Duane Allman: A Matter of Influence (Throwback Thursday)

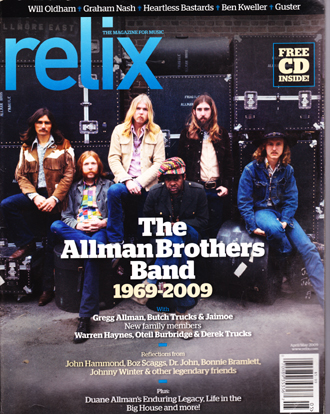

Duane Allman was born in Nashville, TN on November 20, 1946. To mark his 68th birthday, we offer this archival piece which originally ran in the April_May 2009 issue of Relix.

Electric guitarists defined the rock era. A handful of players with signatures as recognizable as the great poets of history created a landscape that we still enjoy long after they’re gone. There will never be another Duane Allman, just as there will never be another Jimi Hendrix or Jerry Garcia, but generations of unborn players will continue to explore the new vistas that these visionaries charted.

Like Hendrix, Allman’s impact is particularly remarkable in that his achievements were accomplished in only a few years. Considering that The Allman Brothers Band is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, it’s amazing to think that Duane’s defining contributions to the band’s profile took place over the course of just two studio albums, part of a third and a live recording. Nevertheless the band’s signature, multi-show stand at New York’s Beacon Theater in March is an open tribute to Duane’s influence, not just on the Allman Brothers sound itself, but on American music in general.

“We’re making the whole Beacon run a tribute to Duane,” says Warren Haynes, who took over Duane’s role in the band 20 years ago, “and bringing in as many people who were connected with him as possible. His presence is felt quite a lot in the overall spirit of what we’re doing these days. We’re trying to really honor that and trying to even second-guess what his vision would have been and try to imagine where it would have gone.” How does someone who made such a brief appearance on the public stage manage to have such a lasting impact?

The first time you hear him play, Duane Allman alters your perception of how the electric guitar is capable of sounding. Duane’s sound marries seemingly contradictory elements, at once elegant and raw, balanced perilously on the scales of rhythmic and melodic demand. His single-note guitar lines are magnificently phrased constructions played with an arresting vibrato tone, a delicate floral interlace with the resilience of tree bark. His rhythm work is always perfectly suited to the needs of the composition, played with the precision of blues and R&B masters yet fierce in service of the flow and every bit as aggressive as his lead work. Duane’s playing lends urgency to its context, even at moments of reflection.

But Duane’s signature is his slide guitar playing, a chimerical Excalibur of a sound many would imitate but none could wield as he could. Duane’s slide playing sounds like the cry of a human voice, like the clarion call of church bells, like birdsong on a spring morning. Most importantly, Duane never stopped trying to grow as a musician, exploring a connection between blues, rock, country and jazz that is still being plumbed today.

His spirit guides the Allman Brothers every night.

“It was his band and in a very real way it still is his band,” says Derek Trucks, the gifted young guitarist who is celebrating his tenth year with the ABB. “With the guys that knew him who are still in the band you can see Duane’s presence and shadow moving at times. They’re very conscious of his original intention. It still guides the band in a way. He was such a powerful musical persona, such a powerful personality. Some of the ground rules he laid down 40 years ago are still driving the ship. That’s a serious presence.”

Duane was born in 1946, a year before his brother Gregg, in Nashville, Tennessee. The boys’ widowed mother moved the family to Florida but Gregg and Duane visited their grandmother back in Tennessee during the summer. Their obsession with music dates back to one of those visits, a story that resonates because it connects them to the kind of epiphany that every music lover experiences. Gregg and Duane went to a concert in Nashville by Jackie Wilson and B.B. King that inspired them to form a band. Back in Florida, the brothers began to play together in various groups. Though they both started out on guitar, Duane advanced quickly as a player. It didn’t take long for other musicians to start noticing him.

