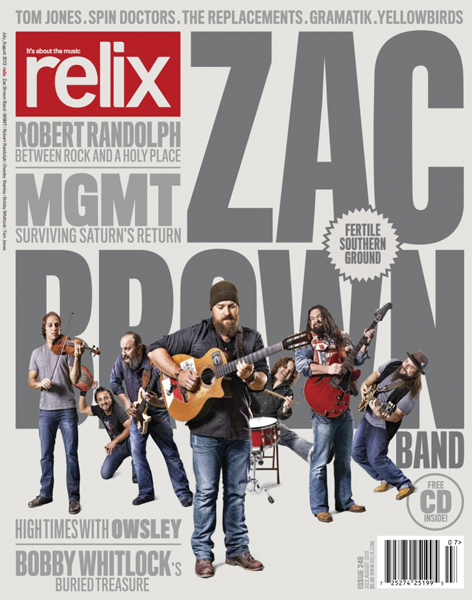

Zac Brown Band: Everywhere Is Southern Ground

Following recent reports that Dave Grohl will produce the next Zac Brown Band album, with Oteil Burbridge drawn into the fold as well, today we’re sharing our July-August cover story on the ZBB.

As the mid-May sun prepares to dip beneath the horizon and bathe Red Rocks Amphitheatre in striking dusk hues, it’s Avengers Assemble time on Zac Brown’s tour bus. With just more than an hour left until they hit the stage, the members of the Zac Brown Band have arrived for what their daily itinerary identifies as “vocal warm-ups.”

Despite the formal description, the group does not implement a regimented approach to their singing prep, which is more in line with a friendly yet focused campfire pick. Three acoustic guitars, a mini electric bass and some ambulatory drum sticks are put to good use as the group begins working up “Day of the Dead,” a new song slated to make its live debut later that evening.

Although the vibe is loose and informal, this is a sacred time for the group—something of a pre-game locker room ritual. It’s not that the musicians don’t see each other. Ninety minutes earlier, they stood in formation to greet 150 Zamily fan club members individually and then, assumed their positions behind a phalanx of chafing dishes to serve dinner at the band’s nightly Eat and Greet. However, beyond honing their vocal harmonies, the musicians carve this time out to ensure that they can connect and exchange ideas about the upcoming show without any of the distractions that can come from headlining three sold-out nights at one of America’s most beloved and prestigious amphitheaters. (Although, on rare occasion, they make exceptions, such as the recent evening in Australia when Brown looked up to see Bruce Springsteen smiling at him.)

Rather than situate such warm-ups in a sterile, generic dressing room (even if the Red Rocks band room is atypical, with an enormous sandstone boulder commanding attention in the corner), the group opts for the familiarity of Brown’s bus. Here, their de facto eighth member, songwriting partner Wyatt Durrette, joins them as well as Cyra, Brown’s Belgian Shepherd, who wanders through the cabin as a good-natured, silent presence. Brown’s bus serves as their regular pre-show clubhouse and it also supplies a comfortable slice of Southern Ground.

Fiddler Jimmy De Martini pulls up a demo of the song on his phone and they listen to a few bars before making a go of it themselves. For a tune that they haven’t performed in a few months, they summon the melody rather swiftly, reflecting a collective skill set that is a point of pride for the group. There is some affable discussion of the interlaced harmonies toward the close of the song and after running through it four times, they reach their comfort level.

“Day of the Dead” will appear next in a different context at the night’s end when it opens the group’s four-song encore. The Zac Brown Band will juxtapose it with a cover of Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb,” while donning matching full-body skeleton costumes and masks that emit an eerie phosphorescent glow under the black lights projected onto the group. (It’s safe to say that no one has ever written the preceding sentence about any other band honored by the Country Music Association, Country Music Television and the Grammys.)

As warm-ups proceed, Brown suggests they revisit “Let It Go,” the lead track on the group’s 2010 album You Get What You Give, which they have performed on only one other occasion since late 2011. The group made an effort to dig deep with the Red Rocks setlists, working from an Excel document produced by tour manager Paul Chanon, followed by an hour of full-band discussion. Even so, at the previous day’s Eat and Greet, a fan asked Brown whether the group would be performing “Day That I Die” from their latest record, Uncaged. Brown realized that the song wasn’t slated to appear and later called an audible, dropping it into the setlist and acknowledging the Zamily member from the stage.

