The Deadologists

They descend on Albuquerque like the Deadheads that they are, but their destination involves neither concerts by members of the Grateful Dead, nor any other band. This particular seasonal migration of Dead freakdom has been going on for 20 years now, unfailingly, each February. Those arriving the night before meet up to exchange secret Deadhead handshakes, but mostly they’ll start to gather blearyeyed over the breakfast buffet or in a conference room in the morning. Somewhere around 30 or 40 of them file in, sometimes as early as 8 a.m. (on a Saturday!) for presentations, roundtables and discussions. The Grateful Dead academic caucus at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association is in session.

The opening panel this year includes a dive by Laura Meriwether into the specific Funk & Wagnalls entry from which the band drew their name and how “Grateful Dead” came to be in that dictionary in the first place, when the phrase wasn’t in the OED or elsewhere. Jan Wright describes her project to create an index for the beloved and info-packed ‘80s Deadhead zine The Golden Road. Also on the agenda for day one: the Dead and third-wave feminism (featuring Rhoney Stanley, LSD lab assistant to her partner Owsley), an update on the Israeli Deadhead scene and a half-dozen other presentations.

I have official conference business, too, but I’d be there even if I didn’t. I am there because, to twist Willy Legate’s famous saying: There is nothing like a Grateful Dead conference.

“We’re really right at the point where we’ve achieved critical mass, where there’s enough good work done in different fields to have a sense of: ‘This is really robust. This is really interesting,’” says Nicholas Meriwether, a conference attendee and organizer since its early days, a Deadhead since 1985, and historian in charge of the Grateful Dead’s official archive at UC Santa Cruz since 2010. He cites 26 different disciplines that’ve been applied to the burgeoning multidisciplinary field of Dead studies. “There’s a real rigor and ambition and excellence in the band’s craft that is really the core of why Dead studies exists,” he says, “and the fact that it happens to ripple outward in so many interesting ways and contexts makes it even more compelling.”

Like other Deadhead sub-communities, the scholars of the Albuquerque caucus take on qualities of both groups—in this case, Deadhead passion (and humor) mixed with academic methodology. In the entirety of the SWPACA conference with its hundreds of attendees, the Dead caucus is the only group that meets full-time for the entirety of the four days.

A whole academic rainbow prisms outward from the Dead’s Steal Your Face logo. There are sociologists, economists, feminists, philosophers, historians, poets, radio hosts and more. Nick Meriwether wishes there were more anthropologists. One group that seems especially poised to take flight is the musicologists, a sub-tribe studying the band’s proper text, the music itself. Their literature includes, to name one shining example, Graeme Boone’s lyrical explorations of “Dark Star” and “Bird Song,” and other topics. But perhaps at the foundation of Dead studies lies the only marginally recognized field of Deadology.

To really understand the United States, you need to understand the ‘60s, Nick Meriwether told me (approximately) when I was researching at the Grateful Dead Archive in Santa Cruz a few years back. And in order to understand the ‘60s, you have to understand San Francisco. And in order to understand San Francisco, you have to understand the Haight, and in order to understand the Haight, you have to understand the Grateful Dead.

This is the why of Dead studies and Deadology: the deep study of the Grateful Dead in order to really understand the Grateful Dead and, by extension, everything else. Not that most Deadologists would frame their own obsessions as such. Many perhaps stop after the first part, but there is the usually unspoken agreement that the Grateful Dead were, and are, one of the most remarkable phenomena of the last 100 years. “Better than Beethoven!” legendary Dead collector Dick Latvala was known to bellow. One of the first collectors, Latvala kept carefully annotated notebooks of his acquisitions with careful metadata about the recordists, tape generation, and more, in addition to his own close listening notes. But Latvala didn’t trade tapes, exactly, so much as send delicious Hawaiian weed to Dead tapers in return for reels. It worked like a charm, and frames the late great Dick into the great American narrative of the underground hip economy that welded drugs to rock and roll.

