David Crosby: Crafting _Croz_

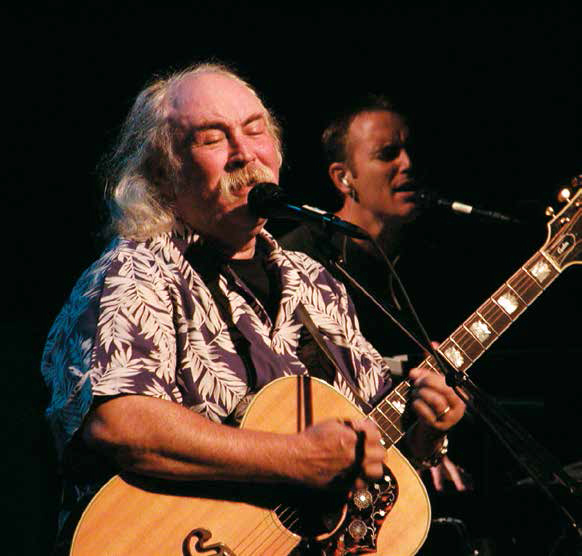

Photo by Buzz Person

David Crosby is psyched. A week after its release, his new solo album, Croz, is one notch above Neil Young’s Live at the Cellar Door in online sales. The bruising CSNY ego battles of decades past are now more like affectionate rivalries between brothers. “After 43 years, I finally got a hit!” laughs Crosby, a two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, from his family’s cozy abode in the Santa Ynez Mountains. No one but him could be more delighted—or surprised— to see his latest foray into the fertile intersection of folk, rock and jazz scaling the Billboard charts and chilling in Amazon’s Top 10 alongside the latest drops from Bruce Springsteen and Daft Punk.

The Twittersphere is abuzz with news of Crosby’s “comeback” and these kudos are particularly welcome because Crosby, now 72, never really went away. His late-‘90s band CPR—a trio with his gifted keyboard-playing son, James Raymond, and the versatile guitarist Jeff Pevar—released four excellent albums that hardly anyone heard. In 2004, Crosby and his soul mate in harmony, Graham Nash, issued a fine double album that was criminally overlooked. Why is Crosby finally getting the props he deserves? In part, it’s because Croz breaks in bold new directions for the singer- songwriter. It embraces elements of electronica and world music that make it sound completely fresh, without surrendering the soul-searching, mysterioso quality that has always distinguished his best work, from “Guinnevere” to “Déjà Vu” to the moody excursions with members of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane on his 1971 masterpiece If I Could Only Remember My Name.

Check out the heavily syncopated opening of “What’s Broken,” with a lyric about the “molecules” of a “buzzing city” (seen from the perspective of a homeless man) that shimmers like a page from one of William Gibson’s dystopias. “Morning Falling”—a stunning freeze-frame of the remote-control killing of an Afghan family by an American drone—sounds like nothing Crosby has ever done before, with a mournful Arab-inflected melody and aching woodwinds.

By contrast, “Radio and “Find A Heart” are two of the most upbeat songs that he has ever recorded–rousing tributes to the redemptive powers of love and compassion. And “Dangerous Night” unfolds with anthemic majesty over looping keyboard figures and martial drum samples, finding consolation in a postmodern balancing act between alienation and faith. Loops, samples, postmodern doubt, drone warfare? When did the shaggy paterfamilias of unreconstructed hippiedom get so hip?

Part of the answer is that Crosby—always a more forward-looking musician than he gets credit for—ceded a considerable amount of creative control over this project to Raymond, whose compositions, keyboards and arranging prowess turned the tracks on Croz into cinematic landscapes that will haunt your dreams. Raymond—who was given up for adoption by his mother as a baby and reunited with his father only after he had established his own career—was a full-on collaborator at every stage of the process, including the recording of the album in his home studio. This 21st-century DIY approach (complete with his famous dad crashing on the couch at night) enabled the father- and-son team to hone their idiosyncratic musical vision to crystal clarity without interference from meddling major-label suits.

