Brian Wilson’s Enduring Sunshine

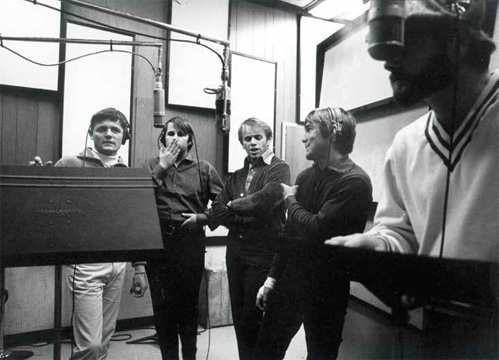

In the lobby of Hollywood’s iconic Capitol Records building, among the framed black-and-white pictures of the myriad renowned musicians on the label’s roster—both past and present—is a color photo of five barefoot boys on a misty Malibu, Calif., beach. There is Mike, the eldest of the quintet at 21, with his shirt unbuttoned, casually settled in the sand. There is David, 14, sitting on the edge of a longboard turned on its side. And there are three brothers: Carl, 16, hunched behind the wheel of a yellow pickup truck decked in palm fronds, and Dennis, 18, whose faraway eyes and hirsute locks are the embodiment of the Southern California surfer. Brian, 20, tall and scrubbed clean, looms slightly larger than the others, though farthest from the camera.

“I’ve moved beyond it,” says Brian Wilson. “Far beyond it.” Several floors up at Capitol, in a spacious suite outfitted with several chairs and tables, a small couch and a piano, the 72-year-old musician is talking about his latest separation from the band that he co-founded, and how he had written nearly a dozen songs for the group’s next album, a follow-up to the 2012 reunion hit, That’s Why God Made the Radio.

The decision to stop The Beach Boys’ reunion tour prematurely was reportedly made by frontman Mike Love, instead of original creative force Brian Wilson. It left the future of the group—as with previous splits—tenuous and uncertain, but didn’t dampen Wilson’s desire or ability to continue making music. Out of these ashes comes No Pier Pressure, his 11th solo studio album, featuring a slew of special guests including fun.’s Nate Ruess, She & Him’s Zooey Deschanel and M. Ward, also- excised Beach Boys Al Jardine and David Marks, and Blondie Chaplin (who was briefly a member of the band in the early 1970s). It wasn’t conceived as a solitary effort, and for all intents and purposes, it sounds, at times, more like a Beach Boys offering (minus Love) than a Wilson solo outing. Those nonpareil harmonies, paeans to summer days and Saturday nights, and young hearts racing and breaking are all present and accounted for within the 13 numbers. (A deluxe 16-song set is also available.)

“I wanted to make sure the new ones had good lyrics,” says Wilson, who created 14 of the tracks with producer Joe Thomas. It was Thomas who coordinated the 50th anniversary reunion, recorded and mixed That’s Why God Made the Radio, and co-wrote most of that record. While Thomas’ participation certainly contributed to the sonic and lyrical continuity from the predecessor, the spiritual aura that inhabited that title track—and has been a recurring influence in Wilson’s writing since the mid-1960s—is less obvious and more between the lines on the new set. Instead, love is the overarchingthemethroughoutthepost-break-upcollection.“Mostly, that’s what the record was supposed to be,” Wilson explains. “A love record.”

It was an appropriately bright and sunny day on the roof at Capitol when, in December of 2011, classic Beach Boys members Wilson, Love, Jardine, Marks and Bruce Johnston, full of goodwill and optimism, gathered to announce a new album and subsequent tour. Returning the band to the glory of their indomitable commercial peak, That’s Why God Made the Radio reached No. 3 on the charts, and the group’s U.S. and European trek turned into one of the year’s top concert grosses. Then, Love scheduled a series of fall shows with a touring version of The Beach Boys that did not include Wilson, Jardine or Marks, effectively snuffing out any further activity with the reconstituted, surviving principal members of the group. It was the latest in a series of dramatic family squabbles. Love has licensed The Beach Boys name since Carl Wilson died in the late 1990s and has continued to tour under that moniker with Johnston and a revolving group of sidemen. He agreed to put his Beach Boys on hold in 2012 for the new album and a world tour celebrating the band’s 50th anniversary, but after that run came to a close, he returned to the road with Johnston and a group of hired hands.

