Cult Science: Chris Robinson Brotherhood on Their New Beginnings

This cover story excerpt originally appears in our December issue. To read further, as well as features on White Denim, Jim James, Dawes and more, subscribe here.

Chris Robinson is standing behind a recording console, wearing socks without shoes and dancing in place as an engineer plays back one of his newest songs. It’s late afternoon and the long-haired 49-year-old singer is deep into the recording of Anyway You Love, We Know How You Feel, his fourth album with the Chris Robinson Brotherhood, and the first he’s recorded in the shadow of his adopted community and spiritual sanctuary just outside San Francisco. For most of the month, his Brotherhood—guitarist Neal Casal, keyboardist Adam MacDougall and drummer Tony Leone—have been camped out at a spacious, hillside 1960s home that’s been converted into a Big Pink-like studio that members of the CRB affectionately refer to as their “arts laboratory.”

Robinson moved to Marin, Calif., in July 2015 with his wife and young daughter, and quickly identified the perfect recording space. Located in the shadow of Stinson Beach, an address now tied to the P.O. box number where Deadheads shipped their carefully decorated envelopes for last year’s Fare Thee Well shows, the studio is a true product of its surroundings—built from recycled materials salvaged from the Bay Area. Since opening its doors three years ago, the “laboratory” has welcomed a new generation of woolly indie-rockers with wide ears and kaleidoscopic tastes like My Morning Jacket, Band of Horses, Thee Oh Sees and Real Estate’s Alex Bleeker. The members of the CRB have already turned the space into a second home, sectioning off a vocal booth area with tie-dyed tapestries. A few of the band members are even staying onsite throughout the sessions, though Casal has opted to crash with his friend and Hard Working Americans bandmate Dave Schools.

“We’ve had the opportunity to make records in more conventional studio settings, and we poured all of our energies into that at the time, both what we were saying with our compositions and with our performances,” Robinson explains a few months after Anyway You Love, We Know How You Feel‘s July release. “But when an opportunity like this came to seclude ourselves away on the side of the mountain and get the cauldron stirring, we took it. It is a cult science in a way— you get a group of people who are all attempting to be in the same vibrational reality together, and you focus and you make things happen and they appear. In our case, those things are our songs. You want the compositions to be alive and you want the performances to be dynamic and you want the sounds to be unique.”

Since shifting his attention from his classic, bluesy rockand-roll band The Black Crowes, Robinson has honed in on a cosmic blend of lyrical Americana and psychedelicrock that has made his quintet a favorite on the jamband and festival circuits. They’ve toured with Tedeschi Trucks Band and regularly collaborate with Phil Lesh, both on the road and at Terrapin Crossroads. Anyway You Love, We Know How You Feel expands their sonic palette, adding additional elements of funk, soul, country and even groovy synth textures. A true indie effort, Anyway You Love, We Know How You Feel was written and produced by the band and released, like their other records, on Robinson’s Silver Arrow label.

“With the entire situation we find ourselves in, we’re really only responsible for the creative output—for our vibes and decisions, how we do things,” Robinson adds, stroking the long, unkempt, slightly gray beard he’s harvested for over a decade. “We’re the hunter-gatherers of the music business and, just like the hunter-gatherers of culture or society, we have to live on what our environment gives us. You have to exploit that fully and, by exploiting, I mean survival. So if we find ourselves with the opportunity to make a record like this, then, of course, we almost have to let every single thing go, give ourselves completely to the muse and see what’s on the other side when we come out of it.”

After playing back the dark, brooding instrumental “Give Us Back Our Eleven Days,” which is based off a soundcheck jam, Robinson moves from the studio’s lower-level recording console to an upstairs living-room space and sips on some tea. He settles into one of the room’s comfy sofas, glancing over at the weed paraphernalia spread out on a table and his impressive and eclectic record collection; a George Clinton LP currently sits at the top of the stacks. Even in CRB’s leaner early days, their late-night listening sessions helped the young band foster their musical shorthand on the road.

