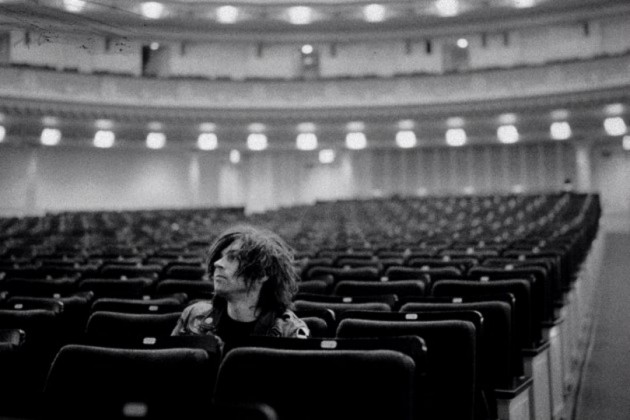

Interview: Ryan Adams Reflects on ‘Heartbreaker’

Ryan Adams’ Heartbreaker is often hailed as one of the greatest solo debuts of the new millennium—a statement of purpose that introduced the North Carolina-bred singer-songwriter and his punky mix of folk, country and acoustic rock to the burgeoning hipster underground. But as critics and fans should have expected from a roots album that kicks off with a studio argument with David Rawlings about Morrissey, Adams can never be pigeonholed, even by his own recordings. Since releasing Heartbreaker in 2000, he has followed his muse past alt-country and into ragged rock-and-roll, Willie Nelson-approved country, power pop, black metal, manicured folky pop and even loving Taylor Swift covers—as well as an extended detour into cosmic psychedelic-Americana with his most collaborative backing band, The Cardinals.

Ryan Adams’ Heartbreaker is often hailed as one of the greatest solo debuts of the new millennium—a statement of purpose that introduced the North Carolina-bred singer-songwriter and his punky mix of folk, country and acoustic rock to the burgeoning hipster underground. But as critics and fans should have expected from a roots album that kicks off with a studio argument with David Rawlings about Morrissey, Adams can never be pigeonholed, even by his own recordings. Since releasing Heartbreaker in 2000, he has followed his muse past alt-country and into ragged rock-and-roll, Willie Nelson-approved country, power pop, black metal, manicured folky pop and even loving Taylor Swift covers—as well as an extended detour into cosmic psychedelic-Americana with his most collaborative backing band, The Cardinals.

“When I made Heartbreaker, I had just become of legal drinking age, which, if you ask anyone who knows me or knew me at the time, didn’t prevent me from partying before then— being a wild teenager playing metal and playing drums in punk-rock bands and having fun playing a lot of Sonic Youth-sounding music,” Adams says during a break from recording at his Los Angeles studio, where he is currently putting the final touches on a new album. “In the past, I didn’t know how to separate that this is my job. Although my whole heart is still in what I do because I love what I do, back then, I didn’t know that I could close the door at the end of the day. Now, I can shut down the shop, go home and watch Hill Street Blues and know the difference.”

Given his restless nature, Adams delivered perhaps his biggest surprise when he decided to revisit Heartbreaker, an album he’s described as a “mask” or “spiritual cold,” on his own PAX-AM label through Caroline Records and Universal Music. In addition to remastered tracks culled from Adams’ original tapes, the reissue also boasts demos, outtakes and a live DVD featuring his initial stab at Oasis’ “Wonderwall.” (Which was, in retrospect, perhaps the first hint that Adams’ record collection is far more wide-ranging than Gram Parsons albums.)

“Honestly, my part in it was remembering sessions or masters that had otherwise been forgotten because a lot of stuff went on around the making of this record, and this record was made several times in different kinds of ways,” Adams says of Heartbreaker, which was recorded in the wake of his seminal alt-country band Whiskeytown’s split. “It’s an interesting concept to go: ‘What the hell was I really doing after Whiskeytown?’”

You’ve never been particularly nostalgic when it comes to your music. Was there a reason you revisited Heartbreaker at this juncture of your career?

Heartbreaker was originally in a licensing deal with Bloodshot. Someone else was supposed to put it out, but I protested and said I really, definitely wanted it to come out on Bloodshot. My manager at the time was surprised by that. It was mainly because I really liked the people at Bloodshot—I liked what they had done and felt we had a kinship. Eventually, the licensing deal ran out and now I have my own label. It just made sense that we would do something special with it.

I had a pretty in-depth and long tour—and a lot of life madness—around Heartbreaker’s 15th anniversary in September, so it didn’t come out then. But this also took my day-to-day manager over a year and a half to bring together. That final Whiskeytown record didn’t have a tour because Geffen, my label, was dissolved into the Seagram’s deal. I didn’t really know how to get out of my contract, so there was some negotiating and some madness and some loss of songs. I had moved back to Jacksonville, N.C., where I was born, from New York.

There were a lot of changes involved in that process along the way. This was before I had a computer—I basically left a trail of recordings in my wake that, separately and together, my manager and I went looking for. Along the way, we unearthed a bunch of stuff that I don’t think either of us could have imagined we would have found.