“Let It Go” is a sprightly, lighthearted composition. In the second verse, Brown shares a homily in his affable tenor:

You only get one chance in life to leave your mark upon it/ And when a pony he comes riding by you better set your sweet ass on it

The journey of Zac Brown’s posterior to Red Rocks is the product of conviction and collaboration, as well as a commitment to a burgeoning empire of businesses under the Southern Ground umbrella, devoted not only to music but also to catering, producing knives, manufacturing leather goods and Brown’s “highest mission,” assisting special needs children at Camp Southern Ground.

Zac Brown has never lacked forconfidence. He remembers witha laugh that his mainstreamacceptance came about adecade too late. “As soon as wemade our first CD in early ‘98,we were going on the road in avan with my Jack Russell andmy drummer, a PA and a bunchof our CDs,” he says. “We weregoing to be big within a yearand I wouldn’t have it anyother way. Ten years later, westarted getting traction.”

Raised in the North Georgia Appalachian Mountain towns of Dahlonega and Cumming, Brown was born in 1978 as the 11th of 12 children with 21 years between him and his eldest sibling. In this setting, complicated by his parents’ eventual divorce, Brown developed an independence in tandem with his passion for music.

“I was the guy who had his guitar every day,” he says. “I carried it to school, I carried it to football practice and before, after, during the crack of every day, I was playing my guitar. It was always company to me. But all of it really started with me being a music fan. I remember I got my CD player right when they came out and I had Garth Brooks’ first CD, the Eagles’ Greatest Hits and Fleetwood Mac’s Greatest Hits. I wore them out. I could sing every song. Later on, I got into Al Green, Marvin Gaye, The Beatles, Pink Floyd, the Allman Brothers and Bob Marley. Then, it was the heavy singer/ songwriters: Jim Croce, Dan Fogelberg, Gordon Lightfoot and Cat Stevens. I loved all of it.”

Brown began performing as a solo act while still in his teens and continued to gig at the University of West Georgia While still in college he experienced an initial milestone in securing a residency at a Panama City, Fla. bar.

“We played 10 nights in a row for $150 a night, six hours a night,” Brown recalls. “I remember thinking, ‘We made it.’ It was me and a drummer. Our band name was Far from Einstyne and we eventually toured six years like that. I had to hire a guy to drive us because we had three nights in Panama City, two nights in Atlanta, two nights in Birmingham—all summer—so there was never a

night off. I couldn’t talk most mornings. I’d wake up and I’d chug water all day, and by the time night came, I could sing again.”

As Far from Einstyne made the rounds on the Southern circuit, talent scouts who took interest in Brown’s music occasionally contacted him, with some qualifications.

“I turned down record deals along the way because the people that would approach me were like, ‘What do you want out of a record label, son?’ This guy calling me son—he’s probably eight years older than me. Then, he’d say, ‘We’ll get you some boots and a cowboy hat.’ That’s when I’d say, ‘Check please.’

“This is my path, I enjoy the freedom to just be myself,” Brown observes, while seated on a couch in his tour bus, two hours before warm-ups, gently comforting his dog who has curled up next to him. “That’s why I wear the hat that I want to wear and I dress the way that I want to be and it’s not because of anybody else’s expectations. It’s [through] my journey as a human being [that] I’ve come around to being comfortable with who I am. Everybody’s always changing and I’m not defined, but I’m comfortable being myself and that was strange for some people at first. They were like, ‘Why do you wear that beanie?’ And I was like, ‘Because that’s what I want to wear.’”

The singer pauses and then his tone changes ever-so-slightly. While he maintains his equanimity, his voice is slightly pinched as he reflects, “It’s always an interesting thing for me. Some people can come up and say something rude to you—they’re dressed up in a polo shirt and khaki pants and are like, ‘Why do you have a beard on your face?’ Now, I know how to dress like that guy, I know how to be that guy—well not be him, but I know how to fit into every part of that culture and be a chameleon and do that. But who wants to be like everyone else? It is always those people that are very traditionally presented who will come up and say those things. How can you even say that to another human being?”