“A real musician loves all sorts of music—they love rock-and-roll, they love jazz, bluegrass, soul and R&B, anything,” he says. “At the end of the day, it’s a bond or a connection between people who understand the madness of it all. It’s given us great fulfillment, great joy, great adventure. It’s also been a way to deal with all the other stuff— the great confusion, the great pain and the great losses. We’re very lucky to allow the muse to overtake us in that way.”

Casal, who has served as one of Robinson’s co-pilots since the Brotherhood formed in 2011, is quick to note the important role the house served in shaping the sessions. CRB entered the studio with only three complete songs and, by the time they wrapped things up three weeks later, they had enough strong material for both Anyway You Love, We Know How You Feel and a companion EP, If You Lived Here, You Would Be Home By Now, which was released in November. Oftentimes, Robinson would work on lyrics outside by a tree while his bandmates would bat around ideas on the other side of the wall. Their telepathic connection recalls the night Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter conceived “Terrapin Station,” simultaneously in different rooms, during an electrical storm.

“When we all got into the living room of the house and Chris opened his overflowing notebook of ideas—and we all opened our instrument cases—a fair amount of magic went down,” says Casal, who has a salt-and-pepper beard of his own that reinforces the group’s fraternal spirit. “I don’t use that word lightly; ‘magic’ is a word that’s oft abused these days, but we stirred up some synergy there. It shocked me, I have to say.”

Anyway You Love, We Know How You Feel also marks the Brotherhood’s first lineup change. In 2015, Ollabelle’s Leone, best known for his work with Levon Helm during his final years, replaced founding drummer George Sluppick. The retooled CRB quickly returned to the road and tested out their chemistry. Then, shortly before they started recording, original bassist Mark Dutton decided that he no longer wanted to tour— though they didn’t make an announcement at the time— and he sat out the sessions. Bassist Ted Pecchio, whose credits include work with Col. Bruce Hampton, Susan Tedeschi and Doyle Bramhall II, subbed in the studio before the band settled on a new, permanent member to drive the low end, Jeff Hill.

The record has a different energy for CRB, jumping from the Beggars Banquet vibes of “Forever as the Moon” to the George Clinton nod “Narcissus Soaking Wet” and The Band salute “California Hymn.” And the album’s title reflects a group of brothers who are carrying the hippie-torch of the classic Bay Area acts, yet are still in touch with America’s current cultural concerns and their own search for an overall sense of sonic authenticity. Robinson, who still proudly touts that he considered a career as a writer before jumping into music as a teenager, ties the album together with his rich lyrics and timeless voice.

“On a lot of levels, you’re telling a sonic story, you’re telling a rhythmic story,” he says. “You have highs and lows and dramatic things, pretty things and ugly things, but it all has to coalesce to one thing. It’s about being open and intuitive enough to show yourself. It’s like being able to turn off a light and seeing the phosphorescent glow that something has left behind.”

CRB’s roots stretch back nearly a decade to when MacDougall joined The Black Crowes in 2007. “Adam and I are really the ones who ran this whole thing up the flagpole,” Robinson says of CRB’s formation, which started with the desire to write songs while The Black Crowes were on tour. “On days off, I’d sit around trying to teach myself some more guitar and writing. Adam brings his practice keyboard over and now we’re practicing and writing together. And then, at least for me, I can formulate some sort of overall vision of what it is supposed to look like and smell like and taste like and be like.”

It had been two years since The Black Crowes reunited, following an extended break, during which Robinson, a lifelong Deadhead, moved deeper than ever into the modern jamband world through tours with Phil & Friends and a close association with Warren Haynes. While the Crowes were long-heralded as poster boys for modern hippie culture, and often improvised in the concert, the reunited group felt looser and freer than ever. Their 2008 comeback, Warpaint, leaned into their rootsy, psychedelic side with the addition of Luther Dickinson, and its follow-up, the 2009 double-album opus Before the Frost…Until the Freeze was even recorded at Levon Helm’s Barn.

During their ‘90s heyday, The Black Crowes had the unique ability to blend the hard, blues-rock spirit of The Rolling Stones and the Faces with more mind-expanding textures, and Robinson’s interests continued to drift toward a decidedly retro mix of Americana, soul, R&B and groove-rock. With another Crowes break in plain sight and his brother and band cofounder Rich more interested in sticking with their classic sound, Robinson started a new musical family of his own.

