JJ Grey: Mofro’s _Glory_ Days

Photo: Stuart Levine

That other life is looming. The one that excites in the optimism of a new album release, and unfolds with tour buses and travel schedules. It is rising like the sun, visible, tangible—taking inevitable shape. Not long from now, JJ Grey won’t be home fixing a pump on his well, driving his daughter to school or greeting a buddy who’s dropping by with homemade wine as he is on this Wednesday morning in January.

In a few weeks, the 47-year- old singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist will be far from his Jacksonville, Fla., digs, on the road with his band Mofro in support of their new album, Ol’ Glory—knocking ice off his boots in frozen metropolises like Albany, N.Y., Boston, Pittsburgh and Chicago before going transatlantic to meet the spring in Europe. These are the early days of 2015, but for Grey, they are a last chance to unwind— perhaps surf a few more neatly curling sets before the approaching two months of concert dates reach their international conclusion at Australia’s Byron Bay Bluesfest in early April.

It wasn’t always easy for Grey to throttle back. His output during a career that ostensibly began in 2001 with his Blackwater debut has been a model of prolificacy, including a streak of six albums in six years for the famed Alligator Records that kept him perpetually onstage and seemingly in constant motion. Even Ol’ Glory emerged from the tightest window of available time in the summer of 2014 between East and West Coast appearances with his Southern Soul Assembly—a quartet comprised of Grey, Marc Broussard, Luther Dickinson and Anders Osborne—and his own packed calendar of Mofro shows.

Somewhere among the dividends an album’s release provides, amid creative expression and commercial reward, is the opportunity to grow and develop as an artist. Grey had proven that he could lead a band—certainly he’d shown that he could write and perform his blistering brand of rattlesnake rhythm and soul for legions of audiences increasing in size around the world—but that constant motion, that pursuit, had him on the verge of spinning out his tires.

“There was a point, around 2009 or 2010, when I had an epiphany. I realized that I was asleep at the wheel in my life. If I was on the road, all I could do was fantasize about getting home to see the family, eat at Chowder Ted’s and go surfing. If I was home doing those things, I’d be fantasizing about going back out on the road and playing music,” admits Grey. “It’s kind of a tiresome, lonesome, stressful way of living. I’d think I saw a sunset or a clear, cool moment surfing out in the ocean. I’d think I had experienced it, but I really didn’t. Wherever I was, I was never there. It was always where I was going to go next.”

According to Grey, things began to change following this moment of profundity, the resulting professional trajectory tilting steadily upward. With one album after another getting nearer to a defined musical target, his latest, Ol’ Glory could very well be his bullseye, an effort that Grey agrees couldn’t have happened until now. “However many years I’ve been doing this, I’ve been trying to make an album that sounds like that. It’s kind of like the tension for us to stay alive, like a heartbeat—it tenses, then it relaxes. You can’t find it, it just has to happen, but it has to happen because you prepare yourself for it. I feel like with this record, I’m one step closer.”

The coastal town of St. Augustine, one of American’s oldest settlements and home to Retrophonics Studio, lies a little less than an hour south of Jacksonville. Since 1978, it’s been a musicians’ clubhouse, nondescript, still under construction and stocked with the vintage gear that players like Grey and his band salivate over. In its early years, it was a haven for punk rockers that were turned away elsewhere, and it’s here that Grey has recorded seven of his nine albums, including his latest. His rented condo was cruising proximity to both the beach and the studio, and Grey spent the sessions catching some waves in the mornings and making music with his Mofro mates in the afternoons.

True to his shifted mindset, Grey’s comfortable confines were imperative, as he wasn’t looking to break ground as much as he was trying to stand more firmly on a foundation he had been building for over a decade. “I try to avoid the idea of flag-planting, like, ‘This is new.’ Of course what I’m doing isn’t new,” Grey says. “All the stuff that matters isn’t new. New and fresh? If you seek that, you’ll only fool people, or fool yourself, and that’s not the kind of light I’m about.” Returning to helm the production was longtime collaborator Dan Prothero, who had dialed the knobs for a half-dozen prior entries in the Grey discography and whose own Fog City Records imprint distributed Mofro’s first two albums. Yet something was different this time around, exemplified best in the construction of Ol’ Glory’s title track.

It began with a drumbeat that Grey played, liked and recorded at his home studio. Then a bass line and a guitar riff that, too, came quickly and met his favor. He looped the backing instruments onto tape and let inspiration do the rest. “Within minutes of doing those things, I grabbed the microphone and I just hit record,” Grey recalls. “I didn’t have anything written. Everything you hear on the record— what I sang then—I just made up the words as I went.” What emerged was a gripping, soul-baring, ad-libbed, kneel-down-and-testify, force field of funk sure to be a concert favorite, and nearly eight minutes of tape that were in danger of never being heard by anyone other than the creator and his band.

Prothero and Mofro drummer Anthony “AC” Cole convinced Grey to keep the one-take vocal wonder after listening at Retrophonics—a concession that Grey, a self-confessed micro- manager, likely wouldn’t have made in the past. “Oh, yeah, definitely I would have re-sung it,” he admits. “You’re in the studio. You need to re-sing it.” With his looped groove serving as a guide, the band recorded its parts fresh, but, thankfully, Grey preserved that original, rubbed raw vocal. Encouraged by improved technology and a level of relaxation that he’s discovered when singing alone, Grey, in fact, tracked the entirety of the vocals on Ol’ Glory at the home studio. “It was good to get out here by myself and get these songs to feel lived in, vocally. I felt like I took more chances.”