Brown stood firm, taking a somewhat fatalist approach to his career, confident that if he pursued his own path and his own muse, then audience acceptance would follow. The first decade of the 21st century proved such faith to be justified.

“I feel like my life unfolds before me and it’s my responsibility to follow it however weird that it may go,” he philosophizes. “I felt confident in the path that I’ve been on. I don’t know how to fully explain that and I don’t understand it myself, but there have been times and places that I was supposed to meet certain people.”

One of those people was Wyatt Durrette. The two connected when Durrette was managing the Dixie Tavern in Marietta, Ga. Durrette recalls, “I booked him [to play] on a barstool in front of like four people on a Tuesday night. When he played, you could automatically tell there was something special about the guy. The second time he played, I got up and sang with him and was like, ‘Hey, I write music. Why don’t we get together and write?’ So the following Sunday, we wrote four songs in one night. Then, we became good friends and started writing all the time. It went from four people to 500 on a Friday night.”

One of these collaborations was “Chicken Fried,” which would become the Zac Brown Band’s breakout No. 1 country single in 2008. Another early effort was “Whatever It Is,” the song that would follow “Chicken Fried” up the charts before landing in the second slot. Both songs were originally recorded for the Zac Brown Band’s 2005 independent release Home Grown.

What is remarkable about their partnership—in particular, Brown’s immediate belief in his co-author—is that Durrette is not a traditional songwriter. In fact, he can neither read music nor play an instrument.

“I’ve taught him the G chord for 12 years and he still doesn’t know how to play one,” Brown offers with a grin. “But he can hum a melody and some lyrics and he’s really good at it. It was just one of those things: The first time we sat down to do it, he taught me little pieces of stuff and I could hear what the rest of it was supposed to be. I could hear the chords and the music behind it.

“We nicknamed him ‘Wrecking Ball’ because he’s very blessed but he’s learned everything the hard way,” Brown continues. “He has a temper although he’s gotten better over the years. He had testicular cancer and he had to have one of his boys removed and that’s also one of the reasons we call him Wrecking Ball. He’s like my brother. When he was managing the Dixie Tavern, we got in a lot of fights together because I had to fight the guy who was with the guy he was fighting. But we always won, knock on wood.”

Durrette shares the origins of “Highway 20 Ride,” which presents the story of a divorced father returning home after spending time with his child. “When I used to pick my son up, I’d have to drive to Augusta, Georgia, and pick him up and drop him off there, and then, do the drive back alone,” he recalls. “I wrote a lot of that song in tears, on that road. And Zac’s father got him every other weekend [after his parents divorced]. So when Zac helped me write it, he was writing from the kid’s point of view seeing his father every other weekend and I was writing from the father’s point of view seeing his kid every other weekend.”

One aspect of songwriting that the pair have never concerned themselves with is musical genre. Brown explains of Durrette: “He is a professional drinker, vacationer and a very talented wordsmith who loves to be on the beach on his belly— that’s where he’s happiest. Our love for Bob Marley and Jimmy Buffett definitely comes through. I enjoy the freedom when we write a song to say this style of music best accompanies these lyrics, whether it’s based in reggae or bluegrass or rock or country. Life is diverse and I love all different kinds of music. A lot of what moves me is lyrically based but when you get the marriage of good music and lyrics, I don’t want anyone to tell me how I want to express it.”

Now that Brown had the songs, he needed the band.Durrette had a hand in this aswell. In late 2004, he introducedBrown to Jimmy De Martini.A classically trained violinist,De Martini was a foundingmember of a group renownedfor its truth-in-advertisingmoniker: the Dave MatthewsCover Band. (The groupreceived a nod in an episode ofthe adult cartoon Aqua TeenHunger Force when a spaceshipof visiting “frat aliens”displayed a bumper sticker thatread “Dave Matthews CoverBand Cover Band.”)

