So Much to Say: Revisiting Dave Matthews Band’s _Crash_ at 20

“Unh … oonh … unh-oonh-eee-oh.”

Say what? So starts “So Much to Say,” the lead track on Crash, Dave Matthews Band’s irrepressible, brawny 1996 LP, which has a birthday on Saturday. Believe it: It’s now been 20 years — yep, already — since this record was released.

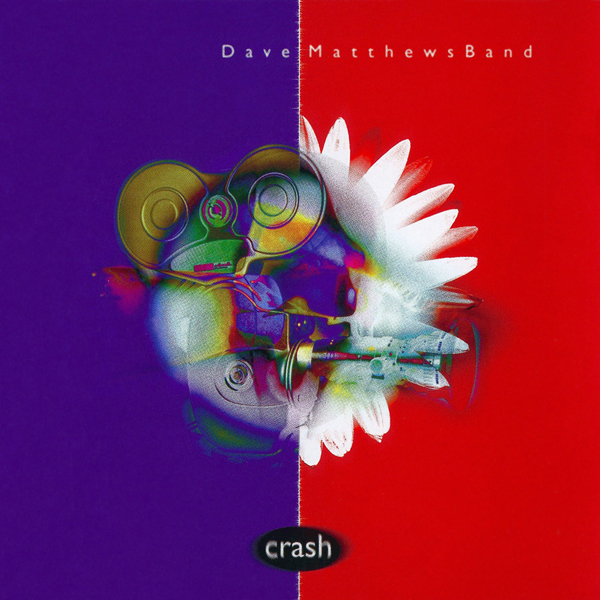

On a lark, producer Steve Lillywhite opted to keep the count audible to kick off the record (the voices you hear off-mic are Matthews and two overdubs of drummer Carter Beauford), and so from the start you get a quick hint to the atmospheric changes to come with Crash vs. DMB’s grassier, acoustic-molded major-label debut, 1994’s Under the Table and Dreaming. Crash is the record with weird, artsy cover, that indiscernible collage of I-still-can’t-tell-what against a simple, split-down-the-middle red-and-blue background. Very 1990s. But even if the album’s artwork is outmoded, the production, like all of Lillywhite’s work with the band, still holds up all these years later. “Proudest Monkey,” “Too Much,” #41,” “Lie in Our Graves” and “Crash Into Me” still sound like signature standouts of Lillywhite’s scrupulous designs.

On May 7, DMB will kick off its annual summer tour, this year’s coming on the 25th anniversary of the band’s inception. Without the triumph of Crash, Dave Matthews Band probably doesn’t transform to the phenomenon of DMB. It probably doesn’t reach a 15th birthday let alone a 25th. Pearl Jam, another quintessential, era-defining rock band of the past two and a half decades, is also celebrating 25 years of existence in 2016 and has made a decision in recent months to randomly play some of their albums live, in track listing order, on unsuspecting crowds. It would be an appropriate and incredible thing for DMB to do the same as a way of honoring their 25-year legacy, giving back to their fans and spicing up setlists, which have become somewhat stale in recent years. If Matthews has it in him to try this even at least once, Crash is the ideal candidate. It’s the LP that put the group on the path to superstardom for more than a decade, it’s the record with the most fan-friendly songs, and it remains the most mass-appealing studio effort the band has ever put out.

As with the 20-year UTTAD look-back in 2014, I again caught up with Lillywhite in an effort to get more perspective on the sessions and the nature of the band at the time of the recordings while assessing the legacy of the record so many years later.

“We wanted the album to be this much bigger animal, like a big dinosaur,” he said.

Crash was put to tape in October of ’95 through January of ’96. The band was eager to get back into the studio, and since it had a majority of songs already road-tested for years, the feeling was they could churn out another session quickly. The setting was the same; they’d record the majority of the album in Bearsville, N.Y., just as they had for UTTAD. But Lillywhite was not going to settle for a similar sound even though a lot of the Crash cuts were around for just as long and played as frequently as many of the UTTAD tunes. Until Crash came out, fans of the band considered “Two Step” of the same era and sound as “Dancing Nancies,” and the same of “Say Goodbye” and “Rhyme and Reason” and so on. Now, the songs are viewed different to an extent because their respective records are strikingly different (and that’s for the betterment of the band’s longevity). Upon arrival at the Bearsville studio, the band had just one request: They wanted to play, and record, while formed in a circle. No piece-by-piece, traditional studio steps, like UTTAD’s process. Lillywhite, an admitted control freak, embraced the change.

“With Crash, I wanted to change things up, because I think it’s always important,” Lillywhite said. “When I grew up with The Beatles, it was like a journey for me. What stood out for The Beatles was, every time there was a new song on the radio, you knew it was The Beatles but there was something about the sound that was evolving. They never stayed the same. In my experience with U2, we always tried to make sure we didn’t copy our previous success. Now, that’s very un-American. In America, you have success and then the second time around you copy that because you know it worked. But I, believing in art more than anything else, I wanted the band to take their fans on a journey.”

