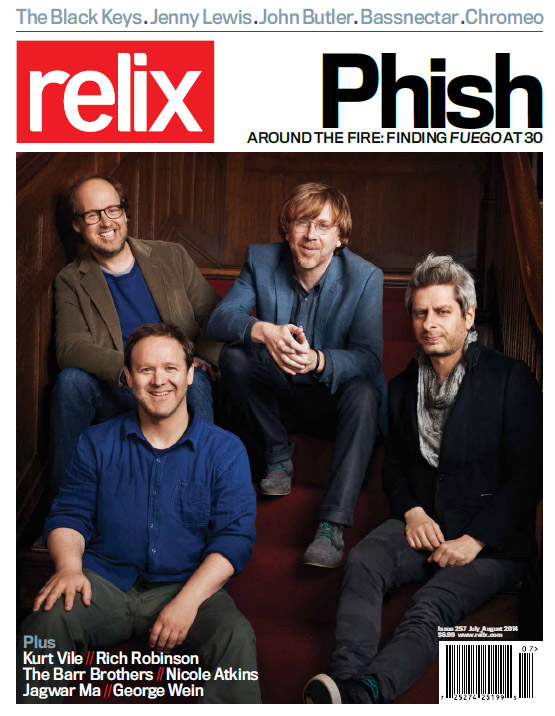

Throwback Thursday: Around the Fire with Phish

On the eve of Magnaball, we revisit last summer’s Phish cover story.

“Fire has always, throughout human history, been at the center of communities. People gather around the fire and talk or sing or connect,” Phish guitarist Trey Anastasio elaborates in reference to the title of the group’s new studio album, Fuego.

The animated musician then pivots from the Spanish meaning of the word to its usage as the French automobile name-checked in the title track, while accentuating the rapport between the band and their steadfast supporters.

“I love being able to sing, ‘inside your Fuego, we keep it rolling’ because it’s the Phish community that’s the heart and soul of what we do. We, Phish, keep it rolling, but what we do is inside of your Fuego. I like being able to think of that as we sing that line.”

However, while the group’s fans do have a place in the story of the new album, at Fuego’s core is the kinship between the four band members, estranged—if only musically—for a period of five years and now, five years after their reconciliation, pushing forward with a new collective enterprise.

“We are communicating better as a group than we ever have in our career,” keyboardist Page McConnell explains. “We are probably better friends than we ever have been collectively. So we had an idea for a pretty cool challenge and a fun way to involve everybody and take things to the next level. As it turned out, it’s become hugely exciting to us. We’ve been going for 30 years, and it’s really pretty remarkable at this point in our career to dive into an altogether different approach to songwriting.”

Since McConnell is not given to hyperbole, such a statement underscores the creative development both generated and reflected by Phish’s Fuego.

In October 2012, a few weeks after completing a 33-date summer tour, Anastasio, McConnell, bassist Mike Gordon and drummer Jon Fishman convened in The Barn, Anastasio’s Green Mountain recording studio, for a songwriting session that was unlike anything they had attempted in their career—an extensive collaborative effort from the music all the way down to the lyrics.

The band’s aims were relatively straightforward. “Our goal,” McConnell explains, “was to come up with a collection of songs that we would be able to play. We weren’t quite sure if we were making an album or going on a songwriting expedition. For a long time, we thought we won’t release it as an album, we’ll release it as a live video stream. There were all sorts of conversations about what the medium would be—how we might release it.”

The starting point for all of this was improvisation. Looking back from a distance of 18 months, Gordon remains flush with enthusiasm. “This was exactly what I had been hoping for a decade, we got into a studio and jammed,” he reveals.

“What happens, especially after 30 years of chemistry, is my fingers will play bass notes that fit better than if I were consciously thinking about it. I might take a few notes out of the bar of the pattern or I might change them in strange ways that would be unexpected for my conscious mind. So if a song germinates from that beautiful chemistry of the band playing itself like an Ouija board in the middle of a jam, then the fabric of the music that is going to be born of this thing is true to our souls. That’s what I really like about it.”