Bassist John Driskell Hopkins, a rock singer and songwriter in his own right, who had worked in the studio with Brown and initially intended only to fill in temporarily as a favor, soon joined De Martini. The three anchored the version of the Zac Brown Band that preceded the release of 2008’s The Foundation, with other musicians sliding in and out of the group.

Of the shifting roster, Durrette opines: “Zac is a super-positive human being and does not tolerate negativity. The name of the [2010] album, You Get What You Give, is tattooed on his arm. A lot of it was just negativity offstage. He was like, ‘We can’t have it. It’ll bleed through in the music. People will notice it.’ There were a lot of great players but a lot of the time, that’s what it had to do with.”

The five-piece version of the Zac Brown Band whose photo appears on The Foundation (even if the two newest members did not contribute to the recording) included drummer Chris Fryar and organist/guitar player Coy Bowles.

Fryar is a jazz-influenced player who previously appeared with Allman Brothers Band bass player Oteil Burbridge in Oteil & The Peacemakers. (Fryar, whose nickname is “Sweets,” due to his fondness for confections, shares a Peacemakers tattoo with Burbridge and hopes that the bassist will revive the project, if only for an occasional gig.)

Bowles first met Brown when they were undergrads at the University of West Georgia and, eventually, fronted his own blues-based ensemble, Coy Bowles & The Fellowship. An offer to open a run of shows for the ZBB soon transformed into an invitation to join the group.

The Zac Brown Band’s portraits on their next two albums further document growth. You Get What You Give presents a six-piece with Clay Cook on electric lead guitar. Cook and fellow Berklee College of Music student John Mayer left school in 1998 and relocated to Atlanta, where they performed as the Lo-Fi Masters for a few years. (Cook received songwriting credits on Mayer’s first two albums for numerous tunes, including “Neon,” which the ZBB now performs and which Mayer has guested on.) His uncle also happens to be Marshall Tucker Band cofounder and lead vocalist Doug Gray, and the guitarist toured with that group before Brown enticed him to join the band.

Most recently, as reflected on 2012’s Uncaged, the Zac Brown Band has become a septet with the addition of Cuban percussionist Danny de los Reyes, whose family line of percussionists includes his grandfather, father and brother Walfredo (a former member of Santana’s band and the subject of a Phish song that takes his name). De los Reyes’ second-ever gig with the group was at Red Rocks in 2011, a venue that he previously performed at with Earth, Wind & Fire, Yanni and Don Henley.

Brown explains, “The [Allman] Brothers always had a percussionist, Widespread Panic has a percussionist—a lot of bands that I really love. I’ve also heard a lot of bad ones and that can make a lot of flamey crap in a band. But Danny’s one of the best A-list percussionists, period, and we just hit it off.”

Although the Zac Brown Band first received national airplay on country radio, the full sweep of their music defies easy categorization. De Martini remembers, “When ‘Chicken Fried’ came out, a lot of people came to see us play and that’s all they knew. But we had been touring for a while playing all sorts of original songs and not just country-style songs. So there was a conscious decision that we were going to jam and play longer shows and not just do our radio hits because then, we’d get stuck doing that for the rest of our lives because our fans would expect that from us. You mold your fans and they mold you. So we set up our show that way and, as our crowd grew with us, they’ve come to expect it.”

This process has yielded a motley collection of covers. The Red Rocks run included takes on Nirvana (“All Apologies”), Led Zeppelin (“Kashmir”), Tom Petty (“You Don’t Know How It Feels”), Metallica (“Enter Sandman”), James Taylor (“The Frozen Man”), Dave Matthews Band (“Ants Marching” with some of Edgar Winter’s “Frankenstein” thrown in for good measure) and The Marshall Tucker Band (an apropos rendition of “Can’t You See”).

ZBB did not perform their version of Rage Against The Machine’s “Killing in the Name,” although it surfaces on occasion as well. (This included a memorable soundcheck at a Christian school, where the group, unaware of the setting, serenaded the student staffers with a barrage of “Fuck Yous.”)

The group has also veered away from the lighting and production elements associated with traditional country shows. De Martini cites the group’s 2011 summer European tour opening for Kings of Leon as influential. He and his bandmates marveled that the Kings took the stage accompanied by red smoke without direct lights on the musicians, an approach that is anathema in country circles where “you always see the lead singer in spotlight and everybody else in black and the video is just the star’s face the whole time.” In response, after the ZBB returned home, they altered some elements of their live presentation.

