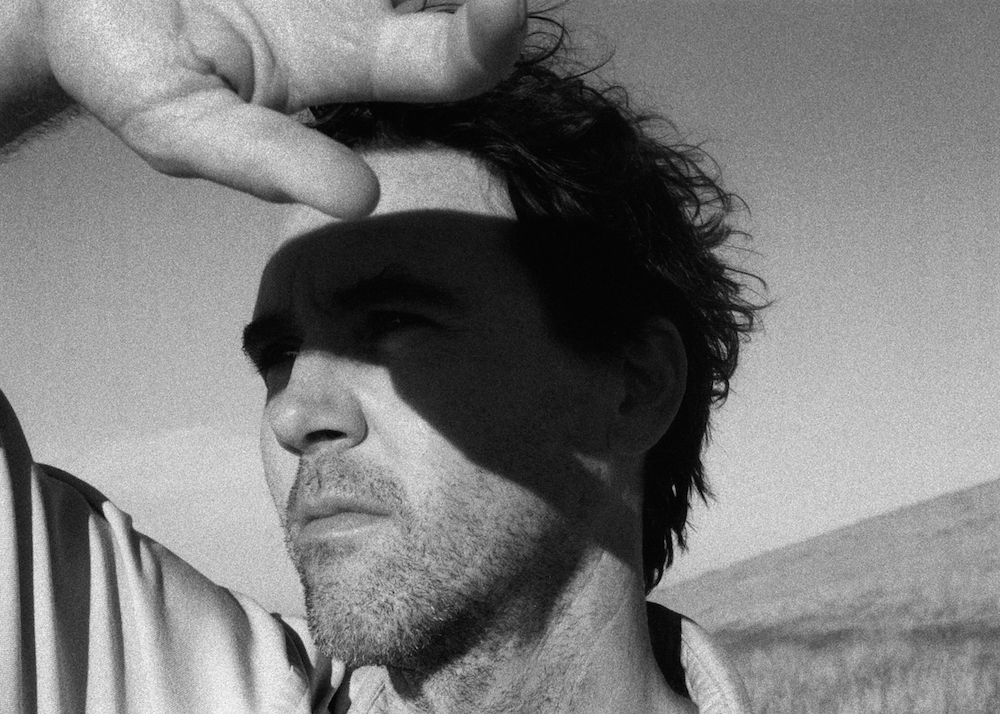

Cass McCombs: Mangy Love Songs

“There’s so much research to be done on people’s actual work that, sometimes, I’m distracted by their biography,” Cass McCombs tells me, as we take our seats in the bar of a private club in downtown San Francisco. I can’t help but wonder if he means that as an anecdote or more of a warning: “Don’t write my bio. Anyone can find that out on the Internet. Write about what’s interesting instead.” That was already my intent, so it’s off to a good start.

“There’s so much research to be done on people’s actual work that, sometimes, I’m distracted by their biography,” Cass McCombs tells me, as we take our seats in the bar of a private club in downtown San Francisco. I can’t help but wonder if he means that as an anecdote or more of a warning: “Don’t write my bio. Anyone can find that out on the Internet. Write about what’s interesting instead.” That was already my intent, so it’s off to a good start.

And, yeah, look, if you want to know Cass McCombs’ timeline and statistical data, then I suggest a quick glance at his Wikipedia page: “Born Nov. 13, 1977 in Concord, Calif.; released his first EP in 2002; toured with Arcade Fire, Band of Horses, War on Drugs; genres: rock, folk, psychedelic, punk, alt-country.” But for those already familiar with him as an artist, reading the bio can make you feel like you’re Capt. Willard reading Col. Kurtz’s dossier on his way up river. If musicians were an army, then Cass would be plenty well decorated, but for the social media generation, where history no longer matters, neither does that.

So, then, this is not a Cass McCombs bio. We don’t have time for that distraction. This is a conversation with the artist, conducted over one too many glasses of wine, from the cozy confines of an elite private urban country club where tech secrets are traded and power deals are made with a handshake and, perhaps, another round. Little wonder, then, that we talk less about the album—or, for that matter, his music specifically—and more about art in the abstract, set against a backdrop of “life, the universe, everything.”