Primarily because of obsessives like Dick Latvala, Deadology is the oldest and most matured of all the subdisciplines in Dead studies. Being an imaginary field, it requires no specific academic status to enter, only that one do good work, and Deadheads have been doing good work in that regard since the the early ‘70s. The origin point and bedrock for all Deadology is (perhaps, obviously) the band’s obsessive tape collectors—two of them started this publication in 1974—who began to piece together the band’s hundreds of concert dates in search of all the reels. By the ‘80s came DeadBase, the infamous phonebook-sized framework of Dead setlists whose master chronology doubles as a meaningful history of a certain not-insignificant segment of the American population.

That’s my argument, anyway, (COMMERCIAL MESSAGE HERE) and I spend a few hundred pages explaining it in my new book, Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America, showing how the Dead’s timeline was entwined with that of LSD, technology, and other neon red, white and blue threads. And while I had a magical time this year, as always, in the heady high-altitude environs of the Albuquerque conference, the thought that kept returning to me was how the first generations of Deadologists had provided a basis for so many of the presentations.

For anyone relying on lyric transcriptions (the Stanford heads put Dead lyrics on the national ARPANET as early as 1975) or dated concert recordings (such as musicologist Graeme Boone’s evocation of McCoy Tyner’s exact influence on Bob Weir; see “The Same Thing,” 11/29/66), it was the Deadologists’ sense of history that made the conversation possible.

And what struck me at the end of the conference is how young Dead studies is as a field, how much exciting work is left to be done in Deadology alone, and how much is unfolding right now, every week, in blogs and comment sections and Facebook threads, in addition to the more slowly accumulating academic canon. It is a confirmation of the Dead’s unceasing appeal, of the infinite depth behind the Steal Your Face lightning bolt, both symbolically and historically.

Refined in the early ‘70s, the famed skull logo was conceived by LSD chemist, soundman and Dead patron Owsley Stanley, and drawn by Bob Thomas, LSD lab assistant and co-founder of the Golden Toad, the free-floating acoustic world-music collective that became known as the Grateful Dead of the Renaissance Faire circuit. Not all roads lead to the Grateful Dead, and the Grateful Dead don’t lead everywhere, but not all roads are known.

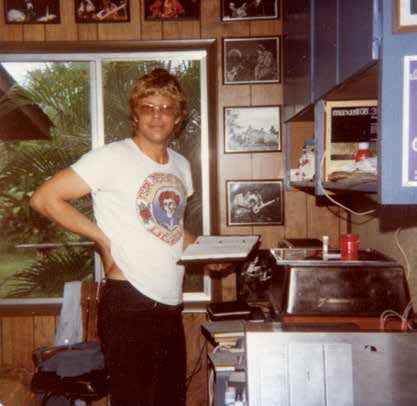

Dick Latvala and one of his trusty tape notebooks in the ‘70s.

Generally speaking, “Don’t read the comments” is sound advice in the digital age, but one corner of the Internet where comments are not only civilized but also essential, are the Grateful Dead historical blogs. In the 21st century, they are the natural habitat for a new species of Deadologist. With most of the band’s live tapes recovered, cataloged and remastered by professional and amateur audio enthusiasts, on official Dead releases or fan sites alike, what’s left to discover is information. And while the Dead’s body of music might be finite, information about the musicians and their recordings could conceivably turn out not to be. A group of loosely affiliated Deadologists have begun to make maps to find out if this is true.

At the broadest is the Grateful Dead Guide who (to name a few examples) have sourced biographies of oddball figures in the band’s lore, untangled myths, and much more. The Guide’s Dead Sources appendix is strictly devoted to reposting archival articles from 1965-1975, with detailed comment section annotations by site proprietor Caleb Kennedy. For one post, Kennedy used Google Translate and a knowledge of Jerry Garcia’s idiomatic Californian English to recover an interview published in French during the band’s visit to France in 1971.