To a degree, this effort paralleled the sessions that yielded the songs that appeared on 1998’s The Story of the Ghost and 1999’s The Siket Disc, in which the group generated material together through live improvisation.

Gordon recalls that during that era, “We would go at 5 p.m., and jam for 12 hours until 5 a.m. with lots of breaks—until sunrise. We did it at Bearsville [Studios in New York] a couple times and we did it in Seattle with Steve Lillywhite one time. I love The Story of the Ghost album—or I used to think of it as one of my favorites—simply because I felt more of the process than the other albums.”

That process proved all the more inclusive on this occasion, as McConnell remarks, “While some of the intentions were the same, this one was more fully developed with just the four of us. With The Story of the Ghost, we took the jams and then dropped these words that [longtime lyricist] Tom [Marshall] and his friend Scott [Herman] had written on top of them. This one, we went in and started by creating music, but then we listened to it and developed song structures. Then, eventually, all four of us began inputting words.”

“We replayed everything so that it wouldn’t just be a Pro Tools mash-up, which so much music is these days,” Gordon details. “I thought that was a great direction. So as soon as we had a jam that we liked, we replayed it [and said], ‘Let’s take this vignette and use it as a B-section to this other one and, while we’re at it, let’s make up a little ascending chord progression to help tie them together.’ When you’re relying on Pro Tools, you get locked into the way it looks on the screen. But if you’re replaying, you’re starting from scratch every time. You’re using your ears and you’re using the muse freshly over and over again and you’re constantly letting go of what it was. That was pretty cool.”

Beyond their studio jams, the band also provided a similar treatment to a series of archival improvisations curated by the bass player. He scanned his journals, listened to live recordings and introduced selections drawn from performances between 2010-12, along with one sequence from an exercise at a 1993 band practice. (“I had saved it over the years as my favorite little gold nugget of possibility because every time we switched the patterns, it sounds like a new, interesting song and the rhythms and the spirit are infused with this vitality. So I took a few moments out of that.”)

When asked whether he could pick out any of the original songs in the new tunes that share a musical DNA, he clarifies, “No, because usually it’s between five or 10 minutes or more into a jam, where it’s a fresh grouping of chords, melodies and rhythms. I wouldn’t be able to predict it because it doesn’t ever sound like the song that it’s coming from—it’s usually a departure.”

Then came the marriage of words and music. Although Phish has collaborated on a multitude of instrumental passages over the years— and the four members continue to do so on a regular basis in the concert and rehearsal settings—they had not shared much respon- sibility for this aspect of songwriting, beyond a few comic numbers about crew members and mutual acquaintances written before their 1997 European tour (“Carini,” “Rock A William” and “Walfredo”).

Indeed, Gordon can remember his own awkward reaction more than two decades ago when John Popper stopped by to co-author a song. “It was around the H.O.R.D.E. era, back when the rest of the band lived in Winooski, [Vt]. John Popper took out a notebook, sat on the staircase, lyrics were being thrown around, and I remember thinking, ‘Ooh, this is weird. I’m not supposed to be around when this part is being done.’ Of course, I had written a couple of my own songs but in terms of the group, I kept thinking this was almost taboo, never mind helping, but even being a witness to it. But now, fast forward to really wanting to get into the sharing of that process. Of course, Page and I now have much more experience to bring to the table.”

The table metaphor proves to be fitting, as the band placed an emphasis on comestibles and conversation, typically to the exclusion of anyone outside of Phish.

With notebooks in hand, the musicians ascended to The Barn’s cupola. Reached via a catwalk and a motorized lift, this was the first time that they had occupied the space to work as a foursome. Here, a particular photograph or story served as a starting point for 10 minutes of individual writing, which the bandmates then shared in a circle, while identifying the lines that felt resonant.