“James walked in the door a better musician than I will ever be,” Crosby says. “He listens to lots of stuff from a very wide range of genres, from classical to jazz to pop to world music. He has a spectacular sense of time, and the way he strings a melody across a set of chords is just astounding. We work as equals—he’s not in awe of me at all. James has no problem saying, ‘I like that, but what about doing it this way instead?’”

Much of the press coverage has naturally focused on the man who puts the C in CSNY, but James Raymond, who has also clocked in time with CSN, is just as close to the heart of the album’s creative process.

How did you start playing music?

JR: My mom had a collection of 45s from the 1950s, so I would play those all the time. But once I heard The Beatles, Stevie Wonder and Elton John, I locked onto what I wanted to do in life. I played my first gigs in a funk band when I was 16. We had a horn section and really good singers. The kids at my high school in Inland Empire were really into R&B, so I loved Earth, Wind & Fire and a band called Heatwave— all that great post-Motown music. There was a piano in the band room in high school, and I had a revelation when I sat down to play a Lionel Richie song called “Easy.” All these cheerleaders and drill- team girls came out to listen—that seemed like a good sign!

When did you first become aware of the music of Crosby, Stills and Nash?

JR: Early on. I didn’t have any of their records, but whenever there was a song on the radio that had great harmonies, it would catch my ear and I would sing along. I was six or seven the first time I heard their music—probably one of Graham’s songs that became a hit.

How did you find out that you are David’s son?

JR: My parents let me know that I had come to them in a special way when I was four or five, so I always knew that I was adopted. My parents are great, very loving people—and they were smart enough to nurture my interests in music—but I can remember feeling like, “Wow, I wonder where I came from?”

When I turned 18, my dad took me down to the bank and opened up a safe deposit box. The information in the box told me that I was Welsh and Irish, that my mother liked to act and that my father was a musician. That was all I knew at first. But I didn’t really pursue it further until I was about to get married at 30 out of respect for my parents. When I got engaged, my dad said, “Now might be a good time to start searching for your birth parents.” He set the paperwork in motion for me. Three or four months later, I got a call from a woman at the post- adoptive services for L.A. County, and she was very excited. She said, “Your birth mother is also looking for you.” She told me that if I came to the office, the records were open.

So I went down there, signed some forms and they brought out this big book with all the names in it. I saw David’s name on my birth certificate and thought, “I know that name, but it can’t be the same guy!” I didn’t freak out; I just tried to absorb it for a while. By that point, I was the musical director for a show on Nickelodeon called Roundhouse, and I was working with a lot of musicians. A friend of mine named Dan Garcia—whose work as a recording engineer on Croz is one big reason why it sounds so good—did some snooping around after I told him the name on the birth certificate was David Van Cortlandt Crosby. He said, “Yeah, that’s the guy.” I talked to my birth mother on the phone and she confirmed that it was David. They hadn’t spoken since 1962.

Then my wife Stacia and I were watching the news one night and saw that CSN had stopped their tour because David was in the hospital, near death and needed a liver transplant. I was talking to my adoptive dad about it and he said, “It would be a shame if you guys didn’t get to meet.” One of the guitar players I was working with was a good friend of Mike Finnigan’s, who was the keyboardist for Crosby, Stills and Nash and also David’s AA sponsor. I called Mike and he said, “I’m going to talk to him about it, but I’m going to wait a week, so I don’t kill him with the news.” [Laughter.] At the same time, my adoptive dad had written Crosby a letter at the hospital saying, “We raised your son, and he’s a great guy and a musician.” Later, David told me that he got a lot of letters like that, most of which, obviously, were false. But he said the letter from my dad rang true to him, so he kept it.