“I was playing in Pensacola on the beach with a band called The Five Minutes,” says drummer and later producer Johnny Sandlin. “One night the Allmans played there. We played inside in the bar and they played outside on the patio, which was for the younger kids. We went to see them on our breaks and they just blew us away. Duane was the best guitar player I’d ever heard. He was the greatest even before he started playing slide. He’d play one of those Yardbirds songs and it was just amazing the way he could manipulate the volume control on the guitar. He could play where it sounded like backwards guitar.” The brothers joined up with Sandlin’s band, eventually moving out to St. Louis and working under different names. “We had a pretty decent band with The Five Minutes and when we hooked up with Duane we felt that nobody could stop us,” says Sandlin, “and Gregg was such a good singer.” In St. Louis the band built a following and became managed by Bill McEuen of The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. McEuen brought the group out to Los Angeles, where they recorded two albums under the name Hour Glass. The experience was bitter. “We were used to playing four nights a week and we never thought about image or anything,” says Sandlin. “When we got out to L.A. it was like everything was turned upside down, it was more about your image than your musical ability. We were signed to Liberty and they wanted us to make hit singles and be like Gary Puckett and the Union Gap.” The only positive to come out of the L.A. experience was that Duane started to play slide guitar. “Duane was sick and he was taking some Coricidin and he used the empty bottle for a slide,” says Sandlin. “He had heard Taj Mahal’s The Natch’l Blues, at that point Jesse Ed Davis was playing slide with Taj. Duane really took to it and started learning to play it. He started playing it on three or four songs during our sets. He was a little rough at first. But ‘Statesboro Blues’ was on that record and I guess that’s the arrangement Duane took it from. It took him a while to get the intonation down but by the third or fourth gig he really had it. It made it all the more frustrating that we weren’t able to play live.”

The band went to Rick Hall’s Fame Studios in Alabama and cut some demos that they felt represented their sound, including the very good “B.B. King Medley,” but Liberty rejected the tapes. “They said, ‘We hate it, we don’t put out stuff like this,’” Sandlin recalls. “We put our heart and soul into it and everybody loved it, it still sounds good to me to this day. But they didn’t like it, so that was really the end of the band.”

Rick Hall liked Duane’s playing so much, though, that he asked him to join the session team at Fame [see article on Fame pg.37]. House guitarist Jimmy Johnson already knew Duane from producing the Hour Glass demos.

“He could play rhythm, acoustic, anything you want,” says Johnson. “He couldn’t read a chart but he had this amazing talent. You hear this all the time but Duane really had it. He’d hear a song one time and you didn’t have to tell him – you play any chord in the song and he would know right where it was. “We would always talk about guitars. He played a Stratocaster and a Gibson Les Paul. He always used a Fuzz Face. That was basically for distortion. He’d line up about ten of those nine-volt batteries and he figured out a way to drain the power in those batteries down to about a third. He always said that they sounded ten times better when they would almost be powered out. It gave him the more textured distortion he was looking for.” Johnson was particularly impressed with Duane’s thirst to play. “He had the guitar in his hands at least eight to ten hours a day,” Johnson recalls. “I don’t know anybody who did that. He was such a prolific player, he knew everything about his guitar, about the neck of his guitar, where to play, how to play, where the sounds were, the best place for the good sounds. People that bend strings like he did, there are pushers and pullers, and Duane pushed more than he pulled. He’d put two fingers together and get two strings and bend them up, you didn’t see him pulling them down, it was mainly pushing up. “When it came to slide, forget it,” Johnson laughs. “I think part of what made his sound on slide is how familiar he was with the instrument. He did it out of love, y’know? Sitting around the studio he always had the guitar around his neck, playing it, even when he wasn’t on a session. He made me feel bad. I was saying, ‘God, I gotta get me on the Duane Allman program.’ That’s how special he was.”

Within a year Duane made his reputation as a session star. He was on the historic Aretha Franklin Soul ‘69 sessions and even suggested material for Percy Sledge and Wilson Pickett to cover. “Duane never really liked being a studio guy, showing up at ten in the morning and playing whatever was required,” explains bassist David Hood. “But he was good at it. We played on a lot of good records together. One of the songs that was his idea to cut was the Percy Sledge version of ‘Kind Woman,’ the Buffalo Springfield song.”

Hood also recalls the legendary anecdote in which Duane convinced Wilson Pickett to record “Hey Jude.” “We had all gone to eat lunch and Duane stayed back at the studio with Wilson and convinced him to cut the song,” says Hood. “It was a really unusual thing to suggest because it was a big hit for The Beatles at the time and the idea of taking them head on was a pretty far-fetched idea but Duane thought it was a good idea.”