On other occasions, they passed around a microphone for a stream of consciousness approach, to see what came to mind and if that could perhaps become a source of inspiration.

Anastasio reflects, “The best part of the collective lyric writing experience, for me—other than the simple fact that it gave us the opportunity to hang out together—was seeing how inclusive every- body was. If two or three people got going on an idea, someone would always pull the others into the conversation, and say, ‘What do you think? Do you like where this is going?’”

“It was all very loose and experimental and there wasn’t any formula to it. ‘Waiting All Night’ was inspired by a pinball repairman that we all happen to know who just sort of unloaded, telling us about all these problems he was having,” McConnell illustrates. “It was just somebody had a story, so let’s write a song about that. There’s a lot of emotion but it’s our interpretation using these stories. There was also a photo of this girl sort of dressed like she was going to go to a Renaissance fair with Viking warriors and animal heads, and there was a whole song that didn’t make the album with that stuff.”

Wingsuit became the working title for the emerging body of material, McConnell attests, “not because it was necessarily the first thing we wrote, but because it was the first song with some substance to it, some emotional weight and not just silliness or some words over a jam. When we did that one, I thought, ‘OK, we really might be able to write some great songs,’ so it was always an inspiration.”

While Gordon was downright enamored with the results, it didn’t always come easily. Over the past decade in particular, the bassist has developed into an accomplished songwriter, and if certain critics once dismissed his contributions as novelties or odd for odd’s sake, then that era is long past. Nonetheless, he admits that the group setting could be trying.

“What makes it hard is lyrics are a personal thing both in terms of what they mean and the process of putting them together. Then, to have to share, that can be a little bit of a challenge for some of us who are a little shyer in a group, where it might be easier for Trey because he’s written so many incredible songs over the years, and he’s had so many songwriting weekends with Tom. He’s very animated and alive and alert in that mode. Often, when he speaks, he stands up and starts dancing around.”

When pressed to name a particular triumph of collective lyric writing, Anastasio points to “The Line,” which “felt like a bit of a triumph to me, and a bit of an eye-opener as well. What fascinated me was that the more honest, detailed and specific we tried to make it, the more universal it became. We had a photo of Darius Washington Jr. standing at the foul line that we looked at as we wrote, and we were really trying to climb inside of his head. [In 2005, with a trip to the NCAA tournament on the line, the Memphis basketball player missed two consecutive free throws with no time on the clock, and his team lost the game as Washington crumpled to the floor in tears.] I had been pushing pretty hard on writing this particular song because I could relate so much to his experience of crashing and burning publicly. Of course, we’ve never met, but I wondered if this event, which felt like such a disaster and an embarrassment when it was happening, ultimately became a gift for him a few years down the road. That was certainly true in my case— you learn what’s actually important in situations like that.”

For Anastasio, this seems to mean hunkering down, closing ranks and recommitting to kith and kin. (For Washington, it’s a basketball career in Europe, where he now plays in Turkey’s pro league.) Following Anastasio’s 2006 arrest on drug charges—two years after Phish’s “farewell” performance at its Coventry festival—a 14-month rehabilitation seemingly paved the way for creative fire and esprit de corps. His return to the stage with Phish in March 2009 amid a collective exuberant headspace, later allowed for collaboration with a producer whose work the band had long admired.

“At this stage in my career, when I see somebody who’s miserable, I just run away from that,” proclaims producer Bob Ezrin, whose projects over the past 40 years have included celebrated albums by Pink Floyd, Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed and even KISS. “It’s too difficult and I’ve spent more time than I care to with people who are unhappy with this amazing thing that we get to do. So when I see a group of people who are doing something and are happy about it, then that’s an attractive thing from the start.”

Ezrin’s attraction to Phish began in earnest last July following a phone call to gauge his interest. While The Barn material had originated without a specific medium in mind, the group now decided that it merited a proper album release, nurtured by an additional set of ears.