“I knew The Black Crowes weren’t going on for those years after 2010, or it wasn’t going to go on much longer than that,” Robinson admits of their eventual 2011-2012 hiatus. “For me, it wasn’t just about: ‘I have nothing else to do.’ This was about my essence. I’m a songwriter first and foremost and all this other stuff is just because somebody has to do it, in a weird way.”

MacDougall first bonded with Robinson at one of Jonathan Wilson’s fabled Los Angeles jam sessions, which led to an invitation to join the Crowes. A product of New York’s Roosevelt Island, MacDougall says that his friends were part of the reason that there were rumors that “a whole society of people were living under the island” in the 1980s. He is a calming presence and wealth of knowledge on a range of subjects—from his native city’s complex subway system to the jazz records his parents exposed him to at an early age. “With The Black Crowes, it was cool, but there was definitely a vibe between the back lounge of the bus and the front lounge—the little barriers between people that had been with each other 20-something years,” he says of his time in the band. “There’s just a lot of baggage that comes with that. [With CRB], it’s nice to see people wandering around the tour bus and being able to be anywhere. It’s not like you’re in the wrong section.”

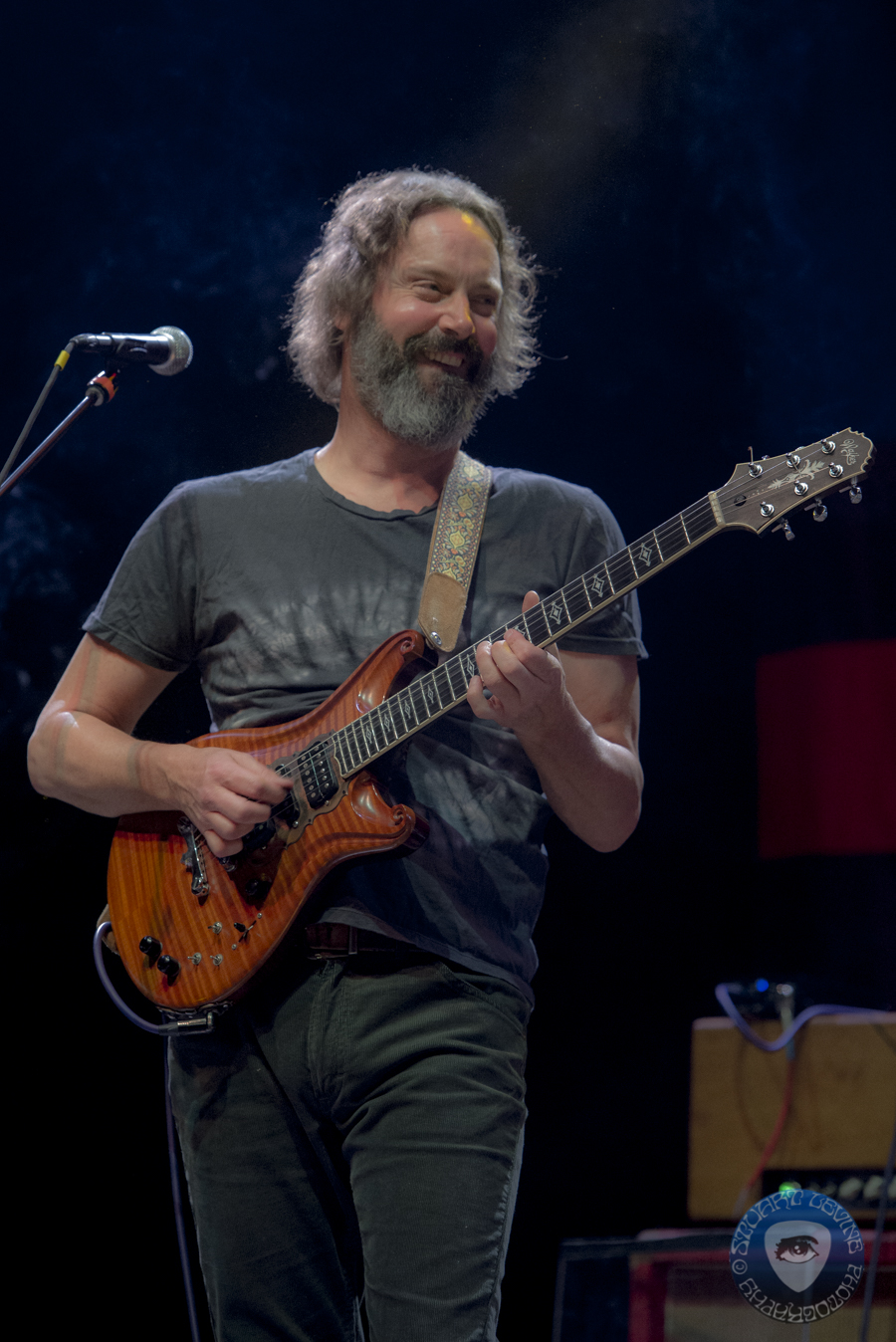

Wilson was initially supposed to be a member of CRB, but left before the project took flight, and Robinson recruited Casal as his guitar foil. They’d run in each other’s circles for years, and even spent time on the road together when Casal’s former band Beachwood Sparks opened for the Crowes. In addition to his own journeyman solo work, Casal is an accomplished photographer and was a key member of Ryan Adams’ most collaborative ensemble, The Cardinals. CRB marks the start of a busy second act that includes parallel projects like the jamband supergroup Hard Working Americans and the instrumental ensemble Circles Around the Sun, which grew out of the set-break music he wrote for last year’s Fare Thee Well concerts.

“Neal’s done it all: He’s written great songs, he’s made great records, he’s toured by himself, he’s been in a band,” Robinson says. “That shows me someone who sees their life as their work. The songs we write, the gigs we do, the songs we sing—that’s all part of the life and very little of that has to do with fame or money or stuff like that. Hopefully, it’s about existing on a deeper level. It wasn’t very hard for me [to start a new band so deep into my career]. The cool thing is that, for as many records as we’ve all made, we all feel like this is the first record and it still feels new to all of us.”