As for the band’s ongoing musical development, Hopkins mentions that, increasingly, observers are placing the band “in the jam category, which I’m excited about because now we’re not seen to be based in just one style. I think that gives us a lot more leeway to do things musically.”

“In some ways, that’s a big part of who we are,” Fryar adds. “We allow ourselves those moments in every show to stretch and have some fun, take musical journeys. It’s opened us up to other listeners.”

There is no question that the group boasts many hallmarks of a jamband, if one considers the sheer variety of the music, the chops of the players and the open-minded, collective spirit of the ensemble. Indeed, even as Bowles affirms that the band’s goal is “to honor the songs above and beyond everything else,” he also interjects that live versions of their original “Who Knows” can sometimes stretch to nearly 15 minutes in length.

Zac Brown Band has covered Widespread Panic, invited Warren Haynes and Gregg Allman to the stage and, at September’s Interlocken Music Festival, Brown will perform a special set with The String Cheese Incident.

One individual attending his first-ever ZBB show during the final night at Red Rocks was SCI bass player Keith Moseley, who was on-hand to meet Brown and get a taste for their forthcoming collaboration.

A few days later, Moseley reveals that they have since been in steady communication via email and hints of new arrangements and interpretations that they’ve already contemplated for the festival, noting, “Zac has an incredible music vocabulary and library. He reminds me a lot of Keller [Williams]. They’re very different in that Keller’s quirky and into the looping thing—but just in terms of being a pure singer/songwriter with a huge catalog of tunes and being driven.” As for the Zac Brown Band, Moseley suggests that a comparison with his own group isn’t far off base. “They’ve got the same set-up as we do: bass, drums, percussion, keys, violin, acoustic guitar and electric guitar,” he says. “It’s pretty identical. They also go from calypso to bluegrass to rock and, on that night [when I saw them], they covered everything from Nirvana to Pink Floyd. So there’s really not that much of a stretch between us in some ways. Obviously, they’re more deeply rooted in the country vein and what impressed me were their vocals. Those guys can sing their asses off.”

Such approbation helps explain how the Zac Brown Band was able to sell out three nights at Red Rocks (on a run of dates that started on a Wednesday, rather than over a weekend). Only two other acts will attempt at least as many shows at the facility during the summer of 2013: Widespread Panic and Furthur.

Midway through the third performance at Red Rocks,Brown pauses to make a sincere,almost solemn appeal. As themusic comes to a halt, heencourages the audience tosupport his “higher purpose.”The ambition he shares doesnot reflect an artistic goal orpromote a religious calling(even if Brown’s parlance andpassion may echo the latter).Instead, he shares hisaspiration to build a summercamp to assist children withdevelopmental disorders. Herethe musician isn’t a figureheadtapped solely to raise fundsfor others. Rather, he hasspearheaded Camp SouthernGround as the charitable coreof his own ambitious businessconglomerate.

Brown’s passion before 10,000 fans echoes the enthusiasm that he exudes in a one-on-one setting hours earlier on his tour bus. Here, Brown acknowledges that in developing both the camp and the Southern Ground brand as a whole, he is emulating the process by which he shaped his musical group.

“I like to build things, I like to empower people and I like to harbor talent,” he remarks. “When I find people who are really gifted, I like to give them a job to help us grow a company. I’ve got 136 employees, and most of them, I’ve handpicked. It’s backward from a normal corporate job where you have a job position and a job description and you find someone to come in and do that. I find people that are talented and figure out how we can work together.”