The producer concedes, “While I knew something about Phish, I didn’t know about the power of Phish. I didn’t know that much about their music except for a couple of their records. So when I learned that the guys had occasionally spoken about working with me over the years, that was a complete surprise. I told them: ‘I really wouldn’t think of this for me, it’s not something I have ever done before’ but that I would be very interested in at least seeing the band live.”

Gordon had initially expressed reluctance at bringing in an outsider to touch the material they had developed in Vermont. “The band had a meeting over dinner where the three of them said, ‘These demos are great but they’re just demos. Let’s get a producer and maybe we’ll replay them or re-record them.’ I thought they had such a floaty flow and not only couldn’t be beat, but I had never in my life heard Phish like that before—being so organically Phish, including how they were recorded with only one other person in the room. So I had trepidation about replaying anything and about getting a producer who wouldn’t even listen to those after we’d done this beautiful thing, but I was wrong and they were right.”

Despite his initial doubts, out of his respect for his bandmates’ sentiments, it was the bass player who supplied the connection to Ezrin. Throughout the process of making the new Phish album, Gordon was also working on his own solo release, Overstep. While discussing the Phish project with Overstep producer Paul Q. Kolderie, whom Gordon also had targeted as a potential match for the group, Kolderie suggested Ezrin. Long after receiving his first producer’s credit at age 21 for Alice Cooper’s Love It to Death, Ezrin remained an active presence in the recording industry.

Phish had bandied about Ezrin’s name in the past, without any real expectation that he was a realistic option. Gordon cites The Wall as his favorite Ezrin production while McConnell names Lou Reed’s Berlin and Anastasio concurs, adding, “We used to listen to that record a lot in the Winooski house in the ‘80s and dream of working with Bob.”

So on Tuesday, July 16, 2013, Ezrin attended the group’s performance at the Verizon Wireless Amphitheatre at Encore Park in Alpharetta, Ga. He admits to an ulterior motive, as his 18-year-old granddaughter lives in the area. More of a hip-hop fan, she accompanied him to the venue a few hours before the band hit the stage and had intended to make an early exit but the producer explains, “She remained because it was such a wonderful, exciting vibe. What’s more, I stayed and watched every song and that’s a precedent,” he chuckles. “I don’t stick around much because I’m a quick study. I can see three or four tunes and say I get it but I loved the energy so much that I didn’t want to leave.”

The next day over lunch, the five principals solidified a mutual commitment that would lead Ezrin to The Barn in early October for pre-production on the album soon to be formerly called Wingsuit.

Page McConnell was Ezrin’s first point of contact Phish. The producer recalls, “I met Page before the show and we spent some time together and I met the other guys in the hallways and, after the show, I met Trey. They seemed very centered and very articulate and smart and pretty laid-back and genuinely happy.”

McConnell’s role as the initial band member to squire Ezrin through the world of Phish would seem to reflect a relatively recent change within the group. From the audience perspective, McConnell seems to be taking a more vocal role, at least in terms of crowd interaction, previously the near-exclusive province of Anastasio. The keyboard player acknowledges, “I am talking more onstage for sure than I was a few years ago, largely because Trey has encouraged me to say something. There’s not a lot of banter between ourselves and the audience, but it is nice to have a little bit of dialogue with the audience and I enjoy doing it. But I really like it when Trey talks. I like it when any of them talk. I like it when Mike talks. It’s rare, but occasionally he’ll say something and that’s often my favorite part of the show.”

Then after a pause he adds, “I suppose, in a lot of ways, Trey is perceived as the leader of the band and, in many ways, he does lead the band, but really we all lead the band in our own way. It’s much more democratic and egalitarian than it may appear to be. We all think of each other as equally important and equally valuable and each of our voices should be equally heard on any given issue, whatever it is. It just happens that Trey counts off the songs and sings most of them and has written most of them. That aside, he’s a good bandleader—he’s got a great personality for it—but we all take leadership roles in areas that might not be as obvious to people. I tend to be more involved with certain business stuff, but really any of us are the leaders in any particular conversation and in any particular improvisation, any of us can be leading the jam. It really is very democratic.”

