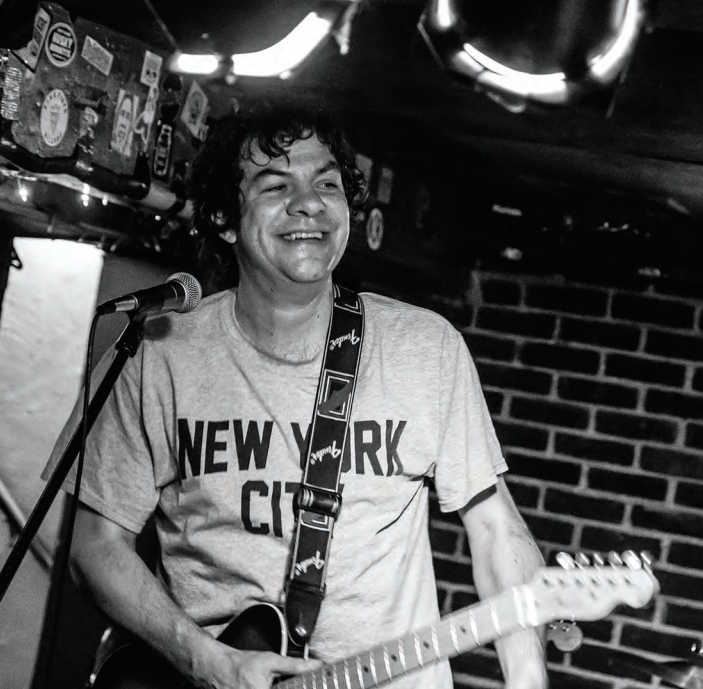

Dean Ween: What Deaner Was Talkin’ About

Over three decades after forming his oddball alt-rock duo, Mickey Melchiondo is in the midst of a creative renaissance. The guitarist, better known as Dean Ween, has spent the past eight months on a fervently anticipated reunion tour with Ween, released a solo album—the first of his career—and is experiencing what he says is the most creatively fertile songwriting period of his life.

Over three decades after forming his oddball alt-rock duo, Mickey Melchiondo is in the midst of a creative renaissance. The guitarist, better known as Dean Ween, has spent the past eight months on a fervently anticipated reunion tour with Ween, released a solo album—the first of his career—and is experiencing what he says is the most creatively fertile songwriting period of his life.

“I hold myself to this ethic of a song a day, and I do it, like Prince did or Neil Young—the people I really admire the most, respect the most and whose music I love the most— that’s where I’m at right now,” says Melchiondo, who, even as he speaks from his home in New Hope, Pa., is preparing for a busy night at his weekly jam session at a local venue, and perhaps even some recording time with the same musicians he’ll be playing with. “I go to the studio every day, pretty much all day. If I have no ideas, I work on something I did yesterday to improve it. I’ve gotten used to it, and I love it. It’s very liberating.”

It took him some time to get to this point, however, starting when Ween began what turned into a four-year hiatus in 2012. After working with longtime friend and collaborator Aaron Freeman, aka Gene Ween, since the mid-‘80s, there was a bit of a learning curve when Melchiondo was embarking on this new, solo chapter of his career. “There was so much going on in my head. I had to figure out where I was gonna go—if I even wanted to be a musician anymore,” says Melchiondo, who also pursued a parallel career as a fisherman. “I’m so used to having the best creative partner in the world in Aaron. He would have an idea, or I would have an idea, or we’d both have an idea—or we’d have no idea. All the best Ween songs were written by both me and Aaron together.”

Lacking his usual songwriting sounding board, Melchiondo turned to his coterie of musical friends, including the other members of Ween—bassist Dave Dreiwitz, drummer Claude Coleman Jr. and keyboardist Glenn McClelland—who all currently tour with Melchiondo as the Dean Ween Group.

“He’s in a productive phase of writing and recording,” Dreiwitz says of Melchiondo. “He’s playing all the time, probably more than he has in the past—having a guitar in his hands for more hours a day than he might have before. He’s having fun with it, and that’s the most important thing.”

