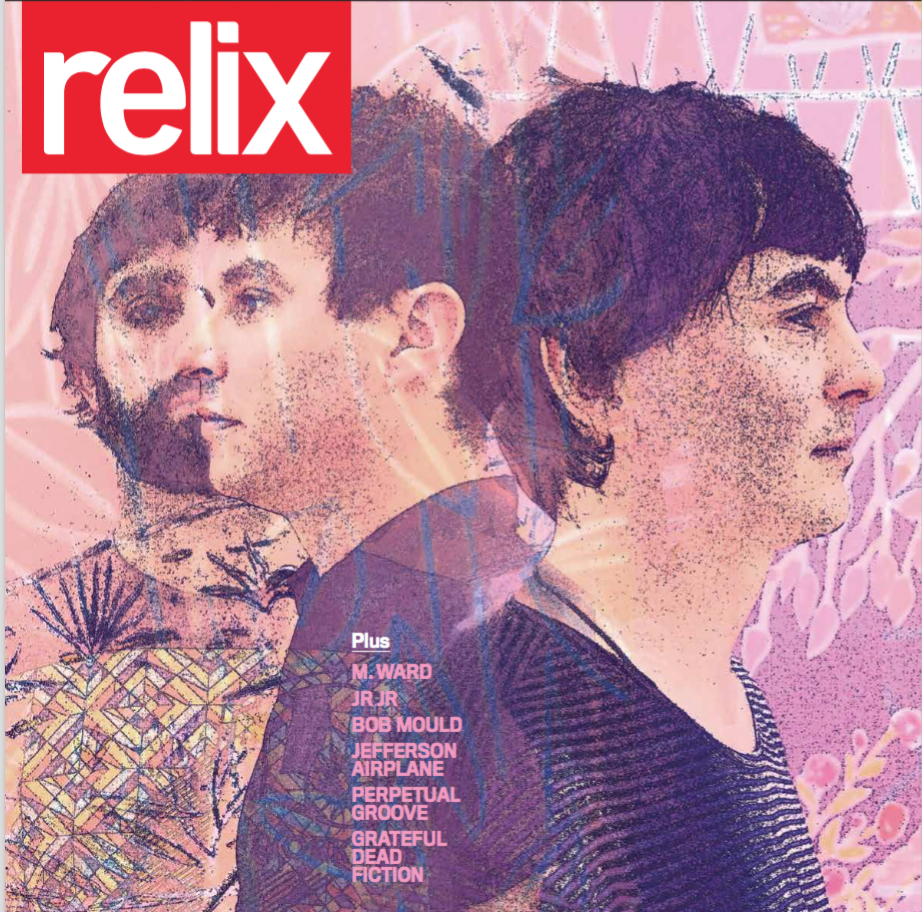

Animal Collective: Love to Say Dada

This is an extended excerpt of our March cover story. To subscribe, click here.

It’s a globally warmed December Thursday in Chelsea and delivery vans and bike messengers and chauffeur-driven SUVs and art-tourists pass at varying speeds through the foreground and background, when along comes a car—more or less at the predetermined time—and out step Animal Collective. It’s not a terribly organic entrance, but it’s the best that could be engineered. Animal Collective are the kind of band that come to New York just for a day to do press.

It’s not like I know any of the band, exactly, but it’s nice to see them anyway— familiar faces from their decade-and-a-half rise from the turn-of-the-century psychedelic-experimental corner of New York’s music grotto to the global stage. There are three Animals present today, on the sidewalk and on their newest album: Dave Portner, known on record as Avey Tare; Noah Lennox, going by Panda Bear; and Brian Weitz, who does his synth-work under the name Geologist. The Collective’s fourth, Josh Dibb (aka Deakin), is absent for this album/ tour/manifestation, but that’s the deal, and maybe he’ll be back next time, or maybe he won’t. Their management rep departs and art beckons.

The idea was to go for a gallery hop because the band’s newest and 11th dazzling, and unpredictable, album is called Painting With. While this had seemed a tad literal at first, in practice, it’s only mildly awkward, as meeting new people sometimes is, but probably no more artificial than anything else on their individual plates this week, which also include a satellite radio appearance in New York, a DJ set at Art Basel Miami, playing new music at an ambient festival in Los Angeles and whoknows-what/where-else. Animal Collective officially went international a dozen years back, when Lennox relocated to Lisbon, and while they previously lived in New York, the only place that Animal Collective were ever really from is Baltimore, where all four met growing up. A week or so earlier, over Thanksgiving, Painting With “debuted” on the Baltimore airport public address system, just because, although none of them were flying through to hear it.