Still, as for the initial conversation with Ezrin, he offers a polite laugh then demurs, “In terms of meeting Bob, I just happened to be the first to catering—that’s how I recollect it. I knew he was coming and I was waiting for him but I think I was first because I was hungriest.”

Ultimately, these particulars are incidental to McConnell, secondary to his belief that “it just seemed it was the perfect point in our career to meet him and maybe it was the right point in his career to meet us. We were really lucky to make the connection.”

Bob Ezrin arrived in Vermont during peak foliage season and his delight at the vistas soon matched his perspective inside the studio.

“First off, The Barn is just off-the-charts magical. It’s crazy,” he recollects. “I drove up the driveway looking out over the mountains, and it’s just breathtaking. Then I go up the stairs and look into this Arts-and-Craftsy beautifully appointed recording space that just felt so natural and nurturing and inspiring. The other side of it was, here’s a band that can play absolutely anything they think of. For a guy like me who has been doing this as long as I have, to be able to work with a band that moves at that speed, it’s not even unusual— it’s the kind of thing that never really happens and it’s such a joy when it does.”

His first charge to the group was for them to play him everything. Rather than focus on the material they had written together in the very space where they now gathered, he wanted to hear any recent material they had created individually or collectively, without any backstory, so that he could gauge each piece on its own merits. So Phish presented him 48 selections, which included original songs that the band had debuted, new material yet to appear in the live setting, and some pieces still in progress that lacked lyrics or sections. Ezrin listened to it all and winnowed down the list to a baker’s dozen. They began work that same day.

This was the moment when the project coalesced into something beyond the initial songwriting expedition that had set the process in motion a year earlier, and took on a new identity as Bob Ezrin’s Phish album. While the majority of the producer’s picks had origi- nated at The Barn, a number of them were compositions penned separately by Anastasio, Gordon and McConnell.

What’s more, Ezrin was not content to let the songs live as originally constituted. As they began work on the final selections for the album, he became an active participant in the process.

“He didn’t want to leave the limits of friendliness and, ultimately, all of the decisions from tiny to big were going to be left up to the artist but, within that context, he pushed the limits of ‘OK, we need a chorus’ or ‘This needs to slow down’ or ‘Everything needs to stop when the drum fill happens,’” Gordon recalls. “When we’d play in the studio, he’d be walking between the four of us listening and he might go up to Fish and say, ‘What is this, a race?’ trying to pleasantly tell him to slow down. Or he would say, ‘Trey, after the second chorus where you go up high, not the highest note, the second to highest note, I realize that there should be this whole other instrument that should come in right there and that up note should be minor instead of major’ and some very specific stuff that made me think, ‘Wow, this guy is really listening astutely,’ but even so, he didn’t let micro- vision get in the way of seeing the overall picture.”

McConnell adds, “He was right in there with the lyrics and the beats and the chords, but especially the lyrics. Really, more than anyone we’ve ever worked with, making me work for every line in every song, [asking], ‘What do you mean? What are you trying to say?’ But that’s what a good producer does. He just does it a little bit more and he’s better at it than most of the people that we’ve worked with.”

One can hear Ezrin’s influence in the modest variations between the original lyrics to McConnell’s wistful, reflective “Halfway to the Moon,” which Phish debuted in June 2010, and the version that ultimately made it to the new album, as these small changes lend emotional heft.

Gordon adds, “There may have been a text or a phone call saying, ‘Wow, this guy is really being bold here,’ but he won over our confidence.”

While work continued apace, the clock was ticking, with Phish set to open a tour on October 18 and to perform a special three-set Halloween show two weeks later in Atlantic City.

