Around The Fire with Phish (An Excerpt)

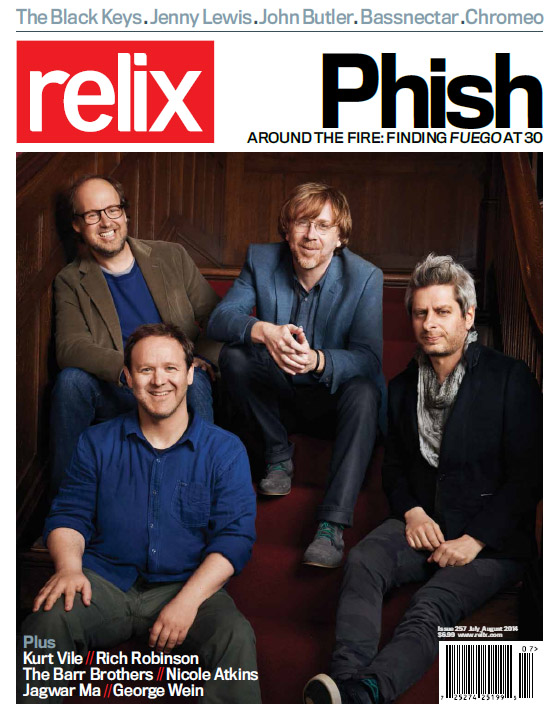

Today marks the official release of the new Phish album, Fuego. The band appears on the cover of our July_August issue, in a feature written by editor-in-chief Dean Budnick, which explores the process of recording the new record with producer Bob Ezrin (Pink Floyd, Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed), the decision to debut material on Halloween as well as the current state of the quartet. While the issue won’t hit newsstands for another two weeks, today we present an excerpt from the cover story. In addition, we’re offering a special discount on subscriptions that will include the July_August issue with the Phish on the cover. So check out the preview below and then head to our subscriptions page, where you can get a discounted year of Relix ($20) by entering the promo code: Phish.

“Fire has always, throughout human history, been at the center of communities. People gather around the fire and talk or sing or connect,” Phish guitarist Trey Anastasio elaborates in reference to the title of the group’s new studio album, Fuego.

The animated musician then pivots from the Spanish meaning of the word to its usage as the French automobile name-checked in the title track, while accentuating the rapport between the band and their steadfast supporters.

“I love being able to sing, ‘inside your Fuego, we keep it rolling’ because it’s the Phish community that’s the heart and soul of what we do. We, Phish, keep it rolling, but what we do is inside of your Fuego. I like being able to think of that as we sing that line.”

However, while the group’s fans do have a place in the story of the new album, at Fuego’s core is the kinship between the four band members, estranged—if only musically—for a period of five years and now, five years after their reconciliation, pushing forward with a new collective enterprise.

“We are communicating better as a group than we ever have in our career,” keyboardist Page McConnell explains. “We are probably better friends than we ever have been collectively. So we had an idea for a pretty cool challenge and a fun way to involve everybody and take things to the next level. As it turned out, it’s become hugely exciting to us. We’ve been going for 30 years, and it’s really pretty remarkable at this point in our career to dive into an altogether different approach to songwriting.”

Since McConnell is not given to hyperbole, such a statement underscores the creative development both generated and reflected by Phish’s Fuego.

In October 2012, a few weeks after completing a 33 date summer tour, Anastasio, McConnell, bassist Mike Gordon and drummer Jon Fishman convened in The Barn, Anastasio’s Green Mountain recording studio, for a songwriting session that was unlike anything they had attempted in their career—an extensive collaborative effort from the music all the way down to the lyrics.

The band’s aims were relatively straightforward. “Our goal,” McConnell explains, “was to come up with a collection of songs that we would be able to play. We weren’t quite sure if we were

making an album or going on a songwriting expedition. For a long time, we thought we won’t release it as an album, we’ll release it as a live video stream. There were all sorts of conversations about what the medium would be—how we might release it.”