Wandering through the white-walled spaces of the art gallery mini-mall in Manhattan, only Portner resembles someone who might call himself “Avey Tare,” in an eye-catching neo-futurist shirt and Steal Your Face necklace. His fellow Collectivists, on the other hand, look pretty much like the music-obsessive thirty-something young dads they are. At Garvey Simon Art Access, we awe at some of Christopher Adams’ surrealist botanical ceramics, and handmade glitch art by Karen Shaw seems to catch everyone’s attention.

In another space, while a dealer quietly shows a painting to a client, or a client’s surrogate, Lennox excitedly calls his bandmates over after he discovers a book of dada art at the gallery’s desk. Of all the 20th-century art movements, dada’s purposefully purposeless strategies are a fine match for Animal Collective, whose music obscures their harmony-laden hooks and traditional song forms in a barrage of hyper-cut electronic arrangements, falsetto leaps or other discombobulating measures. Portner recalls the time during Animal Collective’s New York days, when their music was at its scrappiest; he’d worked as an art handler, often moving work into and around Chelsea into spaces like these.

By now, though, Animal Collective have made feature-length visual albums and done cryptic installations in the Frank Lloyd Wright rotunda of the Guggenheim. Animal Collective occupy a different part of the creative economy than the overgrown college students who they sometimes resemble—more art than handler, and art in the transglobal 21st-century sense, recording for the international Domino Records and achieving festival status overseas. Animal Collective are nearly a veteran band, if they aren’t already. Like many Animal Collective projects before it, Painting With is a breakthrough, stripping out some of the more obscuring elements of their music and leaving Portner and Lennox’s singular jumping melodies and syllable-echoing arrangements on crystal-clear display, while enriching the tracks with an array of analog percussion. In the traditional narrative, 15 years in, now is about the time when the younger hungrier weirdos start yipping their way into the frame, but Animal Collective aren’t a traditional band. Like many bands of their generation, they never intended to be a band at all and have stayed as weird as they always promised they were.

Famously—or perhaps not, if you’re not an Animal Collective fan—their earliest releases didn’t bear the “Animal Collective” name at all but their individual pseudonyms. “We wanted to do it more like jazz musicians would do it,” featuring only the names of the players, says Lennox when we’re done with the gallery hop and have located the first bar that looks like it might be quiet enough to talk in.

Though, Weitz says, “working with record labels, they were, like, ‘You really need to have all your records in one section and a band name.’” But the impulse to not be a band (or not be “Animal Collective”) has never really left them. In some ways, many of Animal Collective’s projects can seemingly be traced to the impulse to express that they’re still not that kind of band.

This iteration of the not-a-band sentiment arose, Weitz says, while recording 2007’s Strawberry Jam, when Portner wanted to call the album The Painters, or perhaps change the group’s name to The Painters altogether, Sgt. Pepper’s-style. The name got nixed until—when distributing his demos for the album to his bandmates early last year—Lennox named his batch “The Painters.” Through the hermetic Animalistic process, it transformed into Painting With. Said in full extension— Painting With Animal Collective—it evokes the type of bebop albums Portner says he’s been listening to lately.

“Whenever we send each other demos, we make it under fake band names,” Weitz says, “not really for security reasons, just for fun.”

“But kind of for security reasons,” Lennox adds. All shake their heads, recalling the time their group email got hacked just before the holidays in 2008, strangers sending ghosted messages from their account to Bradford Cox of Deerhunter, among others.

It was around the same time as the hack, too, just before the release of 2009’s Merriweather Post Pavilion, that dominant songwriter Avey Tare first noticed the band’s fans starting to sing along to songs before they’d even officially released them. Weitz (his Geologist name recalling the spelunker’s lamp he wears onstage) remembers sing-alongs happening even earlier, perhaps with “Banshee Beat” from 2005’s Feels.