One of these people is chef Rusty Hamlin. The two met more than a decade ago when Wyatt Durrette took on a second job as head bartender at Hamlin’s Atkins Park restaurant in Smyrna, Ga. He invited Hamlin to join him at the Dixie Tavern after work, saying, “My buddy is playing music up there. I would love for you to listen and meet him. He’s amazing.” The chef not only connected with the music but also the musician, as he and Brown shared a passion for food (In 2004, Brown and his father opened Zac’s Place, a restaurant on the shores of Lake Oconee, Ga. where Brown both cooked and performed until he closed the spot a couple years later

after land developers swept through the area.) Hamlin often visited Brown at home during this period, occasionally discussing fan hospitality and the ways to break down the barriers between the audience and performer. This is where they fashioned the idea for the Eat and Greet, although it would be years before they realized the concept, at which point Brown pulled Hamlin aside one night at Atkins Park and told him to be ready for the road in seven days.

Hamlin and one of his employees, Josh Prichard, found an old taco trailer that they christened “Miss Treated” and hit the road with the ZBB in 2008. It was trial by fire at first, but Hamlin now oversees “Cookie,” a custom-built mobile professional kitchen that fills a 54-foot-trailer. There, he prepares fresh dinners each day while the band is on tour: grilled pork and beef tenderloin with Brown’s signature Love Sauce and Georgia Clay Rub, and pocket-knife coleslaw from Brown’s recipe, along with multiple sides that Hamlin creates from whatever he finds at local farmer’s markets. In Colorado, this included a chard and mushroom salad, roasted fingerling potatoes with caramelized sweet onions, balsamic and bacon fiddlehead ferns with strawberries and goat cheese, pumpernickel croutons and a tomato balsamic jam. Before one of the meals at Red Rocks, Brown informs all of the fans in attendance that “eating and breathing on each other tears the walls down.”

This same spirit that guides Baby Goo Hospitality—the formal entity that operates the Eat and Greets—also animates the group’s Southern Ground Music Festival, which will return to Nashville, Tenn., and Charleston, S.C., in 2013.

Meanwhile, such enterprises as the Lucy Justice merch company, the Southern Ground Artists label and Southern Reel, which shoots videos for the stable of artists, all seem tied into Brown’s core operations. So does the Nashville studio he’s acquired, where the band plans to record their next album over the coming winter.

Southern Grind (knives) and Southern Hide (leather goods) might seem odd additions to his business portfolio but as Brown explains, matter-of-factly, “I’ve got a big passion for knives. We make really nice all-American knives and, when I first thought of the leather company, it was to make sheaths for the knives.” To promote synergy, Brown has located all of these businesses in the same facility. “We just bought a building and built it out. We have 150,000 square feet now. That’s a once-in-a-lifetime build. It’s like when Coran Capshaw did Musictoday and he bought that old ice cream factory and turned it into this ginormous distribution and fulfillment company.”

It’s one thing for an artist manager and entrepreneur like Red Light founder Coran Capshaw to take such initiative but for an active, working musician to do the same is unprecedented.

Yet this is only part of the story, as many of these businesses will support his passion project, Camp Southern Ground. A product of Brown’s experiences as a camper and later as a counselor, the goal is to create a facility that will “allow children to overcome academic, social and emotional difficulties so they may reach their full potential by providing them with the opportunity and tools necessary to achieve excellence in all facets of their lives.”

Brown envisions that it will be “a big hub for treatment for kids with developmental disorders. We’re going to build a campus that’s going to be state-of-the-art and the air quality will be great. But we’re also going to empower thought leaders, who are on the brink of discovering new approaches to help these kids. Then, you can take the curriculum created by all these brilliant people and put it into a school system and a special ed. program to make kids better—the greater vision for it.”

It’s a great vision indeed, and one that is becoming increasingly tangible. Brown also has made it a collective one. At Red Rocks, the musician stops to describe what the camp means to him and a message appears on the facility’s video screens informing concertgoers how to text a donation. For Zac Brown, everything is entwined in his fertile Southern Ground.

“We’re going to take the high road and the long road and wrestle it down to the ground,” Brown explains of his prospects for success, moments before stepping off the bus for the evening’s Eat and Greet. “Everything I’ve ever done has been trial and error and finding the right people and making it better over time. I’ve tried to make the right decisions and treat people the right way, and hopefully, the karma will help carry me through. I wanted to put together a legitimate band and find players who could come together and all lay our egos down to let the music be first. I’m proud of my band, proud of the guys I work with. It’s a weird collection of dudes. But it works, you know?”