The club is called The Battery and, at first brush, it might seem like one of those privileged places that a “people’s artist,” such as Cass, could have their share of hesitations about. The Battery certainly tailors to a very select—and, for the most part, admirable—crowd. It counts, as card-carrying members, no shortage of techies, entertainment lawyers, liberal-leaning politicians, investment capitalists, trust-fund grown-ups and Wild West entrepreneurs. The club does not represent one ideology, nor does it push any agenda. Instead, it actively supports, encourages and fosters a sense of community. That is, the community within and the community without. Its members are generally aware that they are part of an elite, and they are glad to mix among such like-minded company; but they also are generally aware that with their money and influence comes responsibility to the greater good. They are asked, here, to become leaders, examples, role models—and, above all, to be cognizant, aware and engaged.

It’s what we, as a culture, ask of our artists. Little wonder then that The Battery opens its doors (and arms) to artists of all types, aware that it is the creatives—the Cass McCombs of the world—who first give voice and context to communities and, within those communities, movements, mobilization and, ultimately, action networks. All of which could form fl w charts that would somehow look familiar to Cass, even if they were found crumpled up in his waste bin.

Look: Cass McCombs is complicated. He’s not a contradiction; he’s just complicated. He gives the impression that he’s never been fully pleased by anything ever written about him, yet he agreed to do the interview, although his management said that this might be the last interview he gives for a while.

Listen: Cass will likely find some amount of disgust in any analysis either because he doesn’t identify with the depiction, or because he does but doesn’t want to admit it, almost like hearing yourself talk on tape for the first time. But in these dark and uncertain times, we need him more than ever. He’s the type of artist that conscientious citizens could really lean on, looking for clues to something, but what exactly, who’s to say: We don’t know what, and Cass probably doesn’t either. He’s looking with us. It’s his art, like all art, that whispers the clues. Maybe what we’re looking for is permission. Permission from an artist (who claims no other authority) to be furious with the government, furious with politicians and reality TV stars alike…Permission to engage in the oncoming era of political unrest and permission to disengage from it entirely. As he sings on the opening song to his new album, Mangy Love, “And eulogies poured from the stage/ but nothing changed.” (The double-take moment comes a couple verses later, when he sings: “Sent a letter to my congressman/ the Ku Klux Klan/ from my pierced hands/ bum bum bum/ They sent me back an Apple phone/ a fine-hair comb/ and a bell tolled/ bum bum bum.”)

But Cass is right in that it’s hard to cast him as a typical artist, and doing so would be a great disservice to his work. An easy example would be to point to his website—the obvious place for commerce and accessibility. Most artists would want their online portal to have content relating to their latest products, complete with purchase links, an online store, photos, favorable press clips and a current bio. Cass’s website has none of that. Instead, it offers a free download of an original font (“Die Sect”) that he and his friends came up with, for fun, by dismantling and altering the peace sign. Instead of an “About” section, there’s a seemingly outdated “This Site’s History” page. There are lyrics, but none from Mangy Love. There’s a “Video” section, featuring just one brilliant video, for “Laughter Is the Best Medicine”—certainly one of the highlights from the new album. But in order to view the other new videos, you have to search for them on Vimeo.

“Laughter Is the Best Medicine,” by itself, would likely appear on a Pandora station for Super Furry Animals. The video is barely abstract, certainly confusing, but undeniably compelling, much like the song and the artist behind it. In fact, it’s eye candy for ear candy. Of course, Cass himself will likely wince when he reads that sentence.

Dig a little bit deeper, though, and perhaps the video is meant as a metaphor for the song’s lyrical content. It pairs lazy landscape scenes with politically charged images, but one is never quite sure of the intent or agenda. There’s a protest of some sort, the remnants of a Bernie Sanders rally, a parody of the HRC campaign with the hashtag #freechelseamanning and—perhaps most important—a cat licking itself in its forbidden parts, bookending the whole thing. Cass sings, “Sugar and spice and everything weird.” It seems like the message, if there is one, is that the revolution— and revolution— can go be and do whatever, off in th distance, and as the images flash across our television sets and mobile devices, we’ll make jokes and keep each other laughing at cat porn while Rome goes down in flame . And it’s all on equal ground. I like that interpretation. But is that what’s really going on here? Again, who’s to say?

Cass should know, so I text him. I did this just now, in real time, while writing about it, and relayed my interpretation, asking almost apologetically if I missed the mark. “That’s hilarious,” he writes back, almost immediately. “Hadn’t thought about that, but I dig it.” Naturally, he doesn’t offer a alternative explanation. I don’t follow up.