That’s not to say that Melchiondo wasn’t having fun previously, and he’s the first to explain that his solo effort aren’t the typical, yearning-to-do-my-own-thing kind of outlet that many songwriters in bands experience. “Ween pretty much satisfied my every need,” he says. “Definitely not constraining band to be in—I’ll never make that claim. It wasn’t like there was a part of my soul that wasn’t represented on a Ween record. If we wanted to play fast, slow, country or metal, it was always there as an outlet.”

But, after constructing a new studio to further his creative endeavors, Melchiondo began to consider doing a record that would be solely his, and the question arose: What’s the purpose of a collection of non-Ween Dean Ween tunes? “I really started to think, ‘If I’m going to make my own record, what do I want to get out of it?’” Melchiondo says. The answer came to him quickly: The album would reflect his renewed focus on the guitar, which, he says almost reticently, has slowly become his main musical outlet.

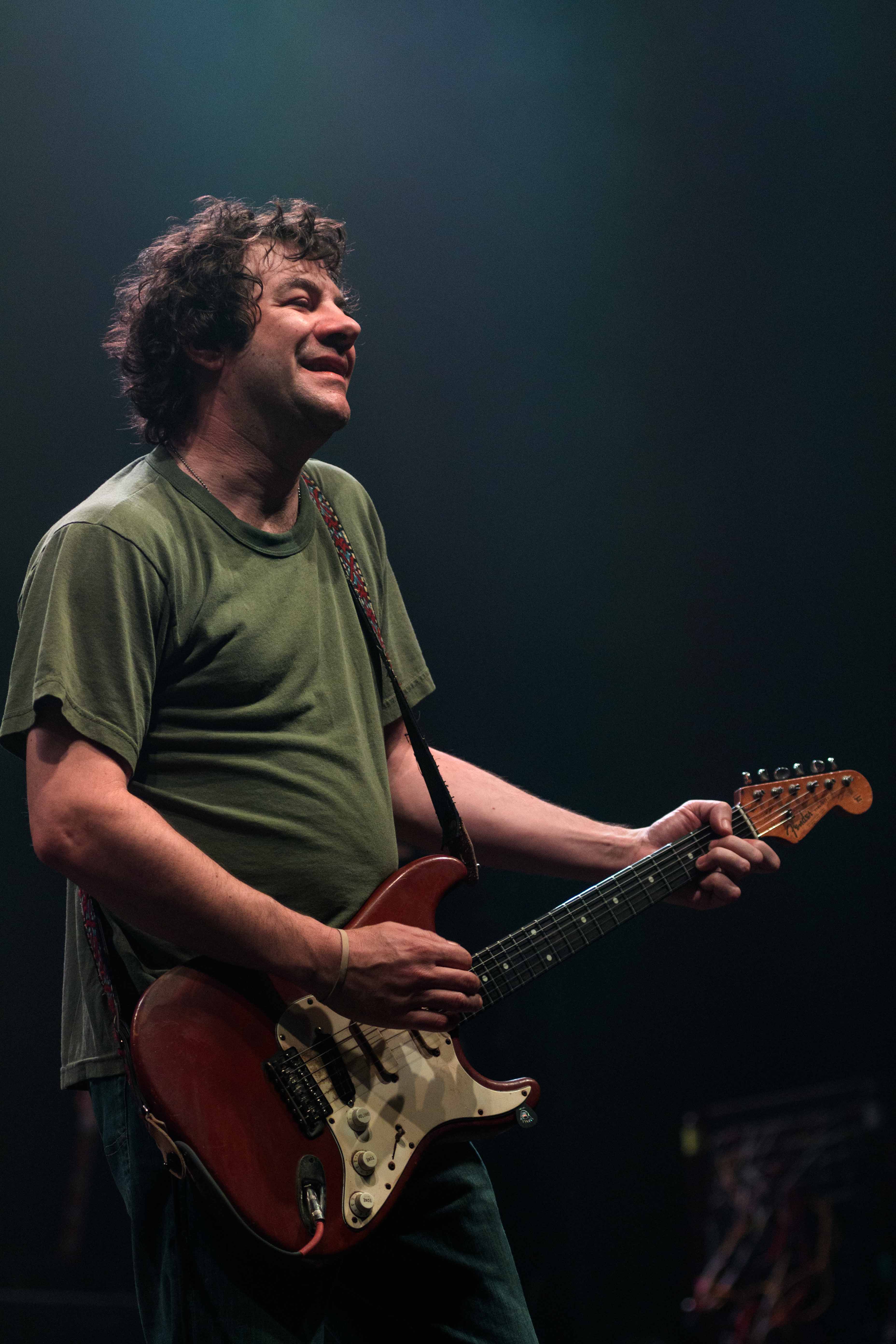

“I have, over the years, become a guitar player,” Melchiondo admits, the sense of deep, personal struggle apparent in his phrasings. “In Ween, we wear so many hats— I’m the drummer, I’m the guitar player, I’m the bass player, I’m the keyboard player—and so is Aaron. [For this,] I decided to really focus on my guitar.

“And songs, of course,” he adds, making it clear that he didn’t want the album to be too focused on guitar. “There’s nothing more important than the song. When you think of guitar only as a guitarist, you think, ‘What is compelling to listen to that only guitarists are going to listen to?’ I don’t like that kind of shit. Unless you’re so good that you can do that— like Jeff Beck or something. I’m into songwriting, so I wanted to bring that to the front. It’s all songs, not wanking guitar shit.”

The album, appropriately titled The Deaner Album, accomplishes both goals— some tracks tilt toward guitar-heavy romps, while others are more song-oriented—collecting 14 eclectic numbers that range from brash to understated, from jaunty to earnest, resulting in what Dreiwitz calls both “a guitar party” and “a funky good time.”

“They say you have your whole life to make your fir t record,” Melchiondo says. “And even though I’ve been doing this since ‘84, I’ve had my whole life to make The Deaner Album. So, to me, it’s like a compilation, in a way.” He adds that the themes of the record tend to center around “self-loathing and righteousness at the same time—that’s something we’ve kind of always done.”