It sounds like it was something of a scavenger hunt to remember what was going on during that time period and piece it back together. Listening back to those sessions, what struck you?

Well, those were different days for me, so it was a different process. People forget that I was just a teenager in Whiskeytown, and Whiskeytown really was a step away from the band I was in before, which really started as a combination of the things I was into, like The Feelies and Sonic Youth and the Yo La Tengo Fakebook record. I started Whiskeytown a year or two after my grandpa died. I left my hometown—that was a really huge part of who I was. Although I hadn’t had an affinity for [roots] music before, only a nostalgic feeling for it, it came back to me because that was the first music I was exposed to.

It’s like anyone who loses a parental figure, whether they are your actual biological parent or someone that raised you. You lose someone and then you instantly become drawn toward the things that made them who they were. For me, it was listening to country music and bluegrass music and, eventually, from there I went down the Bob Dylan folk-album canon. It reminded me of my grandfather—I had gone down that road as a child as well. Then I discovered Sleepy John Estes and Big Bill Broonzy and I followed that path.

Whiskeytown became a detour because, although I really wanted to be in a band, I used to sit and say, “I want to start a band that’s like the Cowboy Junkies and X and American Music Club all in one.” People in the band used to say, “But I thought you wanted to be like a Gram Parsons?,” and I’d go, “Well, we’re living in Raleigh, N.C., so the chances of playing it extraordinarily redneck and Southern just happened.” Even Corrosion of Conformity’s Eye for an Eye, that amazing hardcore album, still has some strange Southern wilt to it.

By the time the Whiskeytown dream started taking off, I realized that we didn’t have the technical ability to play that kind of music very well. We could write it and record it and hit the mark sometimes, but I had that proclivity to pick up the electric guitar because I was trying to change back into myself—who I was before that band. By the middle of all that, Whiskeytown was trying to maintain an identity that was separate from what I really was. That’s what happens when you get involved in an art project.

You’ve described Heartbreaker as a musical costume of sorts. Can you elaborate on that statement?

Although Whiskeytown was well meaning, it really did take a huge chunk of time and patience and learning and being steadfast to do it. The thing is, the dream imploded— and the band that I was in didn’t really cover the music that I totally loved to play. I moved to New York and my label went under, and my relationship went under right before I moved.

It was tremendously confusing and upsetting and debilitating. There was no one to play music with to express that. So, inevitably for me as a songwriter, I was looking to play guitar stuff that didn’t make me feel so damn lonely and that turned into music that sounded complete on an acoustic guitar. Whether it be a folk-sounding song or something that sounded more like a lament, I just got caught in that place.

It’s like having a spiritual cold—that’s not who you are, but it happened. I wanted it to pass so I could get out the door, spiritually speaking, and go skateboarding again and get out in the sun. That’s what I mean when I say it’s a bit of a mask. I was really trying to describe my pain in a dramatic way that did it justice, but I didn’t feel like I quite had the tools. Maybe that’s partly why people enjoy — there’s a naiveté there, like when you see a child trying to describe outer space. It’d be like watching me try to solder the connectors back on an electromechanical pinball machine. I can do it, but it’s going to be messy.

Though this album was recorded with that sense of singularity and loneliness, some familiar voices did contribute to the record, including Emmylou Harris, David Rawlings, Gillian Welch and Pat Sansone, who would go on to join Wilco.

That brings up a beautifully annoying thing. I didn’t really know what song publishing was in those days. I didn’t know what it meant to give up a half a song. I didn’t really collaborate with anyone on Heartbreaker. I wrote “To Be Young” a year before it was recorded and had already toured, playing that song solo in England. Dave and Gill came to the studio one day for four or five hours. They might have come again another day for a minute just to check in and say hi—we were friends back then and it was cool to hang with them, but really the whole record was just me and Ethan Johns. He played drums, I played acoustic and sang, and we played live. Ethan would typically play bass, and I would put an electric guitar down if it was needed but, often, we didn’t add much else. We wanted to keep it really stark. I didn’t want really any kind of steel—I wanted to keep things more like synth strings, so he brought a Chamberlin string machine.

The one day that Dave and Gill—who were Ethan’s friends—did come by, we had a really nice time and we hung out and came up with a couple of different arrangements for a couple of the songs. “To Be Young” was one of them. Then Emmylou came by and she had just gotten a bunch of pictures developed from the very first day of the very first Fallen Angels tour from their tour manager. He called himself the “Road Mangler”—he was the same guy that burned Gram’s body. So I sat next to her, and she was so cool and so chilled out, and we looked at these photographs. It was a real special, wild moment to be there with her.

Later on, Dave put “To Be Young” on his record, and I know he tells people, “I wrote this with Ryan.” He didn’t write any of that song. I really don’t want to burst anyone’s bubble, but I’d already written the song before I showed it to them. They showed me the G7 chord, which is the first chord on a couple of different Smiths songs. I didn’t know you could do the G7 chord, which is really beautiful, and I think they came up with these really cool harmonies for the bridge.