“It’s kind of a fluke that I have a Dead blog rather than a Beatles blog or Hendrix blog,” observes Kennedy, who only came to the Dead in the early 2000s. “But part of that is because those guys have an extensive literature already, while the Dead had scarcely been written about yet in a substantial in-depth way. You know how a writer likes discovering virgin territory to speak! I’m a little surprised that, a lot of the field, I still have to myself. I thought by now more Dead fans would be doing this, but they aren’t quite as fanatical as I thought.”

If that sounds like a challenge, then it is, especially the word “substantial,” given the enormous shelf of extant Dead books, including—but not limited to—a half-dozen new titles last year, not to mention the three-volume Deadhead’s Taping Compendium. But Kennedy’s point is extremely well-taken, since his work docket is already overloaded, and he’s only dealing with the band’s first 10 and most psychedelic years, leaving two decades wide open for anybody else.

“All the current different Dead scholars, whether journalists or bloggers, have loosely marked out distinct, if overlapping, territory,” says Corry Arnold, who runs Lost Live Dead and Hooterollin’. “In general, I have benefited greatly from them sharing information, correcting errors, and commenting on my blog. I try to be as helpful as I can to others. This cooperation is one of the things that makes the Grateful Dead an ongoing, vibrant enterprise.”

Arnold, especially, steers away from thorny topics. He wants people to feel welcome to fill in the blanks, to come out of the woodwork and join the conversation with memories or even fragments. All of the Grateful Dead blogs work on this principle, but especially Arnold’s self-described “rock prosopography,” which builds bigger histories of Bay Area folkie circles. Like Kennedy, Arnold has a firm belief in the Internet’s long tail. attempted to reconstruct Jerry Garcia’s record collection, The Warlocks’ 1965 repertoire, and the exact studio overdubs on Europe ‘72. They’ve assembled complete lists of studio outtakes, presented simple

With clear post titles, the blogs put their information square into the Googleable universe. If there’s a question about a specific show, then perhaps eventually the answer will come looking for itself. A pair of posts about the Dead’s first trip to New York in 1967 yielded comments from both former Dead manager Rock Scully and a member of the Group Image, the psychedelic commune located on New York’s East Village who bonded, jammed and shared bills with the Dead.

It was here that the blogs became especially useful to me when researching my book; in this case, looking for signs of how the Dead’s Haight-born psychedelia met the East Village’s rough-and-ready interpretation on that first trip east, and how those two ideologies connected or differed. I learned (from the Village Voice archive) that there’d been a hippie-cop riot days before the Dead came to town. And who’d invited them to play for free in Tompkins Square Park? Did underground New York’s radical head ambassadors The Fugs play, too, as Jerry Garcia once remembered? They’re not mentioned in any of the newspaper accounts. The questions kept asking themselves.

Corry Arnold’s been at it a long time. He first saw the band in San Francisco in 1972, and began seriously researching by the late ‘70s, eventually landing a copy of the so-called Soto List, a pre-DeadBase printout of known Dead dates. Arnold “called the Grateful Dead Hotline every week—as we all did—but unlike everyone else, I wrote down and kept a list of every Garcia, Weir, and other spin-off band date. I also accumulated what information I could from old

magazines and tape boxes about Garcia and Weir dates in the ‘70s.” When DeadBase VII arrived in 1993 with GarciaBase and WeirBase, “the entire show list was mine, complete with my formatting and my mistakes,” says Arnold.

Another long-practicing Deadologist is Ihor Slabicky. Working from his home in Ridgewood, Queens, Slabicky’s first serious Dead discography appeared in the seventh issue of Dead Relix in late 1975, taking up three pages. Slabicky kept at it, adding more data and information, before going online in 1986, hopping on the Usenet and making contact with some serious Deadologists. His file made the leap from typewriter to text, and he has never upgraded to HTML, preferring the easy workflow. A Google search for “Ihor Dead discography” finds a file that’s nearly 200,000 words, approaching 600 pages if printed. That particular volume is a modest work in the unpublished Dead bibliography. A half-decade ago, Corry Arnold estimated his output at the equivalent of over 1,800 pages and then stopped counting. Caleb Kennedy guesses his at somewhere over 1,000.