Although he’s now writing mostly by himself, Melchiondo has not drastically changed his creative approach from what he did with Ween. “I’m in my bedroom right now, looking at scraps of paper with song titles, chord progressions, some lyrics that I may have written three years ago,” he says. “And some of it’s brand new and the whole thing is written in five minutes from start to finish. t all gets represented, in time. But I have so much to draw upon. Life is the most inspiring thing—more than music, more than other people’s music.”

There are, however, nods to other people’s music within The Deaner Album’s songs. Opening track “Dickie Betts,” an instrumental romp in the style of the Allman Brothers Band, deliberately wears its intention on its sleeve. “A lot of jazz artists—Miles Davis in particular—would make an homage to somebody—playing in that mode or that style—and they would call it that. Like, ‘Billy Preston,’” Melchiondo explains. “Miles Davis has a million. So I was trying to come up with a title for it, and what I’m trying to do here is really obvious—I’m trying to do the Allman Brothers thing, without stealing anything directly. It’s the perfect title—there it is. So no one can go, like, ‘Oh, this song sounds like a rip-off of the Allman Brothers.’ It is, dumbass! It’s a tribute!”

Another tribute comes in the final track, a cover of Funkadelic’s “Promentalshitbackwashpsychosis Enema Squad (The Doo Doo Chasers),” sans George Clinton’s scatological voiceover. Melchiondo calls the song a “bottom-of-the-ninth addition,” which came about when his friend, and Funkadelic guitarist, Michael Hampton, who played on the original One Nation Under a Groove cut, happened to be in the studio. The song was also part of the Dean Ween Group’s unofficial Funkadelic tribute show earlier this year. They were set to play with keyboardist Bernie Worrell, but the funk icon was unable to make it to the performance due to his ongoing battle with lung cancer. Worrell passed away just days after the show. “It was going to be his last gig, if he could make it, but he was too sick,” Melchiondo says. Worrell, who hailed “right up the road” from where Melchiondo grew up and still lives, guested with Ween at Berkeley’s Greek Theatre in 2003. “I knew Bernie and played with him, and having Michael was huge, so we put a bunch of P-Funk covers in there so, if he did show up, he could sit-in with us. But, sadly, he didn’t make it.”

