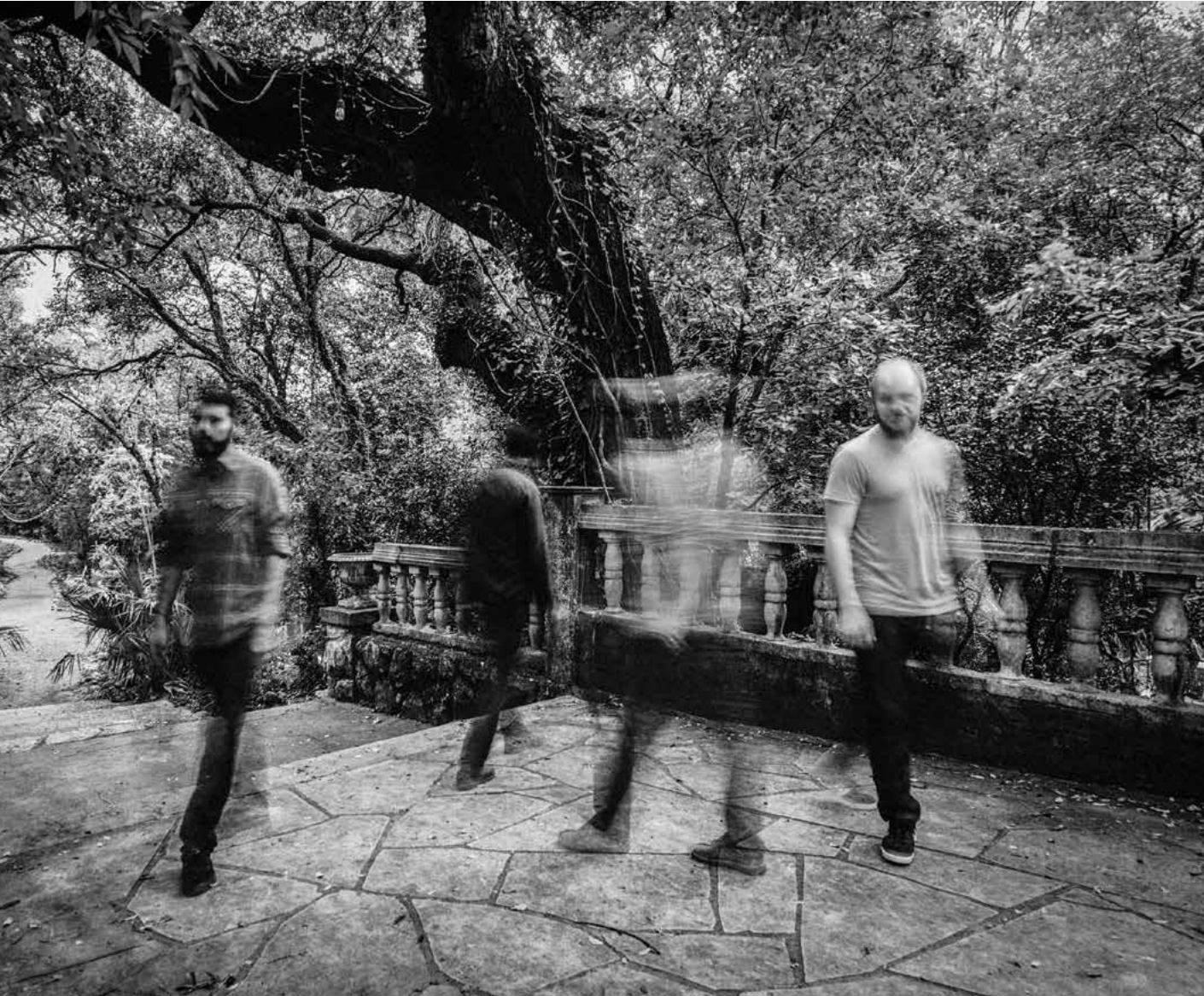

Explosions in the Sky: Explosions in the Wilderness

Change may not be an inevitability, but it can be a necessity. It erases the complacency that can build over time, undoes the instinct to continue with something down a path simply because it is familiar, and alters the possible future narrative. Three years ago, as Explosions in the Sky began writing their seventh studio album, The Wilderness, the four musicians determined that change should be invited into their process.