Instead, I recall something he said during our meeting at The Battery: “I think I believe in a world that defies, and is beyond, description. So when I’m writing, I’m asking myself: ‘What’s a song I haven’t written yet?’ I’ve written about this, I’ve written about that, but it’s a pretty big universe, so what haven’t I talked about yet? Maybe even something that’s slightly contradictory to something else I’ve firmly held on to as a belief—let’s challenge that. Let’s fuck with my own beliefs.”

I suppose that’s how a song like “Rancid Girl” makes it from the notepad to the final tracklist on the album. Featuring an intro by Phish’s Mike Gordon (on guitar and vocals—not bass) the song is an unusual sort-of nightmare love song to an unworthy heroine from a man who expects to kill himself before long. (“You’re a rancid girl/ in a rancid world/ but I don’t mind.”)

I wonder how I can relate to such an undeniably catchy song. I am reminded, then, of something Cass said while we were waiting on the waitress. After conceding that many of his songs are written from the perspective of other people, real or imagined, and from all different walks of life, he pauses to think for a moment, then postulates, “Naturally, they will appear on the surface as being contradictory, but these are just surface things like politics, gender, race—things like that. I view those as surface things. There’s something more universal that we all have in common that’s more hidden.”

If Cass can reveal the hidden commonalities, under the surface of the quagmire that we all wade in, then he will be as important as I think he is during this dangerously dividing time in our nation’s history. But Cass probably doesn’t want to feel the weight of that responsibility, which might be why some of his work is just outsider and unusual for the sake of being outsider and unusual. It doesn’t always have to mean something to matter. (“It can be funny and devastating at the same time,” he says). Plus, there’s something undeniably charming about the fact that a couple years ago, Cass wrote a song directly inspired by a quirky jingle that Mike Gordon wrote—almost as a joke—about his mom (“Minkin”) for Phish’s 1986 hand-dubbed cassette, The White Tape.

He first met Mike in 2012 when they both played at Bob Weir’s “Move Me Brightly” Jerry Garcia tribute and he’s appeared on every one of Cass’ subsequent albums: 2013’s Big Wheel and Others, the 2015 compilation A Folk Set Apart and Mangy Love. Mangy Love also features an incredible list of contributions from sonic innovators and improvisers, including Joe Russo, Blake Mills, Farmer Dave Scher and Stuart Bogie.

Yes, that’s right. Cass is influenced by Phish and the Grateful Dead. “I saw Jerry play many times,” he says. “I was there, front row. I felt it in a heavy, heavy way. We don’t have to talk about it.”

An hour later, when trying to make a point about something else entirely, I let slip my own affection for Phish “They’re great,” he interjects, immediately, eyes lighting up. “I can talk about Phish. I don’t really want to, but I can.” (He started seeing them live in 1993 and says he’s “been picking away at their tunes” ever since.)

I understand Cass’s hesitancy to talk about two distinct bands that have a massive audience and, hence, a ton of musicians trying to ride their coattails. Cass isn’t trying to cash in on that wave—the thought of it alone is repelling. Also, there’s a formidable stigma around both their respective scenes that seems to affect the other artists that dabble professionally in their worlds. I tell him this.

“I don’t believe in any kind of scene,” he counters. “It’s just people, one on one. If you’re a cool person, it’s just you. It doesn’t mean all your friends can come too. Growing up in the ‘90s, we had MTV, and I hated MTV. We had so much venom toward the mainstream. That’s partly why we went off to the Dead, who were still active. I was into Nirvana, and I remember when Kurt Cobain wore that ‘Kill the Grateful Dead’ shirt. I remember that. But growing up in that time, everyone I knew was completely aware of how the media and businesses wanted to manipulate us—people between the ages of 14 and 17. They wanted to get us to believe in ‘alternative music,’ and we’re like, ‘Ain’t going to happen, guys. We’re ahead of you on this, and we’re way too savvy.’”

For all his entanglement with bands that would be considered “indie”—My Morning Jacket, Modest Mouse, The Shins—Cass has recently been hand-picked by the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh to perform with him in several all-star lineups, and Lesh’s ex-bandmate Weir even covered one of his songs (with members of The National).

“The thing about it is that you don’t want to hide behind riff ,” he says, of playing with members of the Dead. “Improvisation is easy if you can just fall back on those well-rehearsed idioms that you’ve done over a million times, so it’s not really improvising— you’re connecting little Lincoln Logs or something. But true improvisation is just listening, really. It’s not about you. It’s about listening to what other people are doing and contributing to what they’re doing.”

We riff on improvisation, and I make the comparison to the conversation itself, as neither of us knew quite where our afternoon at The Battery would lead us, topic-wise, and we just kind of bounced around based on what the other was saying. No agenda. The journey is the destination, and at least we’re enjoying the ride.