“Let’s face it, we had a very successful 2012 with The Beach Boys reunion and then, all of a sudden, it was gone,” says Thomas. “We’d be inhuman if we didn’t have fond thoughts about the wonderful year we had—in Brian’s case, going back to when he and his cousin Mike were singing at six years old. He’s got those fond memories, and I think those memories leak into these songs.”

Armed with the handful of tunes in line for the follow-up to That’s Why God Made the Radio, Wilson soldiered on with plans of his own, even if the destination had shifted. “When we’re in the studio and Brian is talking about parts—and there are five parts in a song—he’ll go in and say, ‘I’m going to sing Mike’s part right now,’” explains Thomas. “This is not a guy who is going to separate capitalism and the business of music from the musical thoughts going on in his head. He still hears Mike singing these parts whether Mike ends up singing them or not. There was no lament. It’s just how he hears it. It’s a very simple, honest, really pure Brian-esque way he looks at things.”

Still, despite the reunion run’s nasty end, or perhaps because of it, Wilson did have the services of his longtime mates Jardine and Marks available to him, utilizing Jardine’s vocal harmonies on four of the album’s tracks that are most reminiscent of the classic ensemble. “It’s easy for both of us,” says Jardine of the No Pier Pressure sessions. “We have a working relationship that goes back to the beginning of time. So, it’s pretty much: Walk up to the microphone and sing. I know what he wants and he knows I can deliver.”

Jardine, too, was immediately aware of the lyrical slant toward relationships on many of the new songs. “No doubt. That’s Brian all the way. He’s deeply sensitive to relationships,” he confirms. “It was nice to have some material that means something.”

Another historic relationship that continues to mean something to Wilson is the one he shares with Ocean Way Recording, home to an immeasurable number of his sessions—both solo and with the Boys. Opened in 1961 and originally known as United Western, the venerable recording studio sits at the center of Los Angeles’ Sunset Boulevard, and for Wilson and The Beach Boys, it’s been a comfortable homebase since their groundbreaking 1966 single “Good Vibrations,” as well as most of the legendary Pet Sounds. The studio has always functioned as an instrument of Wilson’s during the hundreds of hours he’s spent inside making his best music.

“It was quite interesting the way the process went,” says Wilson. “Sometimes it will be spur of the moment, like I’ll say, ‘I want to record today.’ I’ll call the musicians and say, ‘Come down really quick.’ Or sometimes I’ll take a couple of weeks to make a decision.”

Carrying a reputation as somewhat of a prodigy for his early mastery of arrangement, Wilson concedes that the chord patterns and melody come first, followed by the lyrics. “I can’t hear the music until I get into the studio,” he says.

As a collaborator, Thomas describes a method free of demos and little in the way of rehearsals. With tapes always rolling, the two sit at their respective grand pianos working out song after song, with some ending up fully realized and others fermenting as prospective ideas.

“Thank God that we’ve had record companies over the years that have believed in the projects and given us budgets to make these kinds of records because we don’t do any demos. This is all done in the studio,” says Thomas. “Brian is not a ‘practice player’ to borrow a term from sports. He’s a real ‘game-day player.’”

The often-romanticized image of a top-down drive under a faultless sky up the Pacific Coast Highway is now part of the American consciousnesses. The car culture of the 1950s and ‘60s— resulting in a bevy of music and movies narrating and projecting boundless freedom and adventure—was further enhanced by the addition of bikini-clad Bettys and their surfer beaus romping in the sea and sand. It’s also a source of inspiration Wilson has been tapping into for over five decades.