Though his time as a studio musician brought Duane to the attention of Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler, who signed him to a contract, his goal always remained to lead his own band. Between sessions he began work on a solo album, pieces of which have emerged over the years, but it was never completed. Instead, Wexler turned Duane’s contract over to Phil Walden, who was starting Capricorn Records and wanted to record Duane leading a trio. When Duane showed up with his band, though, it was a sextet – he and his brother with bassist Berry Oakley and guitarist Dickey Betts from the Jacksonville band The Second Coming and two drummers, Jai Johanny Johanson and Butch Trucks.

“Duane called me to come hear the band in Daytona,” recalls Sandlin, who became Capricorn’s house producer. “It was one of the earliest gigs and may have been a glorified rehearsal. It was wonderful. You could sense that this was the beginning of something.”

In September 1969 The Allman Brothers Band recorded its first album that included the classic songs “Dreams” and “Whipping Post,” but the band’s reputation was made onstage, especially during the free Sunday concerts at Atlanta’s Piedmont Park that inspired a generation of musicians to play the loose-limbed improvisational music that became known as Southern Rock and lives on today in the jamband aesthetic.

The style combined the energy and dynamics of blues-based guitar rock with the modal improvisations introduced by jazz visionaries Miles Davis and John Coltrane. The Allman Brothers didn’t really catch on at radio even after making an outstanding album in 1970, Idlewild South, but Duane became a household name after joining with Eric Clapton to make what may be the greatest rock record ever, Layla and Other Assorted Rock Songs.

Producer Tom Dowd decided to make the next Allman’s release a live album, recording on March 12 and 13, 1971 for what became The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East. It was a breakthrough recording that sealed the group’s reputation. Promoter Bill Graham chose them to headline the final show at the Fillmore East that July. Three months later Duane was gone, killed in a motorcycle accident on October 29.

When an artist dies at such a creative peak there is always an open question about what they would have achieved had they lived. Those who knew Duane felt he was on the verge of even bigger things. Tom Dowd, a veteran jazz engineer and producer, called Fillmore East “the greatest fusion album I’ve ever heard.” Sandlin agrees. “They talk about Southern Rock,” he says, “but Duane was heading toward jazz. He was listening to Miles and Coltrane. He loved Coltrane. Duane was working on an arrangement of ‘My Favorite Things.’”

Warren Haynes has followed through on Duane’s interest in combining rock and jazz elements through Allman Brothers compositions like “Kind of Bird” and in Coltrane-inspired jams with his own group, Gov’t Mule. He recently marveled at the fact that the ABB is celebrating its 40th anniversary the same year Davis’ Kind of Blue turns 50.

“Now it makes sense,” he says. “At the time they seemed further apart. It’s interesting when you think about Duane’s roots in blues and R&B. As he was growing as a musician, jazz musicians were becoming much more important to him. He talked a lot about how important Coltrane was in influencing him. It’s almost a cliché to say that you’ve been influenced by John Coltrane these days because it’s so obvious that he’s an icon. But for somebody in the early ‘70s to actually take that influence into a rock or pop sensibility was quite a stretch. Perhaps Duane helped to make Coltrane a universal influence in ways he didn’t even realize, the same way that people like Duane and Clapton contributed to the rediscovery of Robert Johnson.”

Bonnie Bramlett and her daughter Becca will be among the many guests to join the Brothers during the Beacon run, remembering not just Duane but Delaney Bramlett, who died last December. Duane played on the Delaney and Bonnie album Motel Shot, and Delaney played “Come On In My Kitchen” at Duane’s funeral.

“We knew each other from back in the day, even before the Allman Brothers, when Johnny Sandlin was the drummer,” says Bonnie. “Oh, Delaney and Duane just hit it sooo off. They were like brothers.”

In Bonnie’s ruminations about the days when “we were all not famous together” she pointed out a different kind of influence that Duane was part of.

“Back then there weren’t many white people doing the black expression,” she says. “We just did what we liked. We liked to play the blues. We were aware that we were crossing color lines, not only with black musicians being played on white stations but with white musicians being played on black stations. There was never a picture of Booker T and the MGs on their album cover. Delaney and Bonnie got signed to Stax and they thought we were black. And Duane was a big part of this because he played on all the Atlantic stuff with Aretha and Wilson Pickett and other R&B singers.”

Bonnie’s observation was particularly poignant because just as we were talking, Barack Obama was in the midst of crossing the ultimate color line by taking the oath of office as President of the United States.

“The color lines were being destroyed by the Muscle Shoals guys and the Memphis guys,” she concludes. “It was a sign of the times when we went from just doing what we wanted to do to becoming successful by doing it.”