Henry Hey on the Return of _Lazarus_ and Working with David Bowie

In 2012, producer Tony Visconti contacted Henry Hey and asked him if he was free to work on a studio project. Though he didn’t divulge any details, Visconti made it clear that this wasn’t a project to be passed on. Not long after, Hey was brought into The Magic Shop studio in New York City to work with none other than David Bowie, who wanted Hey to add some piano to a couple tracks on Bowie’s album The Next Day. This welcome surprise kicked off what would become a close working relationship between Bowie and Hey, who ended up being hand-picked to act as musical director on Bowie’s musical, Lazarus.

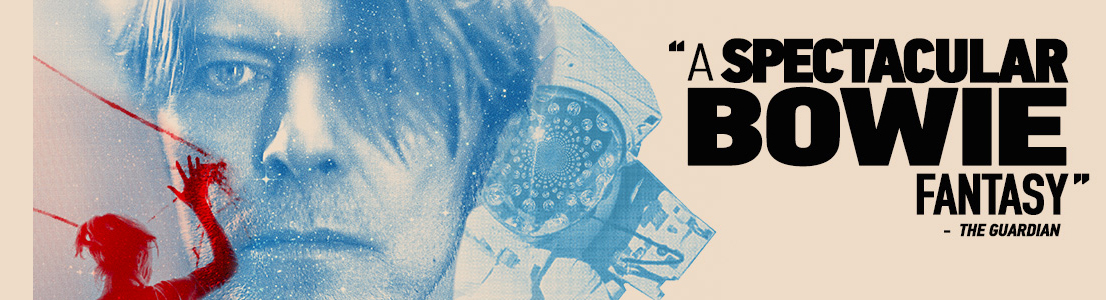

On May 2, Brooklyn’s Kings Theatre will host a special, one-night-only multimedia performance of Lazarus, which will pair a film of the musical taped during its run at London’s Kings Cross Theatre with a live performance from the original band from Lazarus’ first run in New York, including Hey himself. The musical takes after the 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth, which starred Bowie in the lead role and was itself based on the 1963 novel of the same name. Along with Bowie’s final album Blackstar—which featured lead track “Lazarus” from the musical—Lazarus was one of Bowie’s last artistic endeavors before he passed away in January 2016, but not before he was able to see a staging of his musical in person.

Before the event in Brooklyn, Hey spoke with Jambands.com about meeting Bowie, the professional relationship they formed, how Lazarus came to be and how he’s taken the lessons learned from working with a legend into his own artistic work.

The Lazarus film takes from the London performances of the musical. Was that one any different than the New York production?

That run was very similar to the New York one. In fact, I believe the intention was to keep the feeling similar to what happened in New York, but just in a considerably larger space. The stage is very beautiful, and the elaborate multi-camera filming in London and came out great. It looks really stellar, and they wanted to figure out the best way to show this film. They didn’t want to just put it out and say, “We’re releasing a DVD” or “We’re going to broadcast it.” This is what it became.

You were the musical director for Lazarus, and you played with the orchestra for the performances. Were you with them throughout both runs in New York and London?

Yeah, I was very lucky to work with David directly in the development of the music and arrangements for this, and then I lead the band in New York and started the band in London. So I didn’t stay with production beyond opening night, but I did start that from the very beginnings of the development in London and took it through opening night.

To get a background on how the Lazarus project came to be, let’s go back to when you first collaborated with David. You two first met when you came on for his album The Next Day, right?

That’s right. Well, the first sessions that I did for David was actually on the single “Where Are We Now?,” and I played piano and some keyboards. [Producer] Tony Visconti, someone who I had worked with, brought me into the session and it was very secret, as was the case for a lot of these in David’s world, especially at that time. The only indication was when Tony said, “Are you available these dates? You’re gonna wanna be available. It’s a good project.” That was it. Then I showed up, there was David Bowie and off we went.

So you didn’t know it was a David Bowie project until you literally got into the studio and saw him there?

No, I didn’t. That’s right. Well, nobody knew because nobody knew about that record. I don’t know if you recall what a surprise that record was, because David hadn’t been recording. So we recorded and then we had to keep the secret for another year. For a year! I mean, there were only a handful of people who knew.

So what were you telling people that you were working on, if anyone asked?

I didn’t tell people. I didn’t tell anybody—I couldn’t. It was at the Magic Shop, which was not a high-traffic studio, so it wasn’t a situation where I’d encounter a lot of people that I knew going in and out of the studio.