“We have written songs the same way for 15 years,” Explosions guitarist and bassist Michael James admits. “We’ve been a band for so long, and the way we’ve approached songwriting as a band was very much like, ‘Each song needs to be its own story, its own three-act narrative, in a way.’ It seemed like we’d done that for so long and there are so many different ways to write songs, and we were interested in exploring the ways.”

“We always think, each time we make a record, [that] it’s way different than anything we’ve done in the past,” adds drummer Chris Hrasky. “And then people say, ‘Yeah, sounds like you guys.’ And we’re like, ‘Goddamnit!’ And then, a year later, we do it again. It’s cool, but then maybe we’ve beaten this dead horse a little too much. So that was the idea: We wanted to erase as many of our default settings as possible but still make songs that we like.”

When Explosions in the Sky formed in Austin in 1999, the intention was to create instrumental rock music that was engaging and that revealed self-contained stories in each track (which have often been reflected by the group’s poetic song titles). Their 2000 debut, How Strange, Innocence, set the stage for the career to come, and featured extended soundscapes, none of which were shorter than five minutes. For the band, composed of Hrasky, James and guitarists Munaf Rayani and Mark Smith, the music was a way of exploring emotion without words, of explaining a sensibility using only a combination of instrumental sounds. Since then, Explosions’ career has been founded on those ideas, and by the time they released their last album, 2011’s Take Care, Take Care, Take Care the band had developed a sizable enough fanbase to land at No. 16 on the Billboard Top 200.

But in 2012, as the musicians wrapped two film soundtracks (for Prince Avalanche and Lone Survivor) and began to slowly discuss how to proceed with their next album, there was an overwhelming sense that something needed to shift. “The grand idea was, more than ever, to not rewrite any song,” Rayani explains. “Not note for note—we wouldn’t do that—but not rewrite any song, in terms of tone, the way we have before. The idea was to really expand our way of thinking [and] maybe take some left turns when we were known to take a right turn. So I feel it’s more of a real evolution. All of a sudden, we sprouted a new arm.”

“We’ve written a lot of music, and it just became really obvious that if we were going to continue to write music in the same way, with the same artistic goals, we were going to lose interest,” James adds. “We didn’t want to lose interest. We didn’t want to be bored by this.”

The Wilderness, which didn’t find its title until far later in the process, began as a pile of ideas, all partially formed and uncertain. There were a lot of arguments and conversations as the musicians sorted through that pile. It was a challenge to let go of old habits and allow new methods to sift in. Breaking muscle memories, it turns out, is not the easiest of tasks.

“To break those habits is a bit difficult because you are who you are, no matter how hard you want to be someone else,” Rayani says, noting that one simple way of shifting the process is playing a part on a different instrument than one would typically select. “It feels forced in some moments. Whenever that would show up, where we would purposefully try not to be who we are, then that would draw some pause. But in other moments, when the idea was just to be something different and rely on our different strengths, it was pretty captivating. And that shows up quite often on this record.” He adds, “When you step back and look at the painting, you can see it was done by our hand, but it comes with a new array of colors. It comes with a new stroke, a new approach.”

Smith admits that the writing process resulted in “more arguments and discussions and hand-wringing than during any other album,” but in the end, there were also “many more moments of, ‘Wow, I am so thankful we found each other.’” It’s evidence of what has kept Explosions together and productive for so many years. For the four musicians, who Smith says “complete” each other, tackling this new aesthetic was best done in tandem.

“It was extremely challenging,” James says. “At first, we didn’t know that we wanted the record to sound like, and we didn’t all agree on what being experimental in this kind of writing process was going to entail. We’re all extremely good friends and extremely good collaborators—and have been for a very long time—but we all have our own very strong opinions. It took a long time of us getting on the same page of what this album was going to be. We spent about two years arguing and one year actually making it. But it was so worth it.”

One of the notable shifts on The Wilderness is the length of the songs. Explosions’ surging instrumental tones, which evocatively balance sonic and emotional highs and lows, still line up with their recognizable style, but they are terser and more compact. This time, each track doesn’t necessarily tell its own lengthy tale—which is something very intentional on the part of the band. The nine songs are statements, but they are not all grandiose statements. Instead, they come together to uncover a singular album identity. That thematic idea, reflected by the title, is nebulous, open to interpretation, and each band member tells it slightly differently. For James, the idea of “the wilderness” is about uncharted territory both outward and inward. It’s as much about outer space and its unknowable expanse as it is about the depths of the human mind.

