Relix Revisited: The Brent Mydland Years: An Appreciation of the Grateful Dead in the 1980’s

In celebration of what would have been the 64th birthday of Grateful Dead keyboardist Brent Mydland, who passed away in 1990 after playing with the band for over a decade, we present this piece that originally ran in our August 2005 issue. Here, longtime Dead journalist Blair Jackson, author of Garcia: An American Life and former editor of Golden Road, revisits an unappreciated era in the history of the group.

Dick Latvala, the Grateful Dead’s famous vault-keeper and namesake of the Dick’s Picks series of historic Dead recordings he shepherded from its inception in 1994 until his death in 1999, once told me that he would be happy spending all his waking hours listening to Dead music recorded between 1968 and 1974. “There are a few shows from ‘77 I love, a couple from ’78, various others scattered through the years, but I don’t need the other stuff. For me ‘73-’74 was the peak.” And he laughed the deep, rumbly laugh of someone who had spent much of his life sucking on bongs and cigarettes.

This is not an uncommon view among older hard-core Deadheads – that the late ‘60s and early ’70s represent the apex of the Dead’s career in terms of the quality of their songwriting, their onstage chemistry and the adventurousness of their playing. Fundamentally I agree with that assessment, too, and it’s not just because I first heard the band in 1969 and started going to shows regularly in the spring of ‘70, so that version of the band corresponds with my own Coming of Age. Clearly, the music of that era is a cut above.

But here’s a secret: I loved every period of Dead music, and I actually had more fun going to see the Dead in the 1980s than in the ‘70s. The ‘80s was a very different kind of Golden Age of the Dead: It was the era of the Dead’s greatest popular growth and of widespread networking among Deadheads; and creatively, it found the band moving in a number of interesting and compelling directions. The vast majority of Deadheads never saw Pigpen (who died in 1973), never saw Keith and Donna (who left in early 1979). No, for hundreds of thousands of Deadheads, the lineup with Brent Mydland on keyboards defined their live experience, and they loved that band with all the passion and mystical fervor of the few Heads who first encountered the psychedelic beast at the Carousel Ballroom in 1968 (or even earlier). And why not? The Dead with Brent was a great band, too, and obviously as capable of blowing minds as earlier incarnations had been. It was the perfect band for that time and those fans – for the decade of the staggering growth of the loose, laissez faire Deadhead counter-culture, and the concomitant rise of the band’s own commercial fortunes during a period when so many forces in American society were moving in the opposite direction, towards rigidity and conformity.

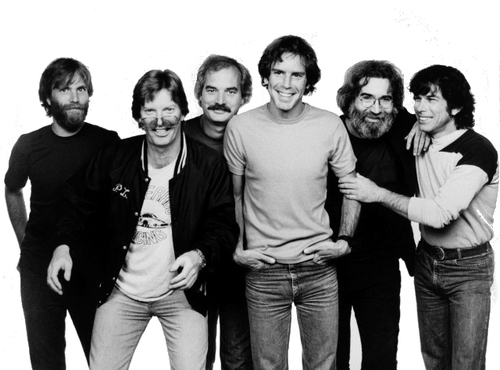

For a band that evolved gradually through the years, constantly adjusting to minor and major changes in personnel (T.C.‘s brief tenure, Mickey leaving for five years, the Godchaux’s saga) the addition of Brent actually represented a fairly major shift in the group’s sound. The somewhat monochromatic keyboard approach of Keith Godchaux (particularly his last couple of years) was replaced by a much more colorful and insistent keyboard sound: Brent was a Hammond B-3 master of the first order and also adept at synthesizers; both opened up the Dead’s music to exciting new possibilities. He was a much better onstage singer, technically, than Donna Godchaux had been, so immediately the group’s harmonies took on a new power and vitality. He also was a dynamic performer, throwing himself into his singing and playing with abandon, his long blond hair flying with each emphatic pounding of the keys. Garcia, who was still at the beginning of a long slide into addiction when Brent joined the group, was clearly buoyed by his presence.