“There’s another element that people never talk about, which is what I call giving up the ghost,” he says. “When you feel that surge, the group has its own mind and its own crazy insane cracked logic that it’s moving with. That’s why I love punk—because punk did that. It’s coming from a very visceral place and it’s not egotistical. The group funnels their energy into one person—it could be the bass player, it could be the drummer, it could be the fiddle player, singer, whatever. Sometimes, it’s like a cannon and shoots energy into individuals like that. It’s completely random and it’s not planned. I love that. It’s frightening.”

Cass’ manager tells me that he splits his time between the East and West Coasts and that, despite growing up in the Bay Area, he identifies as a New York artist. I respect that, but I’m not so sure I buy it entirely. A day or two after our wine talk, Cass starts shooting me a series of text messages. He’s been actively pondering some of the topics we touched on. (Example: “I’ve been thinking about what I’ve learned from playing with Lesh and Weir, and I think it’s going to take some time to understand what they actually taught me, ha ha.”)

Cass’ manager tells me that he splits his time between the East and West Coasts and that, despite growing up in the Bay Area, he identifies as a New York artist. I respect that, but I’m not so sure I buy it entirely. A day or two after our wine talk, Cass starts shooting me a series of text messages. He’s been actively pondering some of the topics we touched on. (Example: “I’ve been thinking about what I’ve learned from playing with Lesh and Weir, and I think it’s going to take some time to understand what they actually taught me, ha ha.”)

Pretty soon, the texts start to get heavy, as we toss the ball back and forth about whether or not artists have a social responsibility, whether or not activism actually accomplishes anything (“what one person calls cynicism another calls activism”) and the notion of psychedelic consciousness.

“Music is a cell, it is of the body, so naturally it brings people together,” he writes. “I know I talk a lot of trash, but all my friends are talented trash talkers and it’s all in humor and love. My own music is how I get out my confusion. Some of these ideas are ephemeral and many people take issue with the word psychedelic, which I also understand. But perhaps it’s in the place of a feeling that is indescribable.”

Before I can respond, he sends two rapid fire texts: “I got to think about this a little more!” Followed by: “Point is, I don’t know, just trying to figure it out like everyone else. Probably nothing to figure out.”

I push him on activism, asking if it’s vanity (“I know people who cannot vote because they’ve been convicted of a felony; they certainly don’t think that activism is vanity” he shoots back) and/or the age-old debate as to whether or not artists have a duty to be sociopolitical weather vanes, mouthpieces, etc., versus just making really cool sounds that we can dance to and escape from all that noise for a bit. It’s a two-sided coin.

But then he lets it drop that he witnessed a horrendous hit-and-run accident earlier that morning, and apologizes by saying he’s “feeling very goth.”

And that’s when he reveals something about his upbringing that gives genuine context to Cass McCombs, the artist. After remarking that Judy Collins and Liam Clancy were helping him feel normal again, after witnessing such unexpected violence, he sends me the following: “Impossible to forget how heavily the Vietnam War affected all of our favorite music from the ‘60s.” This leads into a back-and-forth about our mutual love and early discovery of the Woodstock film and soundtrack, to which he adds: “Also, growing up in the Bay, the ‘60s antiwar movement was still very potent. Still is actually. And we’re still at war. Only difference is we are living in Vichy France now where very few will speak up.” A minute of silence before my iPhone vibrates again. Another text: “Also, my grandmother knew the Black Panthers and blah blah blah.”

It sounds like a potential future song lyrics, especially the “blah blah blah” bit. After all, Mangy Love kicks off with a song called “Bum Bum Bum.” Perhaps the elusive meanings embedded throughout Mangy Love— and the wisdom wrought from them—can be found at the end of the video for “Medusa’s Outhouse.” The NSFW video is an incredible example of pairing a song’s general meaning with a parallel storyline that’s not a literal reenactment. In this case, a song that might be about the redemptive qualities of music, and its ability to o˜ er us an escape hatch from the everyday, is set to outtakes from a porn shoot and a staged, behind-the-scenes look at those who set out to find the American dream, only to discover the Hollywood nightmare. “I thought I was going to find something out about myself,” says one of the porn stars, when asked what first brought her to LA. Did she find it? “I don’t know,” she says. “I think I turned out to be a different thing.”

After immersing myself in the dreamy sounds of Mangy Love for a few weeks, looking for my own answers, I think I know exactly what she means.