Probably, these are all outgrowths of the decision to solidify their name as Animal Collective, a brand that can continue pumping out material, even when the individual musicians themselves are idle. While there hasn’t been an Animal Collective album since 2012’s Centipede Hz, the quartet was hardly silent, with Lennox out recording and touring (and calling back to the bigger project) as Panda Bear with 2015’s Panda Bear Vs. the Grim Reaper and Portner doing the same with his band Avey Tare’s Slasher Flicks the year before. Portner, Weitz and Dibbs have taken to doing DJ sets under the Animal Collective banner at various locales on both coasts.

Since their loose founding a decade and a half back, there’ve now been 20 full-lengths among the four of them, including the band’s “visual album,” and the solo debut of Deakin, scheduled for release this spring, around the same time as Painting With. While known/praised/dismissed (maybe) as indie-hipster electricians or nu-EDM jammers or nonsense-chanting beat-makers, Animal Collective are rarely acknowledged for what they’ve actually done: uncovered a truly far-out kind of new psychedelia as genuinely disassociating and odd as any mythic LP that has or hasn’t been yet (re)discovered and/or reissued. And Painting With does this in whole new ways. Animal Collective are professional still-evolving psychedelic heroes for the here and now.

There are times when I wonder why Animal Collective are as popular as they are, which is in no way any kind of criticism. I love Animal Collective. Animal Collective are my kind of music: noisy and layered and cryptic and ambitious. It’s hard to understand most of the words, which come out in strangely pitched jumbles (with nice harmonies) and interrupt themselves. Avey observes that a lot of their favorite bands, like Pavement, were hard to understand, too.

And while none of their albums have cracked the Top 10 quite yet, or even gone gold, Animal Collective have one of those fanbases that dresses up for shows and smokes a lot of pot and trades live recordings and requires record company publicity departments to send out strictly watermarked file-streams. Non-fans write blog/Twitter/Bing/new-media-du-jour rants about why the band is popular, why they suck, why they represent fill-in-the-blank about hipsters/hippies/yuppies/yupsters. The not-as-satirical-as-you’d-think Hipster Runoff blogger known as Carles once built a whole vocabulary around AnCo. Editors put them on covers of magazines and at the top of websites. Staking a unique turf somewhere between avant-pranksters and indie-pop heroes, Animal Collective have constructed themselves a musical world, even if not everybody is so sure what to make of it.

In the spring of 2010, I went to the Guggenheim in New York to see the band “perform” Transverse Temporal Gyrus, which turned the inside of the museum’s rotunda into a tapestry for collaborator Danny Perez’s projections, while a new multi-channel generative sound installation rang through the space, creating a continuously new piece of music. Just off the center of the iconic rotunda, three figures stood on pedestals in giant bunny-overlord masks and stared unswervingly at the crowd. Some audience members were more bewildered than others. One group of fans (in face paint and headbands) bowed down in front of the bunny-overlords. At one point in the night, a woman next to me stood in front of one of the figures and announced very loudly, “I’ll give you a blow job if you just play a fucking song.” There were no songs played.

The bunny-overlord in question turned out to be Deakin. “I’ve often wondered if Josh was making that up,” says Weitz. It wasn’t one of the band’s more well-received affairs, nor was ODDSAC, the 53-minute “video album,” also released in 2010, that featured an entirely original score but also all four Animals acting in bizarre sketches. It had begun when somebody asked them to make a tour DVD. While the installations at the Guggenheim certainly could have been more immersive and should have been much, much louder (and is more captivating on its 2012 12-inch release), the weirdness and psychedelic discomfort were palpable.

“My aunt saw a review and got the gist that we’d done something possibly unpopular and sent my wife this note that said it sounded ‘fearless.’ It’s a weird compliment,” says Weitz. “I don’t know if I’ve ever gotten a compliment like that before for doing something that you cared about and really made some people pissed off and unhappy with you. Even though we had no intention of upsetting anybody by doing it, we were thinking about doing it for people like us.” He fondly remembers an afternoon at the Whitney in the group’s early days, when he and his non-bandmates came across a mind-blowing installation by the video artist Bill Viola without knowing quite what they were getting into.

But all of that’s OK because, then, there are times when Animal Collective do things that remind everybody why it’s blindingly obvious that they’re as popular as they are, like the music on Painting With, which almost certainly heralds the beginning of a new period for the band.

To continue reading the rest of the cover story, pick up the March issue of Relix which also features stories on Bob Mould, Perpetual Groove, M.Ward, JR JR and more.