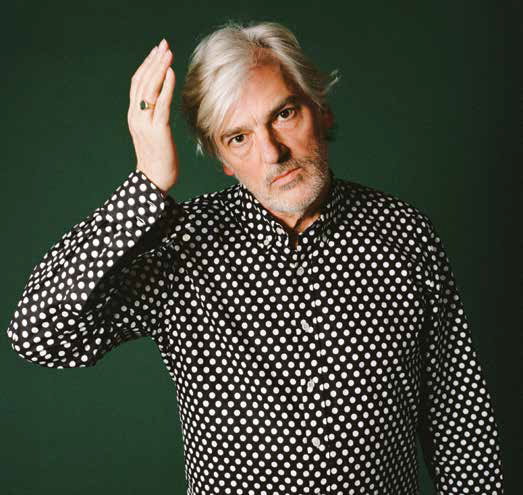

My Page: Robyn Hitchcock “Psychedelic Blues Again”

Psychedelic blues is an odd coupling, like shrimp in pistachio ice cream. If there’s an emotion associated with psychedelia, then it is detachment, wonder or, perhaps, elation. Blues is all about feeling. A line about the way life hits you, or you hit life, is sung twice—then, the payoff comes with the third line. The blues might be a bleak joke or a hymn of desire. It’s as close to the human heart as psychedelia is remote.

Yet psychedelia was born into human ears on the waves of the blues. At the end of the street where I’ve been staying this summer, on the Isle of Wight, a mournful statue of Jimi Hendrix huddles, as if trying to shrug off the English rain. I saw Hendrix and Jim Morrison play their almost final shows here in 1970. Jimi and Jim were both masters of the 12-bar blues, both involved in the elastication of the old Afro-American form into something crazed and shamanic. I watched Hendrix pace the cage of “Red House” like a trapped puma, before tearing it into glorious shreds. Jim Morrison took the phallic assaults of “Crawling King Snake” and “Back Door Man” into much darker places.

Country Joe & The Fish captured the morose glow of an LSD comedown perfectly in “Bass Strings” and “Crystal Blues.” One of my fondest musical memories of this century is sitting in with Barry Melton, their exuberant lead guitarist, in La Rochelle in 2006. Meanwhile, back in 1968, Jorma Kaukonen piloted Jefferson Airplane through a tantalizing “Rock Me Baby,” echoed by the Grateful Dead’s spooked take on the old Rev. Gary Davis blues “Death Don’t Have No Mercy”—both released on live albums that finally realized the potential of those trippy ensembles.

The patron saint of rock (when it shed the “& roll” and got serious) was Bob Dylan. He had sliced clean through psychedelia and out the other side before the term was even coined. He embedded mindcurdling dystopias—at once hilarious, romantic and menacing—in the 12-bar frame. “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” and “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” were transformed live, courtesy of The Hawks (The Band in overdrive embryo), into a show that Phil Ochs once described as “pure LSD.”

Ten years on, in the New Wave Winter of 1977-78, I was a second-generation Beatle trying to negotiate the angry puritanism of punk rock, as were other Beatle kids like Elvis Costello, Andy Partridge and Difford & Tilbrook. They somehow made it past New Wave Immigration, but The Soft Boys got stopped at the border for having long hair and guitar solos. Guilty as charged! No band where Kimberley Rew’s creamy, abrasive Stratocaster battled it out with my spindly, spiky Tele was going to go over big in those Stalinist times. And we had three-part harmonies (or tried to)—deduct 10 points for that!

But we were not flower-powerists: The momentum of the mid-1960s had drained away into hairy inertia. The punks were right in wanting to shave music into something more to the point. We just disagreed with them as to what the point was. Eventually, Oasis came along and married The Beatles to the Sex Pistols, reconciling everything.

Back to the psychedelic blues: The two personal heroes that I brought to The Soft Boys were Captain Beefheart and Syd Barrett. Syd was originally called Roger, and Beefheart was born Don Van Vliet, incidentally. Both men were trained as visual artists and after tortured careers in the music busines —Barrett lasted barely three years in its toxic tank—spent the rest of their lives painting.

One of the key elements in psychedelia is synesthesia: You can sometimes see the music that you’re hearing. As artists, Barrett and Beefheart were masters of this. You don’t need to adjust your mind with drugs, headphones and dim lights to see the music that they produced. Both of them started from Bo Diddley and Howlin’ Wolf: They favored rampant grooves with resounding open E-strings pulsing in triumphant mania, over which they detonated their cargo of words in the mind’s ear. Beefheart was more blues, Barrett had some pop in his chart—guess which one was a Beatles fan?

With the aid of his cult captives, The Magic Band (long-term inmate John French, especially), Captain Beefheart took his existential testosterone from straight 12-bars like “Sure ‘Nuff ‘n’ Yes I Do” into the fractured jazz erotica of “Neon Meate Dream of a Octafish” and back out into the swamp funk of “I’m Gonna Booglarize You Baby.” The most exhilarating rock show I have ever seen was Beefheart and The Magic Band in 1973 in Bristol. It was also the loudest. Beefheart stalked around the stage like a bellowing farmer, scattering his musicians like lysergic chickens. The music was a fearless, intricate clatter and yet—it rocked! This was no academic piece of avant-garde.

I never saw Syd Barrett, though I may well have passed him in the street of Cambridge during my Soft Boys days—I wouldn’t have recognized him. He had reverted to being Roger—pudgy with a shaved head and thrift-store clothes. He is, sadly, as famous for his breakdown and self-erasure as for his _____ music. (The blank is there because I can’t think of an adjective to describe it.) You may well know the Pink Floyd singles that he wrote: “Arnold Layne” (produced by Joe Boyd, who helmed my new LP) and “See Emily Play,” or the first, maniacally dazzling Floyd album. Barrett’s solo records are a bit tentative—he was apparently dissolving himself in acid then—but to me (and so many other musicians, from Graham Coxon to David Bowie) they are utterly—again I’m lost for words—but they contain an impossible beauty. These songs couldn’t really exist, and yet somehow (particularly courtesy of producer David Gilmour) they do.

I have never felt the presence of someone so directly transmitted, as if they were whispering into my ear, as I have from listening to Syd Barrett. His disintegrating personality reveals his lonely, vital soul. To me, he was singing the blues as surely as Robert Johnson. Hmmm. Maybe it’s time to plug in and turn on again…

***

Psychedelic troubadour Robyn Hitchcock released The Man Upstairs, his 20th solo recording, in August.