Behind the Scene: Jason Miller

Photos: Stephanie LaFera (Kaskade’s Manager), Kaskade and Jason Miller (l-r)

“I believe that music is the great equalizer,” explains Live Nation New York President Jason Miller. “It’s the only thing on the planet that everybody has in common. I believe that if a person goes to a concert and has a great time, they can be a better human being than they were when they got there—and that’s my responsibility.”

What was the live music scene like where you grew up?

I grew up in Portland, Oregon. It’s always been a pretty great live music town. I think there’s more attention focused on Portland these days now than there was when I was growing up. But Portland always had a very vibrant music scene with local and regional artists, a longstanding blues festival, we had this thing called the Rose Parade and there was always the tournament of Roses. There was all kinds of stuff happening at the waterfront among them being music. Also the downtown core there’s this place called Pioneer Courthouse Square and there would be free music down there as well, which was great. The Portland Saturday Market, which was epic, free music on weekends but perhaps nothing as more renowned as the Oregon Country Fair in Veneta, certainly a Mecca of music and home of The Grateful Dead in 1972 and again in 1982 and almost in 1992, although that never happened.

Was there a venue that you frequented or was there a job at the venue that you were curious or interested in?

It wasn’t really like that for me. I was always into music and when I was a teenager, I went through a lot of musical evolutions personally. I started out a fan of heavy metal, the first concert I ever saw was Judas Priest followed shortly thereafter by The Clash and AC/DC. But I probably embraced The Grateful Dead around ‘85 or ‘86 which was a life changer for me as well as rap music. Discovering NWA was a life changer for me. But the venue we booked shows at was a place called Starry Night, which is now known as The Roseland Theater. But as a kid it was called Starry Night. And there were a handful of other places where bands played. But I didn’t get into the aspect of live aspect of music until I was in college.

You started booking music in college. How did you enter that world?

I answered a classified ad in my college newspaper at the University of Oregon for a job with an organization called the EMU. There were different student coordinators, including somebody who did national concerts. I thought that sounded cool and I applied. I had to interview with 25 other people. After I had been there for a year and did a decent job, they kept me around, but I had to go through the same process.

I was on the front wave of some of the first generation of jambands. I brought Phish to the W.O.W. Hall on April 4, 1991. I brought Blues Traveler to Oregon for the first time—Widespread Panic and many other bands. One of the last shows I did before I graduated was with Phish at the Hilton Ballroom on Earth Day ‘92.

What was your first job in the music business and what led you to that job?

My first job in the music business was being a runner for Bob Dylan. And what led me to that; well I was working for the promoter Double Tee Concerts, which is still there. They were working for Bob Dylan and what happened was I applied for this job booking bands on campus and I didn’t know what I was doing. I had to teach myself how to book a show and budget a show properly. The first show I ever booked was Arlo Guthrie

at the EMU ballroom and I sold the show out in advance, which was great, and I think it lost $5,000 of the school’s money. I truly just made up budgets. I thought that $250 sounded like a reasonable amount of money for sound and lights and the sound company gave me a bill the night of the show for $2,500 and I learned a tough lesion.

But in doing that I befriended the Double Tee, who were a major area promoter, they were also the people who brought The Grateful Dead to Eugene when they played. I was a big Deadhead at that point and what sparked my motivation for getting into the music business in the first place was figuring out how to get myself Dead tickets without waiting on a line. So that led to an opportunity to work for them when Dylan was at the Civic Auditorium in Portland and I was a runner for Al Santos who was Dylan’s longtime production manager and still is. I was 15 minutes late for my first job in the music business and I was never later again.

How did you transition into the music industry after you graduated?

I ended up moving to Vancouver and joined MCA Concerts. I worked for Jay Marciano. Today he is the head of AEG Live, but he started with this company in Canada. They were active in Toronto, Vancouver and in between, but they were going to break into Portland, Seattle and Eugene, and places like that. The first thing they had done was book a show at a little venue in Portland that no longer exists called the Portland Underground with the Smashing Pumpkins. The booking agent at CAA for Smashing Pumpkins, who was a friend of mine, had said to the MCA folks, “You should talk to this kid I worked with in Eugene. He’s very bright—he can work on all the stuff for you that’s under the radar.” They wanted to do this show and come into the market without making a lot of waves. I had everything handled and we sold out the show and it was a big success.