Anyway, I played on that track and then I ended up coming back to plan something else and then David asked for me back directly. He requested me by name for some other thing, and I feel like we developed a good rapport and we had an easy time in the studio together. After the record was finished and we had done some extended tracks together on that record, he reached out to me via his manager, who said, “Can you come to the office? I wanna talk to you about something.” So I came to the office, and he said, “David has this piece that he’s developing and he feels that you’re the guy to do this job.” I was floored. Obviously, practically before his manager finished the sentence, I was saying, “Yes.” I was elated to be involved in anything that David was doing. Then we had conversations about the concept of the piece and we started developing rough sketches of the arrangements for what would be the workshop—we had a workshop in Midtown, as is common with a lot of plays and Broadway stuff. And then the following year, we started working on the actual stuff for the play and away we went. We worked through the year in 2015 and then it opened in the fall of 2015.

Pretty quick turn around.

Yeah it was very quick. You know, because these things can take years sometimes, but everybody was working quickly and David was really excited, so we got it up and running.

Obviously you guys built a good relationship, but what were some of your first impressions, especially after you walked into the studio and realized you’d be working on a David Bowie?

Well of course if you saw somebody like a David Bowie in the studio, your first reaction would be like, “Oh my god, I’m in the presence of David Bowie and I’m freaking out.” Personally, he didn’t want that, and he was very, very disarming. He put people at ease right away. He was relaxed, humble and generous and he just wanted to make music, so there were no airs there, no feeling of superiority. It was unlike a lot of situations that I’ve been in with high-end artists because some of them can be very standoffish. He wasn’t distant at all. He made it very easy to have a creative space, and I got that impression from the very beginning—but especially the more I worked with him. It was a great thing that he did, because it put people at ease and it really brought out their best work.

That’s good to hear. Did you work on any other studio stuff with David?

No, I didn’t, just The Next Day and extended tracks for the record. There was an ancillary track I played on as well that ended up in a commercial, actually, and it might have ended up on the extended tracks, but it was at the same period. And I’m really thankful that I got to work on that record, in hindsight. Of course, I wish that my work with David had been years and years prior as well, because it was such an incredible experience.

When you and David and Enda Walsh first started working on Lazarus, did he have a fleshed-out idea of what songs he wanted to include in the show?

Actually, David gave Enda a list of songs and Enda chose the songs. There was some back and forth about a couple songs, but mostly he allowed Enda to choose the songs as it fit the piece. David was very adamant about that—he wanted the music to serve the piece and not the other way around. He didn’t want this to be a jukebox musical or a showcase for songs. He wanted it to be an art piece that framed the story of Thomas Newton [Lazarus’ main character], and the music would be adapted to that. You know, so many artists have done musicals and plays where it’s really a rough sketch based around the songs, and the songs are the payoff. David absolutely didn’t want that. He was very, very clear about that.

David was in the movie The Man Who Fell to Earth back in 1976, so this must have been something he was thinking about for a while. Do you think that this show was kind of a passion project long in the making?

The story that I understand is that he had always wanted to make a musical, for most of his life. In fact, I think that his relationship with Robert Fox really helped to make that possible—Robert Fox being a very powerful and passionate producer of these shows, one of the production partners in both the New York and London productions. But yeah, David always wanted to do that, but it’s not always so easily done, at least effectively. I think the time was right for this, and obviously it goes without saying that I think David was on a timeline, in the end, but I think it’s great that he got to do it and it’s great that he go to see it in his lifetime.

I’ve read that some people who were working on his last album Blackstar with him didn’t know that he was sick, or at least the extent. What was your experience with that?

I mean, we didn’t talk about a timeline, and obviously the few of us who were working closely with him had to know he was sick. But the only reason we needed to know was so that we could work with him every day and be aware, but we didn’t talk about a timeline; we didn’t talk about an urgency to finish. I think it was just an excitement to work on it, and I think that it was mostly just serendipitous that we finished and he could get to see it. And he was so excited to work on all his creative projects, both Blackstar and Lazarus, and he just wanted to work for all the time that he had left, you know? He was passionate about working on it, and I don’t think that he had any conception of how long he would have. He was mostly just interested in the work.

Back to your part in this musical—did you pick the musicians that would be playing the songs yourself?

Yeah, I picked musicians and talked to David about them ,and David was very interested to know about every musician. He individually approved every musician. He looked at them and he looked at YouTube videos, and we talked about the musicians and why they were right for it—he wanted that to be right. Obviously it’s the care of his music, and he wanted the musicians to have a certain spirit. By the same token, he was very happy to have new musicians that he hadn’t worked with, you know. In fact I remember his quote saying, “Yeah, new blood.” He says he was constantly looking for new things, that he was curious and was inspired by new musicians’ takes on his music, which was really fantastic to see. I tried to pick people that I thought would respect his music and deliver it in an authentic way.

So he was very hands-on with the planning and production of it.