Melchiondo is clearly enjoying the third act of his career. Ween reunited for three sold-out shows at Broomfield Colo.’s 1stBank Center in February and is currently in the midst of a cross-country sweep that includes major festivals and large marquee clubs. He calls having both his solo gig and Ween going at the same time “a blessing” and that songs he’s “played a million times feel like they’re brand new again”—but his real interest lies in the future, in what happens next. He’s proud of The Deaner Album, but it’s much more of a beginning than a culmination for him.

“I can’t wait to get past it, to be honest with you,” Melchiondo says, speaking more about the album cycle than the album itself. “I feel accomplished, but nothing compares to what has come since I finished it. I feel like that record is already yesterday’s news to me—not in a bad way—it’s just funny to me. I’m doing this interview and promoting something when I have a hundred new songs. But that’s my nature. Whatever I started with that record, I’m starting to fully realize now.

“I’m constantly in motion, constantly working on the next thing,” he continues. “I could probably put out my new record right now.” Alas, that’s not how releases work nowadays, as record companies continue to stretch album cycles to maximize sales. Although he notes the merits of the social media age—where artists can write, record and share a track in a single day— Melchiondo also recognizes that giving fans space between releases is helpful, too.

“It’s like when you go to dinner and the food comes out too quickly,” he says, showing a penchant for metaphor. “Sometimes it can be a drag— if you’re out with your wife and you set aside two hours for dinner. That’s like the way that a record company doesn’t want a record every three months. Elvis Costello used to do that, and I loved it—there was always a new Elvis record, and he toured two or three times a year when he was really cooking—but there’s benefit to that system and there’s disadvantages.”

The Costello reference also reflects another facet o Melchiondo’s thought process: While he’s consistently and decidedly looking forward, he has far too much history and experience to not speak of the past at times. And while one of his great passions is playing live music, he noticeably mourns the loss of the album as an art form.

“Nobody buys albums. For me, that’s tragic,” he says. “In this day and age, making records is this byproduct, something you do so you can go tour. I felt it on La Cucaracha [Ween’s 2007 album]. I was so disappointed—the way it was so meaningless as an album. We put a lot of work into our albums. We wanted to make something that you sat down with—held in your hand, looked at while you listened to it. We wanted you to listen to the sequence of the songs. The first day review copies went out, it was posted online, stolen, shared. That was just a bummer.”

After three decades in the business—during an especially volatile time for that business, for that matter—Melchiondo and Ween have seen it all. “Thank God Ween has been around for so long that we’ve been through five different changes in the music,” Melchiondo says, detailing their trek from radio to music videos and MTV, and up to the current coupling of touring and online streaming. He doesn’t lament the changes, but he does feel that younger bands might be getting short-changed when starting out.

“I don’t think an up-and-coming band will ever have the opportunities to develop like Ween did, you know?” Melchiondo says. “By the time we got signed to make our first record, GodWeenSatan, we’d already had seven years under our belt. We were way into our career. I think that’s really important, to go through those stages, and I don’t see that as much anymore. Not necessarily suffering though dues-paying, but…” He pauses, then gives in, laughing, “Yeah, suffering through dues-paying. That’s how you get experience, and that’s how you get better.”

Throughout all their suffering and dues-paying— and successes, of course—Ween has never been your average band, and surprising their fans—along with themselves— is part of what has kept them alive and kicking for all these years. And even though The Deaner Album is Melchiondo’s first solo record, the eclectic eccentricities hold true.

“That’s what people expect and want from us, Ween and Dean Ween Group,” Melchiondo says. “I think Ween fans would have been really bummed if we ever repeated ourselves, but we never did. And it wasn’t really intentional—it’s just growth.”