The starting point for all of this was improvisation. Looking back from a distance of 18 months, Gordon remains flush with enthusiasm. “This was exactly what I had been hoping for a decade, we got into a studio and jammed,” he reveals.

“What happens, especially after 30 years of chemistry, is my fingers will play bass notes that fit better than if I were consciously thinking about it. I might take a few notes out of the bar of the pattern or I might change them in strange ways that would be unexpected for my conscious mind. So if a song germinates from that beautiful chemistry of the band playing itself like an Ouija board in the middle of a jam, then the fabric of the music that is going to be born of this thing is true to our souls. That’s what I really like about it.”

To a degree, this effort paralleled the sessions that yielded the songs that appeared on 1998’s The Story of the Ghost and 1999’s The Siket Disc, in which the group generated material together through live improvisation.

Gordon recalls that during that era, “We would go at 5 p.m., and jam for 12 hours until 5 a.m. with lots of breaks—until sunrise. We did it at Bearsville [Studios in New York] a couple times and we did it in Seattle with Steve Lillywhite one time. I love The Story of the Ghost album—or I used to think of it as one of my favorites—simply because I felt more of the process than the other albums.”

That process proved all the more inclusive on this occasion, as McConnell remarks, “While some of the intentions were the same, this one was more fully developed with just the four of us. With The Story of the Ghost, we took the jams and then dropped these words that [longtime lyricist] Tom [Marshall] and his friend Scott [Herman] had written on top of them. This one, we went in and started by creating music, but then we listened to it and developed song structures. Then, eventually, all four of us began inputting words.”

“We replayed everything so that it wouldn’t just be a Pro Tools mash-up, which so much music is these days,” Gordon details. “I thought that was a great direction. So as soon as we had a jam that we liked, we replayed it [and said], ‘Let’s take this vignette and use it as a B-section to this other one and, while we’re at it, let’s make up a little ascending chord progression to help tie them together.’ When you’re relying on Pro Tools, you get locked into the way it looks on the screen. But if you’re replaying, you’re starting from scratch every time. You’re using your ears and you’re using the muse freshly over and over again and you’re constantly letting go of what it was. That was pretty cool.”

Beyond their studio jams, the band also provided a similar treatment to a series of archival improvisations curated by the bass player. He scanned his journals, listened to live recordings and introduced selections drawn from performances between 2010-12, along with one sequence from an exercise at a 1993 band practice. (“I had saved it over the years as my favorite little gold nugget of possibility because every time we switched the patterns, it sounds like a new, interesting song and the rhythms and the spirit are infused with this vitality. So I took a few moments out of that.”)

When asked whether he could pick out any of the original songs in the new tunes that share a musical DNA, he clarifies, “No, because usually it’s between five or 10 minutes or more into a jam, where it’s a fresh grouping of chords, melodies and rhythms. I wouldn’t be able to predict it because it doesn’t ever sound like the song that it’s coming from—it’s usually a departure.”

Then came the marriage of words and music. Although Phish has collaborated on a multitude of instrumental passages over the years—and the four members continue to do so on a regular basis in the concert and rehearsal settings—they had not shared much responsibility for this aspect of songwriting, beyond a few comic numbers about crew members and mutual acquaintances written before their 1997 European tour (“Carini,” “Rock A William” and “Walfredo”).

Indeed, Gordon can remember his own awkward reaction more than two decades ago when John Popper stopped by to co-author a song. “It was around the H.O.R.D.E. era, back when the rest of the band lived in Winooski, [Vt]. John Popper took out a notebook, sat on the staircase, lyrics were being thrown around, and I remember thinking, ‘Ooh, this is weird. I’m not supposed to be around when this part is being done.’ Of course, I had written a couple of my own songs but in terms of the group, I kept thinking this was almost taboo, never mind helping, but even being a witness to it. But now, fast forward to really wanting to get into the sharing of that process. Of course, Page and I now have much more experience to bring to the table.”

