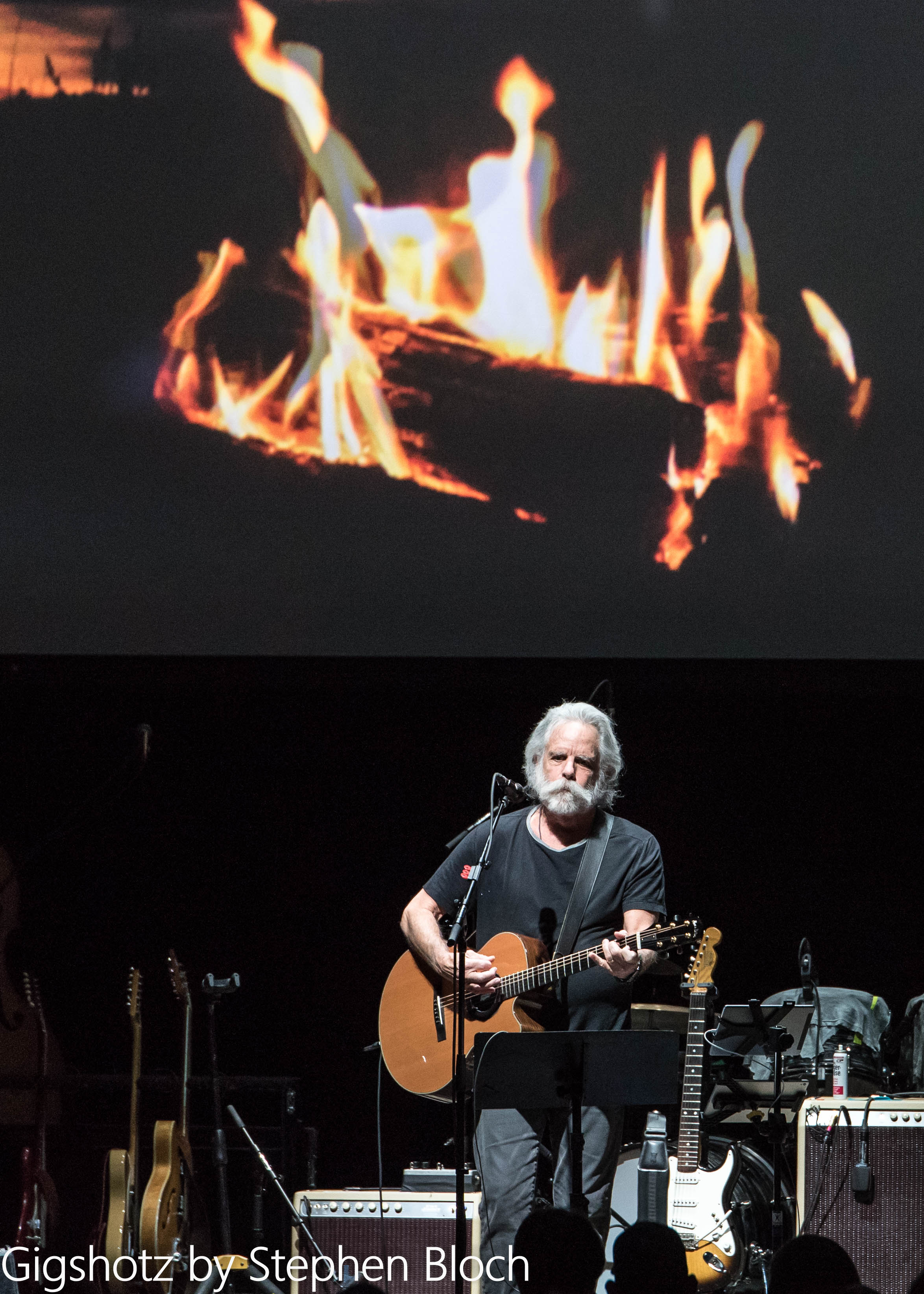

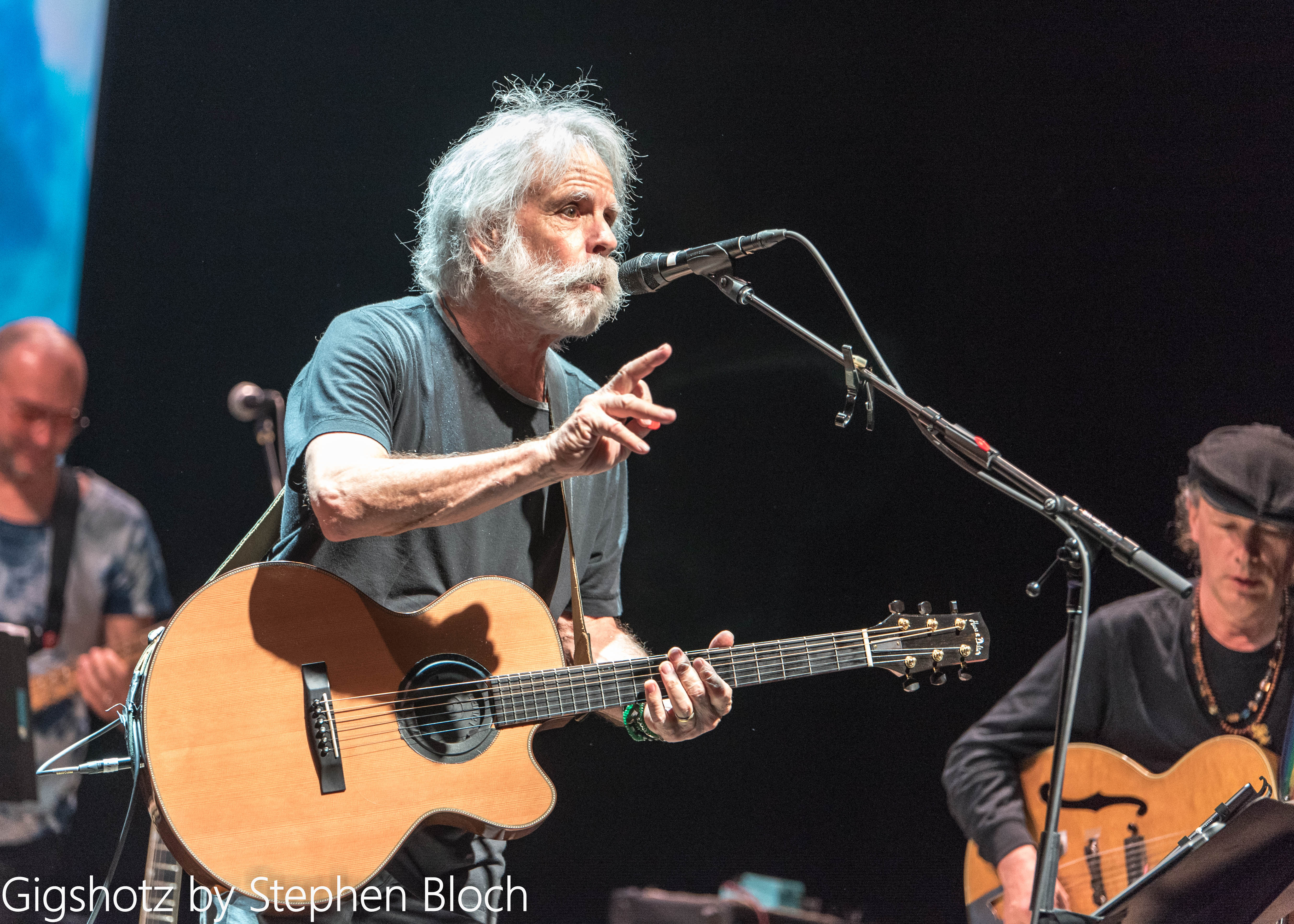

In Conversation: Bob Weir and Josh Ritter on Cowboy Songs and Forging an Unlikely Songwriting Bond