When David was out of the woods medically, he called me. I was in the shower and Stacia came in and said, “David Crosby’s on the phone.” Her eyes were as big as saucers. David and I had a very awkward conversation, but we made plans to meet at the hospital. The day we met happened to be the day that Stacia was scheduled to go into labor to have our daughter Grace. So after we had a three-hour talk, I told David, “By the way, you’re going to be a grandfather tonight.”

Did you do any musical homework before meeting him?

JR: Yeah. I did a roots trip and bought CSN’s records and David’s album If I Could Only Remember My Name. I definitely felt a thread between my harmonic sense and his. I was particularly drawn to “Déjà Vu,” “Orleans,” “I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here,” “Page 43” and “Where Will I Be?” There was some DNA thing in there that really grabbed me. When I met David and told him that I was a musician, I could see that he was concerned that I wouldn’t be good. [Laughter.] But even on that first day, we made a huge connection over Steely Dan and Michael McDonald, who was one of my heroes. Not long after that, I went to a baby shower for David’s son Django. That day, I met Michael McDonald, Jackson Browne, Graham and my sister Donovan. It was a wild day!

What was the first song that you guys ever worked on together?

JR: “Morrison,” which was on the first CPR album. Soon after we met, David gave me a set of lyrics and said, “These are kind of weird—they’re kind of about Jim Morrison and kind of not. See if you can do anything with them.” I was very nervous about fucking it up, but I’d worked a lot like that for Roundhouse, setting lyrics. While writing “Morrison,” I listened to a lot of Joni Mitchell because I felt like if I channeled Joni, I could come up with something that David would like. I remember us sitting in my driveway and listening to the cassette in my truck. He said, “Play it again.” Then he listened to it four more times and said, “We’re definitely going to do something with this.” That’s when he got the idea of putting CPR together. We got to play the Montreux Jazz Festival, with George Benson and Phil Collins on the bill, which was certainly a high point.

What was the genesis of the Croz project?

JR: It started with “Radio.” David felt like it was time for him to do another solo project, and as we started working on that tune together, he said, “I want you to produce this. We need to write a lot of stuff together.” Not long after that, we were out on tour with CSN, and I wrote “The Clearing” on the tour bus on one of those long overnight rides. Around the same time, we met Marcus Eaton, this fantastic guitar player in Boise. David told me, “You’ve got to come up to my room and hear this kid play.” We agreed it would be cool to bring him in because he had so much energy. He ended up playing on the whole record.

The record has an extremely distinctive and contemporary sound. It’s not like CSN—and not even much like CPR—and yet, it somehow still manages to sound like a classic David Crosby record. When you hear that harmony spread at the beginning of “What’s Broken,” you know that you couldn’t be listening to anyone else.

JR: When David and I started talking about the direction of the record, he told me, “I want it to be really new. I want to do things I’ve never done before.” So that gave me license to reach for things that were outside of his normal comfort zone. He’s not too keen on drum machines and synthesizers, so if I wanted to bring those elements in, I had to make them sound organic. That’s what we were striving for—to create sound- scapes that are very modern and fresh, but don’t sound synthetic.

The vocal arrangements on the album are really David’s and his vision, and the vocals are almost exclusively Marcus and David together. “If She Called” was just two takes—one pass of David playing the guitar part, and another of him singing it. The whole track was done in two hours. It’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard, and it’s such an emotional performance. There was a lot of that: David going in a vocal booth and getting into a zone, and then him coming out and seeing us with our jaws on the floor.

I feel like David is one of the most famous musicians in America and also one of the most underappreciated. He gets typecast as that guy from Woodstock, but his solo work has been consistently deep and experimental—pushing boundaries.

JR: Certainly the harmonic complexity of his writing is so subtle that it doesn’t grab people by the collar, but is revealed upon further listening. The way he turns a phrase, the way he uses tunings—no one else sounds like David. When you listen to him sing background vocals on other artists’ work, he’s so good that he’s almost invisible. Often, it’s hard to pick out what he’s singing because he’s always got the really hard, internal harmony. That’s a good metaphor for his music: David’s songs are internal. There’s such beauty in the detail.