Halloween is sacrosanct to Phish fans. Ever since 1994, when the quartet covered The Beatles’ “White Album” at New York’s Glens Falls Civic Center, the band’s musical costume has remained an October 31 tradition. Although Phish has not always promised a Halloween cover album, in every instance since ‘94,when the group has booked a show on that date, it has delivered one.

2013 would be different.

As they entrenched themselves in pre-production, anticipating the studio sessions to follow in Nashville at the conclusion of the tour, the band members began to question whether they had the available hours and energy to work up a Halloween cover. More significantly, however, their hearts just weren’t up to the task. They preferred to devote any free time to their own work in progress rather than another band’s fossilized collection of songs.

So they flipped tradition on its head and rather than cover another group’s recording, they opted to present a yet-to-be recorded album of their own.

“I thought it was a brilliant idea,” Ezrin comments. “I heard that stuff in the rehearsal room so I knew how good they were and how well the stuff would sound. I thought it was brave, only because it broke precedent, but I thought it was really going to excite the audience.”

So on October 31 at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, Phish’s second set consisted of 12 song debuts, all of which were to be tracked with Ezrin a few days later as Wingsuit. Six of the compositions were full-band collaborations (“Fuego,” “The Line,” “Waiting All Night,” “Wingsuit,” “Wombat” and “You Never Know”), four were written by Anastasio and Tom Marshall (“Amidst the Peals of Laughter,” “Devotion to a Dream,” “Sing Monica” and “Winterqueen”), and two were from Gordon and Scott Murawski (“555” and “Snow”). The band did not play McConnell’s “Halfway to the Moon,” which also was in consideration, opting to focus on premieres. (The next night, Phish performed the tune after Anastasio explained that McConnell’s original was “at the top of the list of the songs that we want to be on the new album.”)

The band members all suggest that per- mitting their audience to share in the process seemed more meaningful and true to the moment, although they recognized that there might be few detractors.“If we were to play a Halloween album only because that’s what everybody expected, it would feel kind of lame— that’s never been the Phish way,” McConnell asserts. “We’ve always done what we thought was the right thing to do. We love our covers, but we are Phish and we are the only ones who can play this music, and that’s why I think people come to see us. We went out at New Year’s and we played four nights of completely original music without repeating a song. We didn’t play covers and I really liked those shows a lot.

“So were there going to be people who would rather hear Dark Side of the Moon or Led Zeppelin I or Lamb Lies Down or whatever they thought we should be playing? I guess, but we’re Phish and we’ll continue to celebrate ourselves in this 30th year. I’ve embraced that more and more as the year’s gone on. This was part of that decision.”

As for celebrating the full sweep of Phish, not only did the group deliver all original material during the year-end run at Madison Square Garden but also, on December 31, the band’s traditional New Year’s Eve gag found them performing atop a small box truck in the middle of the venue, utilizing hockey stick micro- phone stands as a nod to the set-up they had employed at their initial performance on Dec. 2, 1983 at the University of Vermont in the Harris-Millis residence hall cafeteria of freshman Michael Gordon.

In reference to the New Year’s Eve set, Anastasio shares his memories of Phish’s live debut, more than 30 years ago.

“It comes down to a feeling—a feeling that I get that’s never gone away. Something happens when you show up for soundcheck, and you plug in your amp, and you do that first whack on the strings and that sound comes blaring out of the amp, and it’s just, ‘Pow’— electric guitar. I love it so much and I always have. I live for that moment. Then someone else walks up onstage, maybe Fish sits at his drums, and ‘Blam,’ starts playing and they join in and now we’re together, playing, linked. Then the audience comes in the room, and you make eye contact or just play off the way they are dancing. Maybe I’ll see a shadow way up in the balcony, dancing or just standing and moving a little in a certain way. I’ll be watching and responding to them, and the music ebbs and flows in response, and you know that they can tell that they are having an effect. It’s the most magical feeling on earth.