In March 2012, members of The National brought a supergroup’s worth of New York musicians to Bob Weir’s TRI Studios for a cross-genre HeadCount benefit dubbed “The Bridge Session.” In addition to nurturing The National’s own multi-volume tribute, Day of the Dead, the two-set performance, which heavily featured players from Brooklyn, N.Y.’s indie-rock community, introduced Weir to Yellowbirds’ Josh Kaufman, who served as the event’s musical director. A while after making that pilgrimage, Kaufman— a lifelong Deadhead who has gone on to produce prominent indie and modern folk acts like Craig Finn and Josh Ritter—encouraged Weir to revisit some of the fireside songs and cowpoke stories he learned while living on a ranch in his teens. Blue Mountain, Weir’s first studio album in over a decade and first collection of entirely original material in more than 30 years, is the result of their discussions and a spiritual successor to the cowboy songs he brought to the Grateful Dead, like “El Paso,” “Me & My Uncle” and “Mexicali Blues.” Weir cowrote Blue Mountain with Kaufman and Ritter, the album’s primary lyricist, and recorded the authentic country-western collection on both coasts, utilizing his regular RatDog family, Kaufman’s musical circle and other multigenerational roots ambassadors. Weir completed the record during a late-career renaissance that has included last year’s celebrated Fare Thee Well performances, the launch of Dead & Company, and myriad sit-ins and pop-up appearances. Shortly before the album’s October release on Columbia/Legacy, Weir and Ritter explored their new creative process during the following wide-ranging, freeform conversation.

In March 2012, members of The National brought a supergroup’s worth of New York musicians to Bob Weir’s TRI Studios for a cross-genre HeadCount benefit dubbed “The Bridge Session.” In addition to nurturing The National’s own multi-volume tribute, Day of the Dead, the two-set performance, which heavily featured players from Brooklyn, N.Y.’s indie-rock community, introduced Weir to Yellowbirds’ Josh Kaufman, who served as the event’s musical director. A while after making that pilgrimage, Kaufman— a lifelong Deadhead who has gone on to produce prominent indie and modern folk acts like Craig Finn and Josh Ritter—encouraged Weir to revisit some of the fireside songs and cowpoke stories he learned while living on a ranch in his teens. Blue Mountain, Weir’s first studio album in over a decade and first collection of entirely original material in more than 30 years, is the result of their discussions and a spiritual successor to the cowboy songs he brought to the Grateful Dead, like “El Paso,” “Me & My Uncle” and “Mexicali Blues.” Weir cowrote Blue Mountain with Kaufman and Ritter, the album’s primary lyricist, and recorded the authentic country-western collection on both coasts, utilizing his regular RatDog family, Kaufman’s musical circle and other multigenerational roots ambassadors. Weir completed the record during a late-career renaissance that has included last year’s celebrated Fare Thee Well performances, the launch of Dead & Company, and myriad sit-ins and pop-up appearances. Shortly before the album’s October release on Columbia/Legacy, Weir and Ritter explored their new creative process during the following wide-ranging, freeform conversation.

Bob, Blue Mountain’s roots actually predate the Grateful Dead, stretching back to when you spent time living at the Bar Cross Ranch in Wyoming. What led you to revisit those days with Josh Ritter?

BOB WEIR: The impetus to do this record came from two currents that flowed together, and, as you said, one got started back in the early ‘60s when I was working ranches as a kid and living in bunkhouses. My eyes were opened to a culture, which still existed that predated radio. It was a total oral culture and a rich one. And what the old cowpokes did at night—what they naturally fell into—was storytelling and songs. I was a kid with a guitar, so I learned to accompany those songs, and it was good ear-training because I had to intuit what the next chord was gonna be and when it was gonna arrive—or I was gonna suffer some abuse. That was something that stuck with me. Over the years, if a cowboy song came up and caught my ear for one reason or another, I might do it with the Grateful Dead simply because it seemed natural, whereas other folks wouldn’t have thought it was cool to do a song like “El Paso.” It was a little bit of an enigma to me and I felt I could breathe a little life into that stuff.

The second current happened after the show I did at my TRI Studios with a bunch of guys from Brooklyn. That crew was being wrangled by Josh Kaufman, and we worked well together and had a great time. I was amazed that I was able to play with that many guitarists and musicians without it becoming a cluttered mess. Everybody listened to each other and played appropriately. When they were playing, they were doing something that was relevant to what other people were playing, and that impressed me greatly because that’s where I live. When we were done everybody shook hands, slapped each other on the butts, hugged and then went back to their respective lives. But a year or two later, Josh Kaufman called out of the blue and said he was talking to some guys and had this notion to do a cowboy record, and that’s where I pass this off to Josh [Ritter].

