‘That’s a long way from what I’ve been doing, I wonder if I can still do that stuff?’ So from Townes Van Zandt and George Jones, Charlie Rich, Lefty Frizzell and all that stuff, I was zooming right back into West African trance.”