That led to another conversation and I drove up from Eugene to Tacoma where I met Jay Marciano and some other folks. The conversation went from, “We’ll touch base in September” to “I’m going to send you a plane ticket to Toronto next week. I’d like to meet with you more formally in our Toronto office.” Then we had a great meeting that manifested into a job opportunity in Vancouver, which was challenging because I was an American moving into a city and a country that I had never lived in before. I was trying to make my way in the world and it was a hard path, but it was ultimately a good one.

What was that first job you had in Vancouver?

I guess they called it Alternative Talent Buyer so I was sort of a club buyer, I was responsible for booking a club but it wasn’t Pete and The Wetlands. I booked club level bands that were young and I booked bigger bands over the course of my career because I grew with my bands. It was a time in history that being there with artists early seemed to matter more than money. It was also a point in time in Vancouver where promoters didn’t control the venues at that point. Almost every venue was an open venue, a third party venue, whatever you want to call it, a club that anybody could rent. They had enough buyers because they were open 7 nights a week. The in house people would book the local regional stuff and then national promoters would flash the national talent. But it was tough because I was an American living in Canada and I had to find the dynamics of being an outsider and tried to adapt and be accepted.

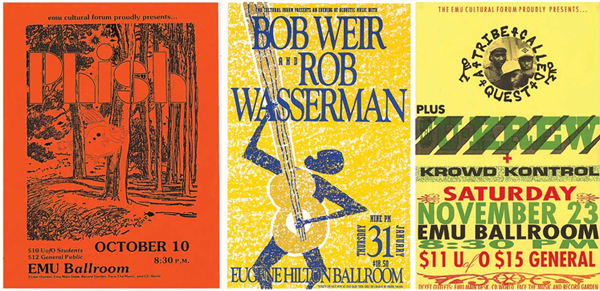

Show posters from Jason’s Oregon days

What was an early lesson that you learned in your career?

Two of the most important ingredients for success in the live music business are passion for music and attention to detail—paying attention to the details and on the day of a show

living up to whatever you had said to an artist or agent or manager in advance.

I remember one time that I worked with a great indie band called Cub. We agreed that the tickets at the door of the show would be $9, and I think I charged $10 because it was easier from a transaction point of view. But that’s not what we agreed to—and they were really upset about it and I handed everybody a dollar back on the way out. I stood at the front door and handed out loonies, which are a Canadian dollar coins. That was tough and it was a good lesson.

Talk about how you came to work for Live Nation.

After working as a promoter, in 1997, I left to go work for Blues Traveler. Dave Frey, their manager at the time, was running the H.O.R.D.E. festival and he was at the point where he needed to make a decision—either be the manager of the band and have somebody run this festival day to day, or focus on this festival and give up being the manager of the band. So I moved to New York to become the general manager of H.O.R.D.E. I joined them in ‘97. We had Neil Young & Crazy Horse, Morphine, Primus, Beck, Wilco, Sheryl Crow and all kinds of bands on that tour that year. In ‘98, I helped set up the tour and cut the deals for Blues Traveler and Ben Harper.

It wasn’t too long after when my old boss had called me up and said, “We never should’ve let you leave. We need you back; but we don’t need you in Canada. We could really use you in Denver.” Then, Dave told me they were talking about selling the festival to Delsener/Slater, so I thought, “OK, there’s the evil I know and the evil I don’t know.” I decided on Colorado where I worked for House of Blues Concerts.

The competition was fierce with Chuck Morris, Don Strasburg and Brent Fedrezzi, who had over 100 years of experience between them, but they were my friends and I admire them to this day. Chuck Morris was instrumental in getting me on Live Nation’s radar. At the time, Charlie Walker—who was running Live Nation—hired me to come work for him. I joined Live Nation in the spring of 2006, about six months before they bought House of Blues, so that was great timing for me. I was living in Los Angeles but booking concerts in Denver, and that made little sense so I moved back to Denver. Eventually, I made the move to New York in December 2007, and I’ve been here ever since.

Can you talk about your show day routine?