JOSH RITTER: As I remember it, I was talking with Josh [Kaufman] at an airport. He called me about something else, and he was telling me how excited he was—that he had been talking to you about a project like this. And I said, “This is the most incredible thing I’ve heard, and what a great idea to make a record with these songs.” These old cowboy songs are a part of American history, deep in our bloodstream. The depth of experience living in them is so profound—and the chance to try and write something like those songs is something I would have given anything for. Without any hesitation, I begged Josh to let me try and send him a song to see if it sounded like what you guys had been talking about. I was on fire to try because I’m from Idaho, and we grew up with some of that mythology of the cowboys and loggers and all these mythic people. Even if this project didn’t work out, it would’ve started me down a whole new thing because it was just so exciting.

You both have experience arranging traditional American music for your own projects and using the American landscape as a reference point in your original material, but you come from different songwriting backgrounds. Josh tends to write on his own, while Bob, you have worked with a few steady songwriting collaborators over the years. Can you describe how your writing partnership developed during the course of this project?

WEIR: For me, a song gets written however it gets written. Sometimes, a shard of melody presents itself and I go around looking for a lyric to couple with that. Sometimes a lyric will come and I’ll put a melody to it or a musical texture to it. Sometimes, they both arrive at the same time, and sometimes something else happens. There’s no way for me to tell where a song comes from. They hide behind bushes; they jump at you from rocks up above your head. They land on you. They come through that window in the sky however they’re gonna come. It’s like cosmic waves—I have a feeling we’re being barraged by them all the time, and it’s just a matter of whether or not you’re open at a given moment to hearing that because, when a song comes to you, it’s coming from where you go when you’re dreaming, or where you are when you’re dreaming. I’m not sure you go there, or you just forget you’re there when you’re awake.

RITTER: I love that, and I totally agree with you. The most exciting thing about art, in general, is the excitement for the future and seeing what’s gonna happen, and seeing what songs are gonna come down the way—trying to stay open and open-minded about everything. This process was a real learning experience for me. I had not had the opportunity to work with someone who was so openminded before. Finding ideas freely, and then incorporating and adding such depth to them, was so exciting. And when we got to work together and we were trading ideas over the phone or over email, it was so gratifying to be able to work in such a cool, close way, knowing that we were working with ideas together. I just loved it; I learned so much about ways to work and be open. I’m trying to incorporate that approach into my life.

WEIR: I’ve had experiences with other people where certain characters show up in their dreams and in my dreams and, after we talk about it, we realize that they’re the same characters. I’ve been talking to a friend and said things like, “I had a strange dream last night. There was this guy that was really scary, but at the same time, profound” and he said, “Oh, you’re talking about this guy aren’t you?” The same guy had been in his dream. It’s beyond amazing, and I mean that in the truest sense I could possibly try to express. It’s beyond amazing what happens in that realm. We’re only just finger-tipping it, just getting the most cursory feel for that vast world. In that world, time doesn’t exist; space doesn’t exist. We can do anything. And that’s what art’s about—songwriting, in this particular case, and being able to share that with somebody. The deeper you go, the more profound it is. There’s something there, and I’m quite sure it was there before we were born, and it’ll exist after we die. Look at the words of Lennon and McCartney, for instance. Old John Boy, he’s not here anymore, but when those songs are sung, he’s alive. His window is open, and the character that came through him is here for us all to observe and to learn from and to feel and to know. It’s not often that you get a chance to meet somebody, as an artist where you just walk into a relationship like that. We didn’t walk in—we pulled our way in—but, nonetheless, I think we both had a strong feeling that the door was open for us. And we had walked through it before we even knew it. And we were in that other world.

