Being a Grateful Psychiatrist

My experience as a proud second-generation Deadhead (and the son of an original Deadhead) was inexplicably changed after my first Grateful Dead concert as a psychiatrist.

This particular show was somewhere around my twentieth Grateful Dead-related concert which is far less than the Chief of our Department at my old hospital has under his belt (and threatened me never to tell anyone else about).It was held in a hockey rink-turned-concert-floor with the regular cast of characters that one would expect to see at a concert featuring the surviving members of the Grateful Dead.There was the flabbergasted toddler in a tie-dyed shirt and a cloth diaper riding on his mother’s shoulders and trying to figure out if he should be grooving or crying hysterically.There was also the elderly man sitting a few rows away from me that I lovingly dubbed “Methuselah,” given his heroic white beard, the fact that he must have been at least eighty, and the eerie feeling that had just stepped out of Ken Burns’ documentary, The Civil War.

Examining my concert neighbors showed a variety of clinical symptoms.There was the intoxicated fellow in my row with “notable horizontal nystagmus”—a medical term suggesting the person had the googly-eyes of drunkenness.A bizarre pair of dancers showed “choreoid movements of their upper extremities”—a neurologic description of gyrating movements.A young woman who sat on the ground with a yellow winter hat pulled over her face was having the debate of a lifetime with herself.

Sometimes crude medical interventions were nearly necessary, making me grateful that I had spent some time working in the emergency room as a resident.For example, there was the middle-aged Caucasian man who slumped down three rows in front of me during the sound-check, spilling a beer on his lap.As his friends tried to prop him up against a chair to avoid any suspicion, it became clear that the man was pale, sweating profusely, and grabbing his chest.I approached a security guard and whispered to him that the EMTs should evaluate our fellow Deadhead.I wasn’t going to Narc on anyone; I just wanted to make sure this fellow who was drunk and clumsy wasn’t also having a heart attack.

My skills as a consulting psychiatrist who assists frustrated primary care docs in “dealing with difficult patients” were useful during a bathroom break.Here I was able to help another inebriated guy avoid arrest when his incessant and slurred calls for his friend, “Harry Shaugnessy” attracted the local authorities outside of the lavatory.Luckily I convinced the poor guy to “Chill out, just have fun, and enjoy the show,” and the police officers to “let me take this poor guy back to his seat.”I think this may have avoided what could have otherwise ended in multiple unnecessary intramuscular injections and four-point restraints at the nearest hospital emergency room while he sobered up.

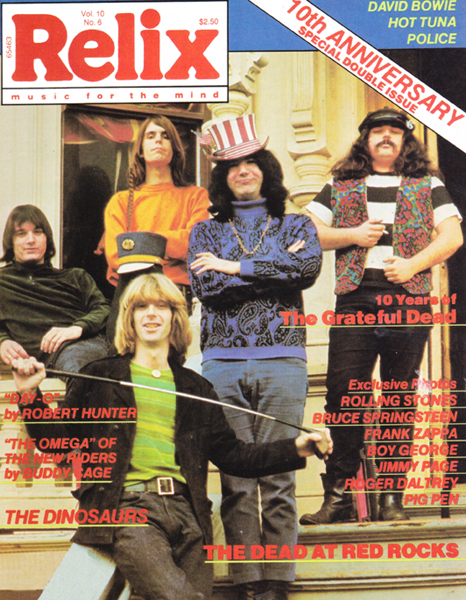

Then there was the sadness I experienced in witnessing the decline of my beloved Grateful Dead.While Jerry Garcia and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan have been gone and mourned for many years, the mortality of the surviving band members now becomes more evident with each year’s shows.Whether the tortured vocal cords that can no longer belt out the chorus to “Uncle John’s Band,” the fingers that cannot pluck the solos for “Playin’ in the Band” as fast as they used to, or the fact that the lyrics to “Cold Rain and Snow” are recalled with teleprompter, the Grateful Dead of my youth was “Gone, gone, and nothing’s gonna bring’em back.”

In spite of this, the band put on quite a show.Perhaps it was best put by an obese older fellow who approached me in a dazed fashion and said, “This is the best night of my life!I wish I hadn’t blacked out or had a diabetic seizure or something so I could remember more of it!”Unfortunately, the man disappeared into the crowd before I could assess the issue further.This moment certainly left me with a newfound appreciation of having maintained consciousness throughout the concert.

One notable highlight of the show was its encore, “Ripple,” played gently and acoustic.I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t quoted the lyrics—“If I knew the way, I would take you home”—multiple times in subsequent psychotherapy sessions with my patients.

As a doctor, I often struggle with the transition between work and home—at times I spend the entire night agonizing over the decisions I’ve made and their unavoidable consequences.These thoughts can never truly be compartmentalized, even after signing out my pager at the end of the day.Sometimes, however, I’m faced with the alternate challenges of discovering new diagnostic and treatment dilemmas long after I’ve left the hospital and with people for whom I never had a clinical relationship.Sometimes this even occurs at Grateful Dead concerts.Or better said, inevitably this occurs at Grateful Dead concerts.Perhaps I’m just glad that I didn’t run into any official patients from my clinic at the show.“What a Long Strange Trip” that would be to discuss during our next appointment.

___

Jacob L. Freedman, MD, is a board-certified psychiatrist practicing in Boston, Massachusetts, and an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Tufts University School of Medicine. He is a graduate of The College of William and Mary, The University of Massachusetts Medical School, and The Harvard Longwood Psychiatry Residency Training Program where he was Chief Resident of Inpatient Psychiatry and the recipient of the Henry G. Altman award for Excellence in Medical Education. His clinical and academic interests include psychopharmacology, integrated psychotherapy, and medical education. His non-academic interests include suburban-mountain biking and Middle Eastern cuisine.