Lillywhite carried some of that late-’60s Beatles ethos with him for nearly two decades, as he considered drug-taking integral to the record-making process. Crash was one of the last records he recorded while still ingesting generous amounts of mind-altering substances. (He’s now nearly 19 years sober.)

“Crash was very much wake and bake, doing coke in the evenings and drinking large amounts of red wine,” he said. “My drug-taking, and I mean alcohol or anything that would change my perception of things, was all to do with my work. A lot of people would finish work and go and party. I would finish work and go and crash and need to recover. For me, I would smoke a joint and listen to the music and just get inspired.”

In turn, the band was as well. This time, much more than on the previous LP, Beauford would be allowed to show off his outrageous chops. The record wasn’t going to be clean and crisp. Listen closely and you’ll pick up on it: One of Crash’s strengths goes against trends of its era — it lacks reverb. It also has significantly more overdubs than UTTAD. In a risky but inspired move, Lillywhite took Matthews and Reynolds’ acoustic guitars and plugged them into electric amps on many of the tracks. Listen to “Drive In Drive Out,” “#41” and “Cry Freedom.” Those aren’t electrics (though Matthews did play the half-acoustic/half-electric Chet Atkins during this period). A wild experiment, one Lillywhite had never tried it before, and it worked.

“I didn’t want to use electrics yet,” Lillywhite said. “There we so many bands playing electric guitars that were like a chainsaw throughout the whole sound, like a buzzsaw. And I thought the intricacies of Dave and Tim’s guitar playing were so cool, that it would cheapen it, slightly, if on electric. We amped up the electric guitars. It gives the sound a whole different sort of sleaziness almost. Everything on this album is bigger than on the first album.”

Crash still kills. It has bite and bark. It manages to pull off a tough feat: a live feel with studio disciplines. Most of the album comes off like you’re hearing the band just moments after everyone checks their levels and tunes their instruments. A reason connected to that, and a big reason for the record’s success, was comfort level with the songs. Eight of the 12 Crash cuts were well-worn by that point. The only songs fleshed out or significantly tweaked in the studio were “Crash Into Me,” “Too Much,” “Let You Down” and, to a lesser extent, “#41.”

“Dave was in a good headspace and felt like writing and had gotten the validation of the public, which was amazing,” Lillywhite said.

Unexpectedly, Crash’s reputation has become a bit overshadowed in the 20 years since its release, at least when compared to the other two records in DMB’s “Big 3” and even more so against the backdrop of the dozens and dozens of influential LPs released throughout the ’90s. Within DMB’s early discography, UTTAD is the ever-important and still-beloved breakout, while 1998’s Before These Crowded Streets is considered by many to be the group’s magnum opus, without question its most ambitious and rewarding studio effort. But Crash? That is DMB’s best-selling record — by a solid margin. It’s sold well above 7 million units and was the album that vaulted the group into another realm of popularity thanks to “Crash Into Me.” The song that turned millions of fans (plenty of them women) onto Matthews’ music is an unsettling view into voyeurism, a delusional creeper’s internal vow masquerading as a delicate love song.

The trick of the damn thing is, it’s a beautiful tune. And the irony of Crash is that its standout song is unlike much of the rest of the album. It’s not aggressive, it’s not loud, it’s not pulpy or greased up. In the end, it’s one of the strongest yet simplest songs Matthews has ever written. That’s why it was such a huge hit, an unlikely breakthrough given it was the album’s third single, following “Too Much” and “So Much to Say” and released seven months after the record came out.

“That’s the one that got the moms,” Lillywhite said. “It was more of a crossover-type song.”

The man would know. In speaking with Relix earlier this week, Lillywhite was his typical honest, forthcoming, jolly self. He also offered up unprompted anecdotes, and since we’re on the subject of “Crash Into Me,” well, here goes.

“I can claim to be the first person ever to have made love to that song,” Lillywhite said, laughing as he recalled it. “My girlfriend at the time, who subsequently became my second wife and mother of my third and fourth children, she lived in New York (City). Every weekend I would go to New York from Woodstock and stay with her. I would play her rough mixes of the album. I remember one night taking a rough mix of “Crash Into Me” to her house and making the moves and going, “This is a great song for making out to,’ and who knows how many countless babies have been conceived to that song since. But I was the first!”

“Crash Into Me” was one of the biggest projects on the record. The music and song structure wasn’t typical of DMB’s repertoire at the point in its career. Lillywhite noted how the band sometimes had problems playing really simple stuff because they were such great musicians, but pop-like songs were not their speciality. Plus, most notably, Matthews couldn’t complete the song.