He was, he was. And obviously there was a big team of people working on this, but he was engaged in a lot of it. It was a busy time-frame between Black Star and Lazarus.

Had you done this sort of thing before, leading the musical direction for a musical?

Not for a musical. I’d done a lot of musical directing at this point, but not for a musical, so it was interesting. It wasn’t so foreign, because I’d written music for picture and I’d done a lot of pop-musical directing and producing. So it just felt like the pieces were coming together, but there were some things about theater that I had to quickly learn. Thankful to some patient people that I was working with, I learned them. [Laughs.]

What were some of the stumbling blocks that you came across?

I don’t think they were so much stumbling blocks, it was just some of the process I had to learn. It was mostly people saying, “Well, no, we can’t do that; we can do this,” and explaining the process once we got in the theater and how the times worked. But the music part was not at all foreign. The music part was very clear to me, and I guess I’m very lucky because I had a lot of license, because I basically had David’s say-so. I’m sure it was a little alarming to some of the people in the production, because you know, the music got a lot of attention—as it should have, because it was David’s music—and we spent a lot of time getting the mix right in the theater, both in New York and London. Maybe more time than might be spent in other productions, but I feel like it worked out well, and I feel like in the end everybody was happy with it.

Did you feel that, in the end, you struck the right balance between highlighting the great songs while still staying true to David’s idea of Lazarus a full, standalone piece of art?

I do, I do. And I think he was really happy with it. We treated some songs very, very differently. In fact, you know, there were some London “fans” who I remember came to the musical, not many of them, but a couple of them who ignorantly said, “Oh, this is terrible. David would have never liked this.”

There’s always going to be those people.

Yeah, because some of the treatments were so different, and David asked for them specifically to be different. So yes, I think we accomplished it, because the songs frame the piece and they’re designed to set up certain scenes. You have really recognizable songs that have a completely different approach because they have to set a mood and function in a way they never did before.

In preparation for this May 2 performance, have you been working with the musicians?

Fortunately, they’re all really fantastic musicians, some of the best musicians in New York, if not the world. I knew that from the beginning, but especially now. It will be nothing for them to get the show back to where it was. And they also played it 75 times in New York. So it’s not going to be foreign. They’re all reviewing, they all have the scores, and we’re getting together very soon to start working on the music together again, so the band is going to be in top shape.

Have you worked with any of the musicians since you last played with them for Lazarus?

Definitely. I work with Chris McQueen, the guitarist, quite a bit. We have an instrumental band and we’ve done a lot of touring together. Brian Delaney, the drummer, is one of my oldest friends in New York, and he’s just finishing a tour in Australia and New Zealand with Melissa Etheridge, but I see him often and we’ve done a bunch of recording. JJ Appleton, the second guitarist, is not only a great guitarist but a great producer and songwriter, and we’ve worked on several things including some songs together. So those guys are active and I see them relatively often, and I’m happy to know them and call them friends.

What sort of things did you learn while working with David in the studio and on Lazarus that have translated to your personal work and working with other artists?

Well the most important thing that I learned from David, something that was a life-changer for me—and he talked about this in interviews—is the idea doing your best work and not working for other people. And when he says that he doesn’t mean not working on other people’s projects; he means not doing what other people think you should do in your own art. I’ve really taken that to heart, and I’m trying really hard every day to make that a top priority with my music and with things that I do. And it helps me to strive to be better, to be creative, and to think artistically with the time that I have. The older I get, the more I realize that—obviously this goes with saying—our time is finite. He really helped me to realize that this stuff is important, that I want to create art as a musician and that the reason that I got into music in the first place was to create, to experience the joy, to share the joy of music and art. It’s so easy if you’re an able musician and you have a skillset, to get caught up in just working on things for people. And you can spend a lot of your time doing that and that’s great—and everybody needs to pay their bills—but I also now feel a renewed desire and drive to create more, to be a fertile artist in my own right, so I’m working on several personal projects. Like I said, I have this instrumental band, which is original compositions, and we’ve been touring and working harder on that than ever. And I’m producing a record for a known artist which I can’t talk about yet, but that’s coming out later this year. Those are my creative projects, and they’ve become more important to me.

What should people know about the May 2 performance of Lazarus?

I think that even anybody who saw it in New York or London will have an opportunity to see it in a way that you might never see it in a theater production because of the way the filming was put together. It’s dramatic. You can see a lot in the characters, because you see them up-close in a way you couldn’t see unless you’re standing in front of Michael C. Hall, and the characters are vivid and the jump off the screen. The other thing is that if you see this film, you’re going to have questions, because it’s not a traditional piece, and I think that by its art, it’s designed to raise questions, and that’s fine. It’s okay to have questions, and it’s okay to not understand at all the many, many layers to it. I think it’s a beautiful thing.