The table metaphor proves to be fitting, as the band placed an emphasis on comestibles and conversation, typically to the exclusion of anyone outside of Phish.

With notebooks in hand, the musicians ascended to The Barn’s cupola. Reached via a catwalk and a motorized lift, this was the first time that they had occupied the space to work as a foursome. Here, a particular photograph or story served as a starting point for 10 minutes of individual writing, which the bandmates then shared in a circle, while identifying the lines that felt resonant.

On other occasions, they passed around a microphone for a stream of consciousness approach, to see what came to mind and if that could perhaps become a source of inspiration.

Anastasio reflects, “The best part of the collective lyric writing experience, for me—other than the simple fact that it gave us the opportunity to hang out together—was seeing how inclusive everybody was. If two or three people got going on an idea, someone would always pull the others into the conversation, and say, ‘What do you think? Do you like where this is going?’”

“It was all very loose and experimental and there wasn’t any formula to it. ‘Waiting All Night’ was inspired by a pinball repairman that we all happen to know who just sort of unloaded, telling us about all these problems he was having,” McConnell illustrates. “It was just somebody had a story, so let’s write a song about that. There’s a lot of emotion but it’s our interpretation using these stories. There was also a photo of this girl sort of dressed like she was going to go to a Renaissance fair with Viking warriors and animal heads, and there was a whole song that didn’t make the album with that stuff.”

Wingsuit became the working title for the emerging body of material, McConnell attests, “not because it was necessarily the first thing we wrote, but because it was the first song with some substance to it, some emotional weight and not just silliness or some words over a jam. When we did that one, I thought, ‘OK, we really might be able to write some great songs,’ so it was always an inspiration.”

While Gordon was downright enamored with the results, it didn’t always come easily. Over the past decade in particular, the bassist has developed into an accomplished songwriter, and if certain critics once dismissed his contributions as novelties or odd for odd’s sake, then that era is long past. Nonetheless, he admits that the group setting could be trying.

“What makes it hard is lyrics are a personal thing both in terms of what they mean and the process of putting them together. Then, to have to share, that can be a little bit of a challenge for some of us who are a little shyer in a group, where it might be easier for Trey because he’s written so many incredible songs over the years, and he’s had so many songwriting weekends with Tom. He’s very animated and alive and alert in that mode. Often, when he speaks, he stands up and starts dancing around.”

When pressed to name a particular triumph of collective lyric writing, Anastasio points to “The Line,” which “felt like a bit of a triumph to me, and a bit of an eye-opener as well. What fascinated me was that the more honest, detailed and specific we tried to make it, the more universal it became. We had a photo of Darius Washington Jr. standing at the foul line that we looked at as we wrote, and we were really trying to climb inside of his head. [In 2005, with a trip to the NCAA tournament on the line, the Memphis basketball player missed two consecutive free throws with no time on the clock, and his team lost the game as Washington crumpled to the floor in tears.] I had been pushing pretty hard on writing this particular song because I could relate so much to his experience of crashing and burning publicly. Of course, we’ve never met, but I wondered if this event, which felt like such a disaster and an embarrassment when it was happening, ultimately became a gift for him a few years down the road. That was certainly true in my case—you learn what’s actually important in situations like that.”

For Anastasio, this seems to mean hunkering down, closing ranks and recommitting to kith and kin. (For Washington, it’s a basketball career in Europe, where he now plays in Turkey’s pro league.) Following Anastasio’s 2006 arrest on drug charges—two years after Phish’s “farewell” performance at its Coventry festival—a 14-month rehabilitation seemingly paved the way for creative fire and esprit de corps. His return to the stage with Phish in March 2009 amid a collective exuberant headspace, later allowed for collaboration with a producer whose work the band had long admired…

***

There is much more to the story. Be sure to pick up the issue on newsstands in early July or visit our subscriptions page, where you can get a discounted year of Relix ($20) by entering the promo code: Phish. Your subscription will begin with the July_August issue featuring Phish on the cover.