“So what I remember about that first performance is that we plugged in, and I got that feeling. The ‘audience’ was like two people total—my girlfriend at the time, Kristen Barber, and my roommate, Pam Peck-Ketcham. They were dancing and it was amazing. I don’t even remember much else of that night, but I remember that. Then, this past New Year’s, we got to stand in the middle of Madison Square Garden and I remember connecting with a bunch of people that were right up close to the truck. That feeling never ceases to amaze me.”

Gordon offers his own comparison of that first show with the MSG set, spiked by his signature dry humor. “I think it’s well- known that at our first gig, they wanted us to stop so they could play their Michael Jackson tape. So that was different—people didn’t want us to stop so they could play their Michael Jackson tape…”

When pressed to deliver a state of the musical union address, McConnell remarks, “I feel like we’re still breaking new ground in finding new ways to communicate. I don’t listen to Phish very much, but occasionally, I’ll be in a rental car that has SiriusXM and I’ll turn to Jam_On and some Phish song will come on. Just recently, I heard this ‘Tweezer’ from Hampton, I think from last fall, that I really liked a lot. Or that ‘Harry Hood’ at the Greek Theatre or some of the jamming at the end of the summer—everyone talks about Tahoe or Bill Graham.”

McConnell acknowledges that following the group’s return in 2009, it took a little while to reconnect musically and that they may have been a bit tentative.

“First of all, I don’t think anyone thinks Coventry was the greatest show we ever played, so why do they think we’re going to come back and play the greatest show at the next show? Some might argue we were on a downward slide, so didn’t we turn it around? Maybe that’s more of how it should be looked at,” he quips. “But even in the couple years before we broke up, when we had some struggles, there were still moments of live improvisation that were kind of mind-blowing to me—maybe not as consistently, but there were still those moments.

“When we came back, we weren’t trying to play tentatively, I can assure you, but I would agree it started to get better for me a year and a half into it—I started to feel more of a looseness. It takes a while to get back in the saddle sometimes. If two people were to split up, a boyfriend and girlfriend, and not see each other for five years and then, on their first date back, people were to say, ‘You guys feel a little tentative? What’s up with that?’ Well, if they decided to break up, there were problems leading up to that. So we needed to go way back.

“What ended up happening for me was getting back to the place we were in ‘87, ‘88 and ‘89—that kind of comfort and pure joy of being with each other and having fun and making music for people, which is why we got into it in the first place. It took a little while to relearn that and to remember that and to get back there, but we did. So to me, it’s even more fun than it was at some of those earlier shows that were fun and carefree.”

This was the spirit that Phish brought to bear on Halloween and this was the spirit that carried over into the recording sessions a few days later.

“We decided that we were going to make an album that was for Phish, by Phish as they are today,” Bob Ezrin explains. “We wanted to make an album that captured them at the stage they’re at now. So I said, ‘If a song is nine minutes long, I’m all for it.’”

After Atlantic City, the band migrated to Ezrin’s Anarchy Studios. He had watched the Halloween performance from his Nashville, Tenn., office and determined that he would approach the tracking sessions like a live show. Phish would run through each song a few times and then move on, without agonizing over a particular four bars or playing anything so many times that it felt mechanical.

During the weeks to follow, the band checked in regularly from afar and occasionally from closer proximity, as when Anastasio returned for a “guitarathon” of overdubs.

Ezrin set to work building from the basic tracks, adding texture and tone while maintaining Phish’s energy and enthusiasm. The producer characterizes his ensuing dialogue with the group as affable and cooperative. “At the end of the day, anything that they really wanted got to happen and anything they didn’t really like got cut. I never would overrule the will of the band when the will of the band was expressed but as it stood, we didn’t have many situations where the will of the band was any different from the will of Bob.”