RITTER: Sometimes, when you write, you have a chance to be an explorer, and when you really get going, you can find a whole new continent that nobody else has found, and it’s so fun—and that’s how I felt. Here, suddenly, all of these places that are so exciting to see in your mind actually exist, and you can write about them. It was so exciting to do that together. WEIR: We had only the slightest notion of where we were headed when we started crawling into this. I would imagine that we would both have in mind gunfire, dogs and stuff like that but, as it turned out, it became a more blue-collar deal. And then, on top of that, a good friend of mine was writing a book on the American quest and the frontier. He’s a historian as well as an anthropologist, and he has a number of Ph.D.s, and he found that cowboys didn’t have guns. None of that horseshit in the Westerns actually happened. None of it. Maybe there was a gunfight at the O.K. Corral, but it wasn’t just a bunch of guys with guns all in one place. They may have had a shotgun for a deer or bird, but it likely stayed in one of the chase vehicles—one of the wagons that would follow with provisions—and it was used for bringing down gangs. They had dogs for their predators. I didn’t even know this when we were finding our way into this album—this sort of blue-collar ethos that we discovered. It introduced itself to us. We didn’t go looking for it.

WEIR: We had only the slightest notion of where we were headed when we started crawling into this. I would imagine that we would both have in mind gunfire, dogs and stuff like that but, as it turned out, it became a more blue-collar deal. And then, on top of that, a good friend of mine was writing a book on the American quest and the frontier. He’s a historian as well as an anthropologist, and he has a number of Ph.D.s, and he found that cowboys didn’t have guns. None of that horseshit in the Westerns actually happened. None of it. Maybe there was a gunfight at the O.K. Corral, but it wasn’t just a bunch of guys with guns all in one place. They may have had a shotgun for a deer or bird, but it likely stayed in one of the chase vehicles—one of the wagons that would follow with provisions—and it was used for bringing down gangs. They had dogs for their predators. I didn’t even know this when we were finding our way into this album—this sort of blue-collar ethos that we discovered. It introduced itself to us. We didn’t go looking for it.

RITTER: When we first started, I was thinking a lot about Marty Robbins. It’s so exciting. But, like you say, that’s so interesting—that’s not the way it was.

WEIR: The western motif in the Dead came about because, when we first started off, we were all California boys—all Bay Area boys for that matter. Mickey [Hart] joined the band a few years in and he’s from New York, but the rest of us had grown up in the Bay Area. San Francisco was the capital city of the American West all through the Gold Rush era, the Barbary Coast era and well into the 20th century. So, culturally, it was all right there. If you watch the old TV western Have Gun – Will Travel, the character there had his office in San Francisco. So that tradition is just here—you can’t escape it.

When we moved out of San Francisco into Marin County, north of San Rafael, in the late ‘60s, we were in ranching country—Novato, Central Marin and those places. People wore cowboy hats in town because they were working and needed to keep the sun off their head. That was the California we grew up in. I already had a slight fascination with cowboy songs because I learned them and wasn’t gonna walk away from lessons that had damn near been beaten into me in the bunkhouse. If I understood and appreciated and felt like I could handle that aesthetic and presentation in a rock-and-roll band, then the guys would readily indulge me in that. And so they did.

Bob, you mentioned that these cowboy songs were reminiscent of a pre-radio oral tradition where ideas were openly traded and passed down between generations. Did that approach spur your interest in free, improvisational music?

WEIR: Well, in the bunkhouse, the guys weren’t sticklers saying, “This is how the song goes,” and if something happened and somebody had an ad-lib or a happy mistake and something new arose, that’s the way it went from then on. That process wasn’t free improv, certainly not by the Dead’s standards, but it was loose. At the age of 15, that was improv enough for me and, at a given time, for instance, I’m not sure that I got all the chord changes right on all the songs that would accompany “old boy singing,” but it was good enough for them. And, like I said, that was how the songs went for those guys after we were done doing them. I was the guy in the bunkhouse with a guitar, and if I wasn’t hitting the chords I was supposed to be hitting, then I was gonna get hit.

Josh, you have offered your own spin on folk, Americana and country since you recorded your first album while attending Oberlin. What was your entry point into the Dead’s music?