The way it went down later on is that, since I didn’t really know how publishing or any of that stuff worked, when someone went, “Well, here in Nashville, if someone works on a song, you just give them half— we need to do song splits.” I said, “Do whatever normally you would do.” Then, later on, it was credited as a co-write. That’s when I was like, “I really don’t want to live in Nashville anymore.”

That’s just how it goes there. I’m not saying anybody was trying to pull a fast one on me, but it’s always been weird for me later to hear: “Dave Rawlings wrote that song ‘To Be Young.’” I’ll be happy to pull out a demo from a year before he ever fucking heard that song.

Many of the songs on Heartbreaker remain in your repertoire. Given that you felt somewhat detached when you wrote them, how do you feel they fit in with the material you’ve written in subsequent years?

I prefer The Shining to The Cardinals when we go into our “exploration zone” with my older songs. I played almost all the guitar on Cold Roses, or sometimes J.P. Bowersock would do the second guitar and I would do the third guitar. I even played some of the bass and some of the drums. It was just the power of speedballs. The sound of that record was really Cat Popper on bass and me on guitar.

In songs like “Cold Roses” and “Magnolia Mountain,” I was trying to get this Tony Iommi-by-way-of-Garcia-by-way-of-I-can’t-play-guitar effect. There’s this amazing guitar player that a lot of people aren’t familiar with named Tara Key, and she’s in a band called Antietam, and they made a record called Burgoo. She had this guitar style that reminded me of some place in between Thurston Moore’s guitar vibe and Garcia or the Dorian scale. I was searching for that sweet spot where I could mess with that.

What’s interesting is that The Shining crept into learning these Heartbreaker songs and other songs from my career with a really soft approach. I love that [guitarist] Mike Viola and everybody really wanted to know what they meant. The rehearsals were a very beautiful process—literally, we were playing the songs and I would stop and go, “We’re covering this and I am, too, and let’s figure out why.”

We would sit and play for a minute and I would go, “Oh, man, this shit swings so much more.” We would reference the recording, and The Shining had taken what I was looking for so much further out. Nowadays, when we get into those sections, even when we play “To Be Young,” it’s way more rockabilly—way more greaser. It’s more Smiths meets Eddie and the Cruisers, which was always kind of my idea.

The other advantage of the newer band is that there’s no pedal steel. In The Cardinals, and I’ve seen some footage, they would always mute my guitar. The whole band was wearing in-ears, so none of them were listening to each other onstage—as soon as The Cardinals switched to in-ears, the band’s stage dynamic was forever gone. Really, the second Catherine Popper left The Cardinals, the band was gone, which is a shame because she really was the heart of the band. Brad [Pemberton] played “Cold Roses” with bundle sticks or brushes because he hit too hard—the only way we could keep it feeling like American Beauty was to try to cool him down. What’s different now is that Freddie Bokkenheuser, as a drummer, can go from the quietest guy to the most King Diamond, which is so ridiculous and fun.

As a band—and as a guitar player and singer—it makes me way less afraid to switch to an acoustic guitar to do a song like that, whereas, back in the day, I forced the issue more and more because I didn’t feel heard. I was trying to work my way into the overall sound. The Cardinals can be a big, noisy wall of sound. I used a lot of reverb and Neal Casal was pretty dry, so there wasn’t much of a blend. In The Shining, both Mike and I used Princeton Reverbs chained together. It makes all the difference—you can play within your own spectrum of sound, and we leave monitors onstage to just keep a little bit of the vocal going so we’re hyper aware of how much sound we have. We have these big, fake amplifiers, but there’s two Princetons inside of them. What’s cool about them is that they work as sound diffusers. It keeps the onstage sound from Freddie to the organ to the bass to our two guitars; it keeps it all in that little semicircle. It’s kind of the most amazing accident of all time. I suspect people have seen the pictures of Neil Young’s Rust Never Sleeps tour. I’ve always wondered if he ever went: “Oh, my god, it sounds so much better.”

The Heartbreaker reissue includes your first cover of Oasis’ “Wonderwall” from a show at New York’s Mercury Lounge in 2000. What inspired you to dig out that cover?

That’s one of the first solo shows I ever played. People were over that song by then, but I thought, “There’s more to this than anyone is even aware of.” So I dug it out, and people would typically do the thing that they used to do where they would laugh. But, by the end, they wouldn’t be laughing. I could push the envelope on the song. Much later on, I recorded “Wonderwall” for Love Is Hell because it fit into the interpersonal dialogue of that record. That record was very quietly about the time I lived in London. I was seeing someone who was English and, in England, you either like Blur or Oasis. They were like English football teams. The person I was dating was very much into Blur. When I ended up recording “Wonderwall” and making it much sadder and much more morose, it was because, as time went on, that reminded me of saying, “I’m telling you this is a really great song—you just have to listen to it completely broken down on an acoustic guitar.”

Of course, by the time I recorded it, it was me lamenting that funny exchange that I had. It was futile trying to convince someone who doesn’t like Oasis to like them. It’s like trying to convince someone who doesn’t like the Grateful Dead to listen to the Grateful Dead. They won’t fucking do it. There’s a preconceived notion in their mind.