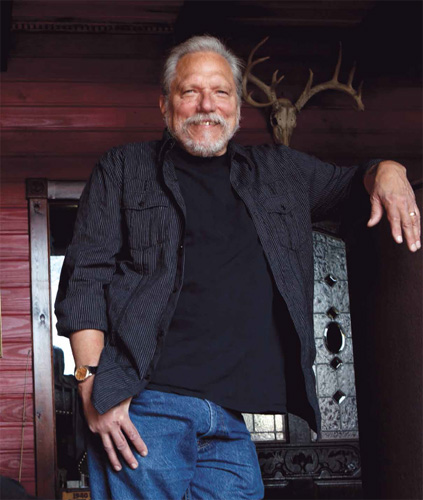

Jorma Kaukonen Takes Off Again

When Hot Tuna last played New York’s storied Beacon Theatre in December, fans were on their feet and ecstatic when guitarist/vocalist Jorma Kaukonen, bassist Jack Casady and the rest of the band were joined onstage for several tunes by former Jefferson Airplane vocalist Marty Balin. It had been decades since Balin and his two former Planemates had shared a stage in any significant manner, as most in the audience were well aware. Yet here they were, happily tearing through “Somebody to Love,” “White Rabbit,” “3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds,” “Plastic Fantastic Lover” and a killer “Volunteers” encore—all Airplane classics— as if they’d been doing so all along.

Just a few weeks later, when Tuna hit San Francisco for a Fillmore date, the rumor mill kicked into overdrive as a viral selfie depicted Kaukonen, Casady and Paul Kantner—who co-founded the Airplane with Balin and Kaukonen in the summer of 1965—radiating big smiles. For many years, the relationship between the Tuna mainstays and the Jefferson Starship frontman was characterized as vitriolic. Now, fans rightly couldn’t help but get their hopes up: With the Airplane’s 50th anniversary right around the corner, had the rifts finally been healed? Might a full-scale tour, or at least a reunion gig or two, possibly be in the cards?

The answer, Kaukonen states quite authoritatively, is not a chance. “I called Paul up when we were in town and took him out to dinner,” he says. “I figured, ‘Look, we’re not gonna work in a band together again, regardless of what other people might want; it’s just not gonna happen. But I see no reason to be adversarial.’ [The Airplane] is something that cannot be replicated. That stuff was exciting to me back then because it was all still new. We were discovering this and learning that, and that’s not the way it is anymore. We tried to recreate it with the ‘89 tour,” he says, referring to the Airplane’s last major regrouping, after which singer Grace Slick retired permanently from music. “I don’t think the band sucked, but we weren’t kids anymore so we just didn’t have that thing. Besides, the bottom line to this discussion, beside all of the meandering philosophizing, is that Grace doesn’t sing anymore. And without her, it’s impossible. So she’s really taken the pressure off me.”

With that hovering question tidily disposed of, Kaukonen is more than happy to talk about what he will be doing for the rest of this year and, he says, “as long as I can.” For now, that means getting the word out about his new solo album, Ain’t in No Hurry (Red House Records). Recorded at his own Fur Peace Ranch Guitar Camp in Meigs County, Ohio, the 11-track set was produced by multi- instrumentalist Larry Campbell, a crucial component of the Tuna lineup for some time now, and features the band’s current muscle: longtime Hot Tuna mandolinist Barry Mitterhoff, drummer Justin Guip and vocalist Teresa Williams, who is also Campbell’s wife. Myron Hart, a friend of Kaukonen’s who contributed to his previous solo recording, 2009’s River Of Time, handles bass duties, save for one track, a wholly reimagined take on “Bar Room Crystal Ball,” originally rendered in a considerably more electric fashion on Hot Tuna’s 1975 Yellow Fever album. That’s where the other Tuna guy comes in.

“I’d thought about re-doing ‘Bar Room Crystal Ball’ for a while because Larry, Teresa and I had played it, with Jack and by ourselves, over the last year or so,” Kaukonen says. “I always liked the song. It started out as an acoustic song and I always wanted to do it like that—I like the lyrics and I wanted them to be able to be heard. So we cut the song and we had everything but the bass part. Myron played bass on most of the other songs, but Larry and I said, ‘There’s only one guy who can play this.’ So I called Jack up and I said, ‘Jack, listen. I always wanted to redo ‘Bar Room Crystal Ball’ as an acoustic song. I just did it and I want you to play bass.’ So Jack says, ‘Well, Jorma, don’t you think that me playing on a Hot Tuna song on a Jorma project crosses boundaries and blurs the lines?’ He went on and on and when he stopped to take a breath, I said, ‘I’m gonna say one thing, and that one thing is, ‘I played on your album.’ That did it.”

Three other original Kaukonen compo- sitions surface on the album for the first time. “In My Dreams,” he says, was built around the phrase, “We never seem to age in my dreams,” which came to him one morning while on tour. “I realized that it was a great idea for a song, and I jumped out of bed and did not turn the TV on, did not touch my phone, did not turn the computer on,” Jorma says. “I sat down and pretty much wrote the song. Then I had a couple of reflective days, and on one of them, I wrote ‘The Other Side of the Mountain.’ And then, ‘Seasons in the Field’ is the other one. Larry said, ‘You need to do this yourself,’ so I did it because I trust his musical judgment. I had been thinking about the flow of things in my life, and while it’s not a completely autobiographical song, this was how it came out. I had a little help from Larry on the bridge, which is why he’s listed as a co-writer, but lyrically, it just came to me.”