RITTER: I have a really profound memory, and it’s actually one of my most treasured memories and one that I get a little emotional about because it was so important. Several years ago, there was a sickness in my family, and I had to leave right from a tour to come home to Idaho. It was Fourth of July and I rented a car and it was a beautiful summer night. I was driving through Palouse, Idaho, and all the farmland there. It was a beautiful place—the wheat was really high, the sky was pink and I was driving home with the windows open. I could smell the onions in the air and all the different things you pass on the field. I had the Grateful Dead on and it struck me: The thing I feel I have consistently learned from that music is the power of the moment—the moment you’re listening, the moment you’re a part of it. It’s so strong and so engulfing that I don’t know if I have ever experienced that with any other music. That was my way in.

As Bob was saying, that moment in music when you’re all on the same page or you’re all figuring it out is so amazing. I’d say listening to the Dead and listening to those moments is as close to being with your friends making music as you can get. And so, I’d say that was my way in and a big moment for me. It’s like with cowboy music—it’s the repartee and the telling of the story, and just some of the hijinks that get you to those places that are so great. That relates to the Dead, too. I feel like there is something strongly connected between the Dead and the idea of a moment, where everything is feeling just right.

WEIR: I get some of those moments when I’m listening to Hank Williams. He’s a guy who takes me there. I also get some of those moments from John Coltrane, and there are certain writers in the American canon, or certain songs in the American canon, that take me there. And Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter are among those people. Maybe we’ll be able to count ourselves as part of that as well. There’s sort of an American Zen aesthetic in the arts and it’s very much so in music—and you know it when you hear it, and you know it when you see it. And we’ve had pretty good luck breaking into that.

Though he’s not featured on the album, John Perry Barlow, a longtime Dead lyricist, figures heavily into Blue Mountain’s story and you dedicate “Ki-Yi Bossie” to him. Before Barlow suffered a heart attack, you also originally hoped to have him and Gerrit Graham contribute to the album. Bob, can you talk about the time you spent with the Barlows back in your ranching days?

WEIR: John and his family opened that door and let me camp out in their bunkhouse for a summer or two, and then on down the line. In the later years, I actually bought into that ranch. But his health wasn’t up to the project, so he sort of gave us his blessing to take it where we would have gone. I wanted to have him involved, but it didn’t work out. Hopefully, he’ll pull through— he’s still having health problems—and we’ll bring him in on a future project. But we had his blessing, and that’s about as much as we can get from him. That, plus these were the kind of characters John could relate to.

RITTER: That’s great. “Ki-Yi Bossie” is such an amazing song, and to hear how that came about and how it fits into this whole record—while also bringing something totally new to the whole thing—was great. I love that song so much. I got a chance to see some of the recording sessions. In some ways, I felt it was important for me, and important for our writing process, to be there for some of that. And I’ll be honest: It’s intimidating to work with somebody like Bob. But I got to go and see them working in the studio one time and it was awesome. There were all these people in the room—some I knew, some I didn’t—from all from these bands that I respect and really love. To see everybody working in this way felt like this brand-new band forming. I have not played with a lot of different bands—I have my band—and to see this whole group of people all working together, it was great to see. It was so cool that Kaufman had this vision for the type of musicians that he thought would be really good.

Did you feel that the record’s nomadic recording process influenced the album’s overarching feel?

WEIR: For me, it didn’t matter where we recorded. It was a matter of giving each of the songs a chance to breathe with whoever we had on hand. Josh Kaufman would plug people into the project, and this song would go this way, and that song would go that way. We would just play with whoever we had, and they were masterful at covering the songs this way or that. I’d think to myself, “When I’m here, I’m playing to hear what somebody has to offer, and see how can I relate to that and how they’re gonna relate to what I just did.”

We had a new band every day, and Josh Kaufman was the magical factor that would put the glue in the groove. He knew these guys, he knew what to expect, he knew they were gonna work, he knew they were gonna plug in. And each day in the studio was a different deal: “OK, we’re gonna do this song and this song, and these are the guys we’re plugging in and we’ll just see what happens.” He’s a real good puppet master and, at the same time, he’s dancing on the end of the strings on some songs. It worked out real well for us and, generally speaking, that got the job done.

RITTER: I totally agree. There were some times when I was trying to figure out if Josh was trying to tell me something or not, and I kind of felt like, “I don’t know what you’re doing. I can’t figure it out, but it’s working.” Whatever it is you’re saying to me, it’s working.