Like Robinson, as a young musician, Casal used the Grateful Dead as a portal to discover numerous forms of American music. He saw both the Dead and Jerry Garcia Band while growing up in New Jersey and also developed a deep appreciation for other touchstones that Robinson cites, like funk, country and The Rolling Stones. After playing indie-rock bars and DIY clubs for years, Casal is somewhat amused by the current hipster underground’s newfound claim to the Dead. He re-entered the Dead’s orbit when Adams “was fairly obsessed with the Grateful Dead and exploring those avenues on a vibe level during the Cold Roses era, extending into Easy Tiger, and that got me into it a little more deeply.” In 2006, he played with Lesh for the first time when the bassist sat in with The Cardinals at the Hollywood Bowl. (Casal describes the collaboration as being in the right place with his guitar on at the right time.)

CRB rounded out their initial lineup with Dutton and Sluppick, the latter of whom had clocked in time with Albert King, Robert Walter’s 20th Congress, Sha Na Na and JJ Grey & Mofro. From the outset, Robinson envisioned the group as an entirely new band with a new catalog and fresh skull-and-roses identity of their own.

“Honestly, if the idea for the band was to be a satellite of The Black Crowes, then I wouldn’t have been interested, personally,” Casal says. “Don’t get me wrong, I’ve been a Crowes fan since day one, but I’m not personally interested in playing heavier rock music like that. I’m more into their acoustic side or their country side, but I’m not a rock-star guitar player. To pursue a more Grateful Dead, folk and jazz-inspired thing was much more my taste, especially at this time in my life.” He pauses and rephrases his thoughts. “It’s not like we can really play jazz, but there’s a mindset, an openness within the music. The guitars don’t necessarily fill up all the spaces and there’s room for all of Adam’s keyboard work, which opens up horizons of possibilities. It’s just a different kind of music that’s coming from a different place.”

To read the rest of the cover story, subscribe to Relix.