“A lot of times, when we write our lyrics, we take drives along the beach,” Thomas explains. “As a California guy, it’s right there at his disposal. You get the natural breath of fresh air, and it just kind of creeps into his songs.”

A different kind of creeping known all too well in Los Angeles comes from the inevitability of traffic—in this case, it was caused by construction on Sunset during the album’s creation. Detouring with Thomas to the parallel Hollywood Boulevard for several drives home from Ocean Way gave Wilson inescapable time to reflect on this street, where visits are a rite of passage for many. Apart from the day’s fashions, he saw that not much had changed since his youth, and chose the celebrated stretch, with its souvenir shops and sidewalks of stars in cement, as the prime backdrop for an ode to the simplicity of everlasting love on “Saturday Night.” Befitting the cross-generational perspective, Wilson cast Ruess, fresh from pop-chart success with fun., to sing lead while he provided counterpoint and harmony.

While both Wilson and Thomas describe writing the album as an organic process, they each acknowledge wanting to represent particular styles and eras of music, something that Thomas calls “pocket symphonies,” such as vintage Motown or the late-‘60s, bachelor-pad swing of Herb Alpert. There was, as well, a conscious desire to include current artists like Ruess and Capital Cities’ Sebu Simonian, some of whom came to their attention thanks to their children and grandchildren. “I was a little on the floor,” recalls Ruess on being asked to appear on the album. “I thought it was really cool that Brian was writing with me in mind.”

Ruess says that his indelible keepsake moment from the experience came while stacking harmony parts, as Wilson pushed the singer into higher ranges. “We’re in Ocean Way and I was looking through the glass while recording vocals, and I just saw Brian looking right up as soon as I was hitting these insanely high parts,” says Ruess. “Then he gave me a ‘bah-bah-bah’—these notes he would probably have written for Mike Love. That was as good as it gets.”

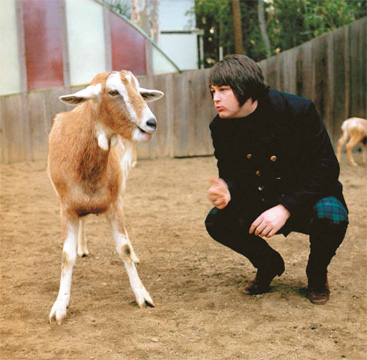

Though he’s already contemplating his next album, a rock-and- roll tribute to influences like Chuck Berry and Phil Spector, Wilson is taking to the road in support of No Pier Pressure. He made an appearance at the Fonda Theatre’s Brian Fest in March, joining the likes of Norah Jones, Brandon Flowers and others gathered to honor him. There’s also Love & Mercy, the Wilson biopic starring John Cusack that screened at SXSW before its June 5 opening. His summer schedule finds him mostly playing outdoor sheds in the States before a September trip to the United Kingdom for arena dates. He’s moving on as he always has, attributing luck, more than anything, to his success.

“He’s one of the pure artists that you’ll have the good fortune to meet during your lifetime,” says Jardine, whose son Matt serves as Wilson’s current musical director. “He has no ulterior motive, other than to make the best possible music for the best possible reasons.”

“I don’t like to throw the term ‘genius’ around, but I always thought, out of everybody, Brian Wilson was a genius of that era,” Ruess adds while appraising the golden age of The Beach Boys. “Now, meeting him in the flesh—it is so true.”

Brian Wilson, his genius and his love have endured, but certainly not without pain. He buried brothers Dennis and Carl far too early. He has succeeded in writing, producing and performing music of the forever young, but always in an industry where his competition keeps getting younger. His hair, still neatly blown back as if by a Malibu breeze, is mostly gray. The chair he sits in looks west into a postcard view of an endless summer in Southern California. When asked about the opening song from the album, the concise and exquisitely haunting “This Beautiful Day,” he answers, curiously in the past tense, with a response for perhaps more than just the question: “It was beautiful, wasn’t it?”