Taking chances, as well, meant extending his trust to the band—a trust he had been reluctant to offer so freely on earlier efforts. Demo tapes that had previously served as blueprints were now presented more like outlines or sketches of the songs. Suggestions about tempo or groove came during soundcheck rehearsals of the new material with Grey stimulating the flow of ideas rather than dictating them. “I barely had to say anything about anything,” Grey says. “I wanted to hear their thing. The fact is that I can trust them. I can trust that they are going to be way nastier than if they try and learn note-for-note some crap that I did.”

Grey still has deep reverence for Mofro, and though the member- ship has changed over its 14-year lifespan, the influences that have informed its direction remain constant. Donny Hathaway, Otis Redding and Jerry Reed hang over him like the dozens of pecan trees that he farms at his Florida homestead, yet his Southern roots didn’t always extend so strongly into his music. Indulgences from his skater youth, like Dead Kennedys punk icon Jello Biafra, English New Wave pioneer Elvis Costello or heavy metal stalwarts Black Sabbath, ran in counterpoint to regional heroes—an eclectic blend that Grey says still exists, but is less apparent both in attitude and in repertoire.

“For a long time, when I was real young and just starting out, I tried my best to sound like anything but where I was from,” concedes Grey, clearly remembering times as a teen when “whiskeys” was a common derisive label for fans of Southern music. “When I quit trying to sound like somebody from somewhere else, this happened all by itself. Doing what I’m doing now takes no effort.”

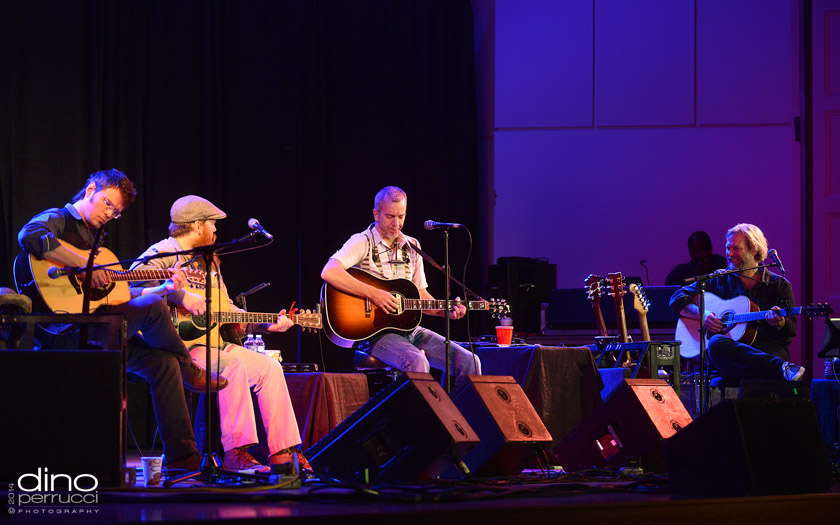

More of a bond than a band, the Southern Soul Assembly’s Tour four members—each of whom hails from a different Southeastern U.S. locale—embodied the effortless embrace of their respective musical and geographic origins during two short spring and fall 2014 runs. Their live highlights often included richly detailed and personal stories that preceded each song’s performance, introductions that were—particularly in Grey’s gregarious and animated expositions— frequently as entertaining as the music itself. Bookending the Ol’ Glory recording sessions, the tours also exposed Grey to a work ethic employed by his SSA peers that he had not always aspired to on previous albums.

“Listening to them at their craft, all of them, it’s like, ‘Man, I need to bring it on this record,’” Grey reflects. “After talking with them about their process, I decided that I wanted to take a more active role—get down there three or four days early instead of just walking in the first day, setting up, jamming and getting out of there. They put a lot of effort and time into that part of their craft, and I haven’t, and I needed to. That inspired me.”

Dickinson, a much in-demand guitarist for the North Mississippi Allstars and The Word, whom Grey enthuses, “sings on an instrument with a Southern accent,” guested on Ol’ Glory for two tracks. The two found their breaks around the same time—and in similar fashion— recurrently toured together as they came up through the circuit—but it was an invitation from Grey to be part of the SSA that allowed Dickinson more time to reconnect with his friend.

“I’ve known JJ a long time,” Dickinson says. “Doing the SSA tour and getting to know JJ again, I realized that he has been such an amazing example of somebody turning his life around.”

Dickinson recalls a younger Grey drawing on his anger as his muse, but sees a man finding the contrary in his middle age years. “He’s even more intense now, but he’s focused and radiating posi- tivity,” Dickinson observes. “You know where he stands when he’s singing to his people. I’ve never seen anybody make such an intense change.”

The seeds of change were already there, if somewhat buried, embedded in songs going as far backas his first albums. Grey suggests a quote from Col. Bruce Hampton, the de facto godfather of the Southern jamband scene: “To seek is to deny.” Likening it to a scientist’s search for a formula, Grey says the answer was in the notebook pages of his music, like entries in a diary, but he was unable to see it. “One day, I looked at the lyrics I had been writing, all the way from when I first started. It was scary,” Grey says. “No matter what the subject matter, every song was telling me to wake up.”

As he’s matured, those initial pistons of motivation have evaporated, the clichéd incentives of girls and money that star in the dreams of many prospective rock and rollers. He knows now why he does what he does. “People that come to the shows—I look out and see them smiling and it makes me smile. It’s an infectious thing. I do this to help myself, and in helping myself, maybe that can help somebody else.” If to seek is to deny, then maybe to find is to enjoy. That other life is looming, and JJ Grey is ready to enjoy it.