“Dave couldn’t get the lyric right for that, though,” Lillywhite said. “It took him a long time to get the verses. Because, all the vocals Dave would do, really, would be his typical no lyrics, just singing a stream of consciousness. That was the vocal for so long on the album. Then we came to Greene St. (a since-shuttered studio in New York City) to do the finished vocal. He just couldn’t unlock it. I remember him going to Charlottesville one weekend and coming back to the studio. And he walked into the studio with such a big smile on his face. And I said, ‘Dave, what’s going on?’ And he said, ‘I’ve got it! I’ve got it!’ He was so excited.”

The night before our interview, Lillywhite listened to the album in full for the first time in nearly two decades. He spoke of missing the late LeRoi Moore, who he affectionately called a “great foil” for his studio philosophies. One of Lillywhite’s tricks in working with DMB was to let inspiration and ideas form only after meeting the band and hearing rough cuts in the early album process. There was not a lot of outlining or “homework” as he called it. From there, he challenged them often, and he’d create sounds and emphasize certain aspects of songs that the band would only discover later, well after Lillywhite had sculpted the songs into ideas.

“Some things need to be done without talking about them, and they stay more magical that way,” Lillywhite said. “The band would play and I would mold and steer. It gave the album certain psychedelic qualities in some places.”

Moore’s use of baritone sax, an element missing on UTTAD, is one of the biggest stamps on the record. As is Reynolds’ nimble guitar playing, which is layered and serves as punctuation to the band’s sound. “Too Much” is the best hard-funk song DMB’s ever written, and Reynolds’ contributions on the album are a big reason why.

“I wanted to keep it looser,” Lillywhite said. “I wanted it to be a little more, I think sleazy in the nice connotation of the word. Something greasy, something a little bit more … not quite as uptight. The song ‘Too Much’ is definite example of that. When you’ve gotta song like that, you’ve just gotta go for it. It’s a juggernaut of a song. It’s about excess, and so much about that album was about excessiveness and more expansive than Under the Table.”

Lillywhite had a crafty way of connecting themes (listen to the way the cowbell and blocks on the ending of “Too Much” are similarly brought back on the fade-in to “Tripping Billies” seven tracks later) and pushing the band to expand its sound while constricting song structure in a lot of cases. Beauford was implored to play two snare drums on “Two Step” to get the shuffle in stereo feel. The segue of “#41” into “Say Goodbye” highlights one of DMB’s greatest studio achievements. The intro to “#41,” the way the mood is set with each band member occupying a different sonic space, remains one of the albums highlights. As is the song’s post-chorus jam, which shifts from Reggae-ish bop to Moore’s signature album statement on tenor sax. When people refer the group’s “jazzy” leanings, this is the best of it.

From the paradiddle domination of “Drive In Drive Out” (all these years later, it now seems this is the band’s most underrated song) to the atmospheric and uplifting middle section “Lie In Our Graves,” the gamut of the group’s arsenal is almost entirely covered on the record. The album has rarities, smash hits, deep cuts, hard edge, soft approaches. No record of theirs is as wide-reaching while all the time staying as centered to the origins of the core five’s sound.

The success of UTTAD, combined with an expedited 18-month turnaround to put out Crash, yielded huge returns. The record debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard charts. Crash catalyzed a record-setting run. Every DMB LP since (six of them) has gone No. 1 in the first week. No band anywhere in America has done the same since Billboard began tracking album sales. In an era of influential music videos, the visual creativity behind all three big singles helped DMB stay in MTV’s rotation. The record landed the group its first Grammy (“So Much to Say” took Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal in 1997), and earned another nomination in the same category for “Crash Into Me” in 1998.

Is Crash a defining record of the ’90s? Some might immediately think no, but don’t be so dismissive. It sold exceedingly well and led DMB to opening for legends like Bob Dylan and Neil Young. Crash’s quick returns also wound up getting the band booked at Madison Square Garden for the first time later that year, a two-nigh stand. The songs are still played on myriad radio formats, and “Crash Into Me” undeniably became one of the biggest hits of the decade.

“Records now are not something to do with the time they were made,” Lillywhite said. “Everyone who makes records now is trying to please everyone all the time.”

DMB wasn’t trying to do that. It was merely trying to solidify itself while not being affixed to a genre aside from “rock,” the definition of which was changing by the year in the ’90s. Crash did that and a lot more. It elevated the band’s appeal, sparked gigs across the Atlantic Ocean and earned the group critical success among its peers. Crash ensured there would be no sophomore slump, but beyond that, it proved the group could be as powerful in the studio as it was live. It wasn’t a risky record, but it was a zealous one, and that proved pivotal in pushing the band forward to its most critical and creative period: writing, recording and touring for Before These Crowded Streets.