My show day routine starts with me re-familiarizing myself with all the particulars of that field. Going over where I happen to be at with ticket sales, re-familiarizing myself with the budget and expenses so I know what I’m walking into and when I get to a venue there’s many people I’m interacting with. I‘m interacting on the artist side with the production manager, the tour manager and the accountant, making sure everybody’s taken care of. I’m speaking to my production manager to get a sense of how the day is going not only in the sense of overall vibe and cooperation but the ins and outs of the size of the production and the crew and what’s working and not working. It could be something as easy as, “Hey we sold out but we figured out how to get 300 more seats to sell because the sidelines are better than we thought” or it could be, “We’re not sure when the artist is going to go on stage tonight and we might hit some overtime and all the implications of that.” Speaking to the representatives of the venue and when I get to the show for me at this stage in my career as president of Live Nation New York I’m fortunate to have a great team surrounding me that allows me the freedom to shake hands and kiss babies so to speak. With that said I’m meeting with managers, and artists, and record label people in New York. One of the things inherent in NY is there’s always a large contingency of the industry folk at a show. Growing up doing these shows in Canada and Portland there weren’t as many. A show on a Tuesday night in Denver is a show on a Tuesday night in Denver. On a Tuesday night in New York I couldn’t even tell you how many people are showing up at the Kanye West show but there will be a lot of them.

Where are you when the shows going on?

I’m hopefully standing on the side watching the band play unless there’s anything that will require my attention. I like to take as much time as I can to actually watch the artist perform. I look at shows now in a different lens that I did as a kid. I’m looking at the audience, I’m looking at the production, I’ll often walk around the venue and see if people are waiting in line to buy T-shirts or not or looking for hot dogs and pretzels and things like that. Just trying to familiarize myself with everything. In particular when I do shows in the summer at Jones Beach there’s not a show I do that I don’t go out to the merchandise booth and watch kids outside buying T-shirts and talk to our merchandiser because you can learn a lot about an artist and fans committed to that artist by how many people are buying merch.

You do so many high profile shows and to hear you go about it so seriously I think it really comes across that way to the fans.

I think so. I’ve made various friends over the years. One of the high points of my career, there was a couple I’ll never forget that until this day means the world to me. I don’t know 15 years ago, early on I developed a professional relationship that turned into a friendship with Snoop Dogg and his agent. At the time when I first started working with him, he was on No Limit Records which was Master P’s label and I wanted to do a show at my big amphitheater in Denver and they wanted somewhere else. His agent was like “10,000; we’ve never played that big. What makes you think you can do that?” and I just believed in it. I convinced them to do it and it was a huge success and we sold 12,000 tickets and that became the friendship. Over the years we did all kinds of shows.

A few years go by and I’m still in Denver and the agent calls me up and says, “I got a weird one for you…Snoop has never played the Apollo Theater in New York. He told me he wouldn’t do it without you so I need you to figure out how to promote Snoop at the Apollo Theater.” I was in Denver and there were all these territorial issues and things like that and I had to go figure out how to get this done, which I did. At the time I did it with John Scher, who’s a legendary promoter in New York. At the time he was managing Bob Weir and Bobby was my hero and I was close with him for a moment in time and I called up John like, “I know this is weird and can we do this thing together?” and he was very kind and gracious to me and we did two nights at the Apollo with Snoop and Ice-T. It was memorable. You get things like that very often.

Also, I did these thing years ago that was big for me, bringing electronic dance music to America. Working with Swedish House Mafia and bringing them to Madison Square Garden was very important and exciting because as a young guy there’s not too many opportunities at this stage of the game to do something at MSG that has never been done before. That was a big one. A shot heard around the world when EDM took off. Other than that, I had to pull the plug on acts and stuff like that with curfews. That wasn’t fun.

As the promoter it probably all comes back on you.

Yeah, I did it one time to Lenny Kravitz and we had this chat beforehand and he said, “Don’t worry about it I’m just going to play until you pull the plug,” and so he did and I had to pull the plug in the middle of “Fly Away” which was his big song at the time and he was so pissed as If the conversation never happened. Sometimes there are penalties and you need these strict curfews and if it’s 11 o’clock there’s no argument.

Can you talk about what your best day is like and what your worst and most stressful day is like currently?

The best days now are the ones where we get to celebrate music with people and our friends, my family here at Live Nation and ultimately the fans. There’s one thing for me that hasn’t changed in 20 years or however long I’ve been doing this, I can tell you unequivocally my favorite part of a concert, any concert, every time doesn’t matter who’s playing the best part of a show is that first moment when the lights go out and the crowd goes crazy. That moment makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up every time. It’s what I live for. The best part of it is certainly having great events that are epic and being in New York working with the best venues in the entire world is humbling and a privilege. It’s a privilege that I get to promote shows at Madison Square Garden and Carnegie Hall, the Barclays Center, Radio City Music Hall, and the Beacon Theater. These are epic venues. You can go anywhere in the world and I say I put on a concert at Madison Square Garden and they know what that is.