“It all started with us watching the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey way too many times,” James notes. “That’s been one of our favorite movies forever. That’s kind of where that movie gets its power— with the expansive nature of outer space, coupled with the idea of the human personality and the dichotomy between the two.”

As with the band’s prior album, the names of the songs offer clues as to their intentions. The titles, which Explosions conceive as a band, are not essential, but they do send the listener in the best direction of understanding the songs’ meanings. “They help just as a point of reference, as a dot on a map,” Rayani admits. “‘You are here.’ Not having that ‘You are here’ dot on the map—it’s still an intriguing map to be on. Since we play instrumental music, something we are very lucky about is that our music is language-less. It’s about how you interpret it. That offers great flexibility and an expansive area of absorption. So the song titles have meaning, but they are not the meaning.”

“When you listen to ‘Colors in Space,’ maybe think about the ‘Star Gate’ color sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey,” Smith elaborates. “That’s what we watched when writing the whole ending part. When you listen to ‘Tangle Formations,’ maybe it would be cool to know that the title refers to the way memories are stored in the brain and the way they change during the onset of Alzheimer’s. ‘Logic of a Dream’ refers to the way the four very disparate sections of that song strangely lead to one another, yet make a weird sort of sense.”

The second major change on The Wilderness is how the album was recorded. In the past, Explosions has recorded their albums in almost the same way they would play them live, the songs easily recreatable onstage. But at first it wasn’t possible to play The Wilderness live because it incorporates so many new elements and new instruments. The band spent two weeks in the studio in July of 2015, which was the longest they’ve ever spent crafting an LP (the band’s first two albums were laid down in a mere two days). They recorded in Dallas with John Congleton, who has engineered several of Explosions’ albums and who had a much stronger voice in the process this time around. The highs and lows of the music feel different, and the familiarity of the band’s sound is augmented by unfamiliar notes, ones that introduce a wholly alien feeling.

“I hope this album hits some of the emotional nerve centers as our previous albums, but the fact that we’re doing it without the big, distorted crescendos and lilting arpeggios and big, searing payoff melodies means that those nerve endings don’t feel quite the same,” Smith says. “Sometimes I listen to this album and I don’t quite know what I’m feeling or what is causing me to feel moved. But the important thing is that I am feeling moved. It’s a more emotionally ambiguous album, and that appeals to me greatly because it seems to capture more of what I feel after living 40 years of life. There is not so much of a narrow focus on ‘sad’ and ‘triumphant’ as there is a shifting color spectrum of sense and experience.”

Now, as Explosions prepares to go out on tour in support of The Wilderness, there is the discussion of how these songs will be translated onstage and where they will fit in with the sounds from previous albums. It’s yet another challenge for a group in the midst of change. (“I am already looking forward to dozens of hilarious technical problems during shows,” Smith notes.) The group is exploring new visuals to accompany them onstage, which may mark a drastic shift from their notably sparse live shows. It’s an ongoing experiment, one that has truly breathed new life into the quartet.

“The harder you have to work for something, the more satisfying it is when you’re done,” James says. “When we were finished with this album, we were all very happy with it. It was exactly the album we all wanted it to be. And whether or not that means it’s any good is beside the point. We worked so hard at it and it’s something very specific, and we did push ourselves a lot and we pushed each other a lot. To have that very difficult process be what we considered a success was extremely satisfying.” He adds: “It’s certainly the most interesting thing we’ve done in the context of our career.”

Is there a fear of the possible response to change? Does the band worry that the world tends to resist it, especially when fans are satisfied with—and even in love with—the status quo? “I don’t know if people are going to like it or not,” Hrasky considers. “I don’t know if people who liked The Earth Is Not a Cold Dead Place are going to be interested in this record because it doesn’t do the same things.”

He pauses, carefully considering his words. “I do hope that at least people recognize that we’re trying something different,” the drummer continues. “If people hate it, I can accept that. But I’ll be really bummed if they go, ‘Yeah, this just sounds like another Explosions record.’ To me, creatively, it feels like a new thing and makes me excited about what we might do next. Maybe, in two years, we’ll have some other dumb idea in mind and start over from scratch again.”