Ultimately, the final track listing differed slightly from the Halloween performance. “Snow” and “Amidst the Peals of Laughter” didn’t quite come together. While “Halfway to the Moon” made the album, “You Never Know” was deemed an imperfect fit. (“That was an early one where we really got into the lyrics and where the way the music flows feels very Phishy, but the artistic process is more about letting go than anything else,” Gordon relates.)

Meanwhile, the album’s nine-minute song came into its own to such a degree that the Halloween crowd-pleaser also became the title track. Nearly cast off at The Barn, “Fuego” had been refashioned at the very close of pre-production as a mash-up between a vignette, titled “Sailor’s Girl,” and a rawer iteration of the tune.

“Fuego” also supplied a teachable moment for Phish and their producer. Ezrin reveals, “There were a couple times where there was something I didn’t realize about Phish that needed to be taught to me. They did it in a respectful, gentle way but they were definite about it. We had a very long earlier version of ‘Fuego.’ I produced it up with a lot of really cool features but, at the end of the day, it wasn’t satisfying to them as a jam. They didn’t feel the conversation happened in an organic and proper way. I realized that for these guys it’s that conversation between them that defines who they are. So, they convinced me to go to a soundcheck version of it.”

No one in the group can pinpoint the moment when Wingsuit became Fuego, but they all agree that the transformation took place within a swell of emails that the band exchanged during the winter.

“It’s almost like the thing itself finds out what it wants to be and, at one point, it wanted to be Wingsuit and then, it wanted to be Fuego,” Gordon posits. “I do know that Fish had suggested that we reconsider Wingsuit at one point—with its theme of encouraging people to put on their wingsuit and take off—because that’s such a spirited sentiment. Fuego, with its fire, can be negative, but we were seeing it as a celebration in the way that fireworks involve fire.”

The duality of the word is analogous to the twin elements that Ezrin balanced in assembling the album. While the tracks manifest the vitality and spirit that initially drew the producer to the band, he also added richness and nuance to fashion an album that reveals itself with each additional listen, whether on expansive tunes such as “Fuego” and “Wingsuit,” or more concise selections like “Waiting All Night” and “555.”

“He did not get rid of that floaty Phish vibe that I was worried about losing,” Gordon reflects, “even though we replayed the songs and even though we used a click. I like to hear some production and tightening and he got right in there. I believe that every artist is, at once, a terrible, laughing joke and an incredible, potential maestro. It’s all about finding the balance.”

Fuego aspires to that sweet spot.

In crafting their new record, Phish made a commitment to take things full circle and distill the experience down to its essence, which is four friends playing together.

Although family commitments and a spate of musical projects from solo groups to orchestral collaborations to other alluring one- offs may vie for the band members’ attentions, Anastasio observes, “We communicate a lot. There are lots of group emails and texts. Yesterday there was, ‘Did you see the new Phish Food packaging? Cow in dress! Awesome.’ And the day before it was, ‘Did you see this link to The Strypes on Letterman? This band is too cool for their age.’ Stuff like that. Fish sends a lot of really long emails, often a little political. Page is becoming the ‘first responder,’ which I absolutely love, because I don’t want to play that role anymore. I’m grateful to him for taking the reins. Mike occasionally sends a one- word text that has me laughing for a week.”

Bob Ezrin offers a perspective wrought from his decades in the company of artists: “I know that there have been times, like in any long-term partnership, when there have been disputes and some- times a little bit of stress but, at the end of the day, these are four brothers who got together at the very beginning of their adult lives because they were a magical combination and that magic remains.”

McConnell maintains, “At this point, I feel that what we have between the four of us is so strong. Over the course of a tour, you’re going to have sweet rides and maybe a few valleys but I will never, for a second, doubt where everyone’s head and heart is and that we’re completely committed to each other and that we’re giving 100 percent to it all the time. I don’t think I can overstate how incredible it is to be at this point in our career and learn a completely new way to create. It opens up all sorts of possibilities for the future.”