Not all Deadologists work online, for that matter. In Germany, a Dead freak (who saw the band with their legendary Wall of Sound speaker array in Munich in ‘74) and longtime taper named Uli Teute has been collaborating with Volkmar Rupp on a massive Grateful Dead photo archive. “As of 2016, end of February, we are at about 8,800 pics,” Teute says, turning the old-time Deadhead sport of identifying photos into a semi-private catalog organized by date. “We have no copyrights to any of the pictures,” says Uli. “Some well-known photographers—or a legal representative of a photographer or [their estate]—sell their pictures on the Web. We do not want to take away from their earnings. Still, we will show pictures from the archive collection to prove facts otherwise unknown, in a sense used as a scientific source.” Someday, one hopes, they will cross-reference them by gear, facial hair, wardrobe and more. It has been said that if one is working on a project and the relevant photos exist, then one might wake up to discover an attachment-laden email from benevolent German Dead freaks.

One Dead scholar I was especially sad to miss at Albuquerque this year was Joe Jupille, who couldn’t make it down from Colorado. Joe is not an independent scholar in the literal sense of many of his colleague Deadologists. He holds a Ph.D in political science, a professorship at the University of Colorado Boulder, and is an associate at the Institute of Behavioral Science. Jupille’s perfectly titled Jerry Garcia’s Middle Finger blog is a smartly written journal of his expeditions into what he has dubbed the Garciaverse. Some of his particular interests include Garcia’s finances, his relationship with the Hells Angels, warmly annotated listens to all eras of the Jerry Garcia Band, bibliographies and generally anything-Garcia-related that doesn’t have to do with the Grateful Dead. Jerry’s just where it’s at for Joe Jupille.

At Albuquerque conferences in the past, Jupille has shown his in-progress visual representations of various dimensions of the vast Garciaverse, demonstrating the guitarist’s social connections to other musicians in relationship to his repertoire and other factors. He is still working on its best possible form.

In naming his work the Garciaverse, Jupille has nailed a distinct aspect of what it is the Deadologists achieve, on a level perhaps more conscious than their historical work: more episodes in the imaginary unscripted reality show of the Grateful Dead. Take Jupille’s post about the band’s canceled July 4, 1974 show in Oshkosh, Wisc., and cross it with details from Ihor Slabicky’s NedBase, where one discovers an account of members of the Dead drag-racing rental cars through rural Wisconsin in the summer of ‘74. (The latter site, of course, is a chronology of Seastones composer and frequent early ‘70s Dead guest Ned Lagin.) With the right amount of Grateful Dead reading, if one desired, all they’d have to do is sit back and let an episode write itself, imagining what the Grateful Dead might be talking about while out on the Wisconsin backroads over Independence Day weekend 1974, at the peak of Watergate, at the height of the band’s first stadium period.

The expanded universe reality-show aspect comes to the fore most vividly via the freeform Grateful Dead ahistorical blog known as Thoughts on the Dead.

“Some of it’s absolutely magnificent work,” says Dead archivist Nicholas Meriwether of TotD’s fact-laden kin. “Corry Arnold’s stuff is just amazing in every way, an awful lot of it is stunning. I do think that, often, what is missing from the work that’s been done outside of an academic context… just a little bit of input from the academic side could make it even more useful, even stronger.” But Grateful Dead Essays has begun incorporating footnotes into posts. The latest, “The Songs the Warlocks Played,” runs to 59 items.

Various cornerstone texts of Deadology are available used online, in prices ranging from $5 for The Grateful Dead Reader to a hefty $30 for the substantial The Grateful Dead and the Deadheads: An Annotated Bibliography. There are

also exciting new titles connected to the Grateful Dead phenomena, psychedelics, technology and counterculture that you can read, too, on sale at bookstores now.