The other seven tracks range from a Carter Family number, “Sweet Fern,” to a few old blues tunes—among them the title track, “Brother Can You Spare a Dime,” Thomas A. Dorsey’s “The Terrible Oper- ation” and “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” which Kaukonen used to play in his pre-Airplane days with his old friend Janis Joplin. One tune, “Suffer Little Children to Come Unto Me,” bears a curious authorial credit: Words and music by Woody Guthrie; New music by Jorma Kaukonen and Larry Campbell.

“I’m one of Nora Guthrie’s pals,” Kaukonen says—Nora being Woody’s daughter—“and Woody has thousands of poems nobody has ever seen or heard. This was one of them. Over the years, she’s always said, ‘If you want some lyrics, you can put some music to one of them.’ When I started to do this record, I emailed her and I said, ‘Hey, listen, I’m finally doing another record. Is that offer still open? Do you have a couple of Woody poems you think would make good blues songs?’ She sent me four sets of lyrics via Dropbox, photo- graphs of Woody’s manuscripts in his own hand. It was so cool. Three of them were like beat poems—I can hear some sort of a jazz thing in the background. Then there was this one, ‘Suffer Little Children.’ It was actually five verses, four lines in each verse. Just looking at it, I said, ‘That’s the one we’re gonna do.’ Larry and I were sitting around at the Fur Peace Ranch, I picked up the guitar and started messing around and we wrote that song in about 20 minutes. So Larry and I have now co-written a song with Woody. I hope he likes it.”

Listenng to Ain’t In No Hurry, it occurs to the listener pretty quickly that not only has Kaukonen’s singing voice not degraded with age, but it’s actually improved markedly. His guitar work, too, is more nuanced and intimate than when he was a younger man. At 74, he’s matured into one of the elder statesmen whom he studied so religiously and emulated so lovingly while coming up during the ‘60s and ‘70s. Whether wailing on electric guitar, as at the Beacon show, or spilling out faultlessly framed acoustic melodies, Kaukonen has learned much about economy and communication over the years. His music today fits like a pair of broken-in but still sturdy boots: comfortable, reliable and warm but still tough and solid. Kaukonen has given much thought to his own journey and where he now finds himself.

“Somebody recently asked me about retiring,” he says, “and all I could think of was: ‘Why, so I can play the guitar more?’ The traveling is not as much fun, but I get to see a lot of good stuff, and at the end of the day, when we go to work, I get to play music and, most of the time, people listen. I never feel like it’s just a gig. I really like it. I fell in love with the guitar years ago and never fell out of love with it. It’s still always fun to play in front of people.”

He takes a breath and continues, “And the good news for me, as an artist, is that my fans allow me to change things. They don’t expect the guitar solo from ‘Hotel California’ the way an Eagles fan would expect that. I don’t have to do that, and it’s a good thing that I don’t have to do that because I’m not sure that I could. It’s not in my nature. Take a song that I’ve played for half a century, like ‘Hesitation Blues.’ It will always be recognizable as that song, but there are always little quirks and things that happen. And the thing with me, as a guitar player, is that I’m constantly learning stuff. Sometimes you try stuff out, sometimes it doesn’t work. The good thing about being a guitar player and playing live is that if you do something you don’t like, nobody dies; you just try to change it the next time.”

Even when he is not on the road or in the recording studio, Kaukonen is constantly learning new things—and much of that happens while he’s teaching others. Fur Peace Ranch has been going strong for 18 years, and each season brings both new and loyal returning students eager to pick up tips from Jorma, as well as his ever- rotating cast of guest instructors, to Ohio.

“Obviously, whenever you start doing something,” he says, “you hope that it’ll have long legs and last a long time, but there’s no way to actually conceive of what’s going to happen because, even as you make plans, you can’t plan the outcome. Whatever grandiose plans we had for the Fur Peace Ranch, the reality has superseded them. It’s so rewarding. People seem to get so much out of what we have going on that it’s difficult to quantify it without sounding sappy, but you just feel good about it.”

Talking to Jorma Kaukonen, being around him, you can’t help but bask in that feel-good glow a bit, cheering him on as he talks about the mutual admiration society that he and Casady, himself now 70, have maintained since they first started playing music together in the late 1950s. “Jack and I are two very different people and we really cut each other a lot of slack,” he says. “At the end of the day, we’ve always treated each other with at least a modicum of respect. If we don’t agree about something, it doesn’t matter. And when we play music, we listen to each other and we play together.” And you’ve got to admire his devotion to friends and family, to grin along with him as he proudly notes that his high-school-age son and 9-year-old daughter have inherited the music bug that he’s had all his life. (“I probably wouldn’t have known about Bruno Mars if it hadn’t been for her,” he says. “He’s really talented and exciting.”)

Mostly, though, you’ve simply got to admire an artist who’s managed to come so far and accomplish so much without his own ego getting the better of him, without turning to bitterness or becoming snide or leaving a trail of enemies in his wake. Ask him to evaluate his own life’s work and he humbly admits, “Some songs are better than others.” When asked which of them are most likely to survive long after he’s gone, he prefaces his reply “without patting myself on the back too much” before naming “Embryonic Journey,” the lustrous guitar instrumental that adorns the Airplane’s 1967 breakthrough album. “I’d say it’s got as good a chance as anything.”

But neither the future nor the past wins out over his interest in the right now. In the liner notes for Ain’t in No Hurry, Kaukonen writes, “At this point in my life, perhaps I should be in more of a hurry, but for me, it is more important that each piece fits in the right place at the right time.” Expanding on that, he says, when you get to be his age, “Life is different. And I’m fine with it. You might as well be because that’s just how it is.”