At the same time Brent was joining the band, there was a major transformation, too, in the percussion section. This wasn’t a personnel move; it was a shift in equipment and approach. In the early spring of 1979, Mickey Hart had been asked to create a percussion underscore for parts of Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam War film then in post-production, Apocalypse Now. Mickey responded to this challenge by assembling a huge number of percussion instruments from around the world and also having a number of custom ones built. He brought fellow “Rhythm Devils” Bill Kreutzmann, Greg Errico, Brazilians Flora Purim and Airto Moreira and others into the recording studio, and together they spent days exploring different aspects of the film’s story through percussion, jamming for hours on end. From small woodblocks and bells to giant frame drums and the marvelous contraption known as The Beam (which had piano wire stretched across and aluminum I-beam; when amplified it was perfect for simulating the sound of a napalm attack or other sinister sounds of war), they tapped into the primal power of the myriad instruments. The percussion journey didn’t end with that soundtrack, however. Mickey and Billy used the occasion of Brent’s joining the band to re-structure their percussion setup onstage, incorporating many of the instruments they had employed for the film, including The Beam, various gourds and shakers and the great circle of huge, thundering drums which became known as The Beast. From the first shows with Brent in the April of 1979 through the final Dead concert in July 1995, Hart and Kreutzmann completely re-defined the rock show “drum solo” by opening it up to the entire world of percussion and, in later years, using advanced electronics to alter the sound even more. It was music with roots as deep as mankind’s own, and with literally no boundaries. In the 1980s, the Rhythm Devils’ portion of the show, along with the group space jams that always followed, were some of the freest, most mind-bending music being made on planet Earth, and its legacy is as important as the Dead’s rockin’ side.

A year into Brent’s stint with the band came another important milestone: the Dead’s fifteenth anniversary in 1980. The group celebrated by performing acoustic sets for the first time in ten years at extended series of shows at the Warfield Theater in San Francisco and Radio City Music Hall in New York. Unlike the Dead’s acoustic sets in 1970, which mostly featured Garcia and Weir playing as a duet, with just occasional accompaniment from the others, the 1980 sets found all six members playing together as an exquisite chamber ensemble that moved easily through folk, bluegrass and a number of Grateful Dead tunes, ranging from open-ended vehicles like “Bird Song” and “Cassidy,” to “China Doll,” with Brent on harpsichord, the beautiful love ballad “To Lay Me Down,” and “Ripple,” which always got everyone singing along. The acoustic sets were beautifully captured on the 1981 live album, Reckoning. The Dead never played acoustic sets after that, but the experience appeared to rekindle Garcia’s interest in folk music – later he started playing occasionally in an acoustic duo with John Kahn, and eventually with the Jerry Garcia Acoustic Band and then, in the early ’90s, with David Grisman.

Though the Dead wouldn’t put out a studio album between their first effort with Brent, Go to Heaven, in 1979, and 1987’s breakthrough smash In the Dark, their profile continued to grow through the early ’80s. There was considerable national publicity surrounding the Radio City shows and the 15th anniversary in general, and then they were seen by their biggest audience ever when they appeared on Saturday Night Live in April 1980 promoting Go to Heaven. A Showtime TV special and a video called Dead Ahead were culled from the Warfield and Radio City shows, as well, giving the band its highest visibility in years.

The other thing that happened in the first few years of Brent’s time with the band is the group started playing more interesting venues than they had previously. In California, a succession of wonderful facilities opened up to the group: The Oakland Auditorium (later called the Kaiser Convention Center) in 1979; the Greek Theatre in Berkeley in 1981; Frost Amphitheater on the campus of Stanford University, and the Ventura County Fairgrounds (north of L.A.) in 1982; Irvine Meadows amphitheater south of L.A. in 1983. In the Midwest, Alpine Valley in Wisconsin was a popular destination beginning in 1980, and Red Rocks in Colorado, which the band first played in 1978, became a magnetic Mecca for touring heads as the years passed. And though places like the Hampton Coliseum in Virginia, Nassau Coliseum in Long Island, the Hartford Civic in Connecticut, the Centrum outside of Boston and Madison Square Garden in New York were really just soulless sports arenas, they, too, seemed to take on a special glow that allowed them to transcend their utilitarian roots whenever the Dead came to town.

Throughout the 1980s, the Deadhead legions continued to grow. By the early years of that decade, the loose Deadhead taper network was firmly established and thousands of new fans thronged to Dead shows just from having been turned onto the group by friends who had live tapes. Beginning in 1984, too, the Dead established formal taping sections at their shows for the first time, further increasing the number of people who were making (and trading) tapes. In the West, Bill Graham Presents conceived of regular weekend getaways for the Dead and the Heads every spring and summer, at the Greek, Frost and Ventura, as well as exotic locales such as the downs in Santa Fe and Austin, the Aladdin Casino in Las Vegas and the tiny Hult Center in Eugene, Oregon.

White-collar Deadheads could fly in or drive to these weekend jaunts, and Deadheads who weren’t tied to jobs either because they were students on summer break or simply unemployed, found that following the band for weeks at a time – camping out, sleeping in tour vans, crashing with friends or overpopulating the hotel rooms of other Heads – was both feasible and incredibly fun. As the legions caravanning along the Dead’s tour routes grew, so did the number of people who tried to support their touring by selling crafts outside of shows. What started as a few folks spreading their wares on blankets outside the Oakland Auditorium in 1979 had mushroomed into a full-on bazaar in just a few years. And it wasn’t just hippie peddlers selling homemade T-shirts, stickers and the odd veggie burrito. After a while, larger businesses, with huge racks of Guatemalan clothing, and food trucks equipped with stoves and grills, became fixtures in the parking lots outside of shows, and the scene started to attract hundreds – then thousands – of people who didn’t particularly care about seeing the Dead, but who liked the commercial circus outside. This led to considerable problems for the Dead in the second half of the ’80s, when various cities and towns refused to allow the band to play there because of the uncontrollable hippie city that sprang up around each show, whether it was in the middle of a city or in more rural locations.

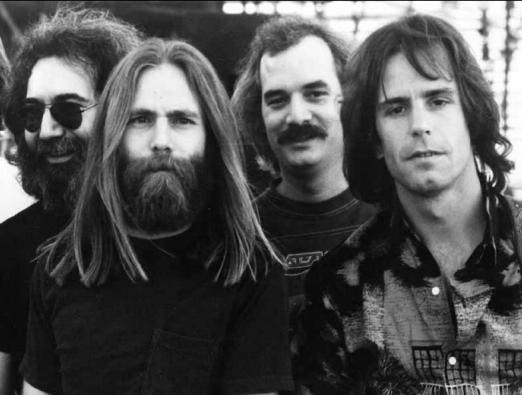

Though Garcia’s ballooning weight and sickly pallor in the early and mid-‘80s were cause for concern among some Heads, there were many excellent shows coast to coast, and musically the group was still willing to take chances. In 1983, the popular triumvirate of “Help on the Way,” “Slipknot” and “Franklin’s Tower” returned to the repertoire. “Dancing in the Streets” came back in its old, non-disco arrangement. Brent and Phil became singing partners on several fine tunes, including “Gimme Some Lovin’,” “Keep On Growing” and Brent’s own “Tons of Steel.” Other new songs from the band ranged from Hunter and Garcia’s anthemic “Touch of Grey” to Weir and Barlow’s potent polemic, “Throwing Stones.” “Hell in a Bucket” was a powerhouse rocker sung by Weir, while Garcia’s “West L.A. Fadeaway” was a slinky, slightly nasty blues. “St. Stephen” and “Dark Star” made brief cameos in ’83 and ’84, respectively, while songs such “The Wheel,” “Crazy Fingers,” “Comes a Time” and others breathed with new life in their Brent-era revivals.

Garcia’s near-death from a diabetes-induced coma in the summer of 1986 nearly stopped the ever-accelerating juggernaut for good, but rather than causing the group to lose some momentum from what had been a straight upward climb in popularity during the first half of the decade, the brief forced hiatus, and then Garcia’s return in December of ‘86, only increased the public’s interest in and affection for the Dead. By the middle of 1987, the group had finally finished their first studio album of the ‘80s, In the Dark, which hit the Top Ten and yielded the group’s first bona fide hit single, “Touch of Grey.” The clever video for that song, with skeletons performing onstage, went into heavy rotation on MTV for a spell, and a long-form live-and-conceptual video directed by Garcia and Len Dell’ Amico called So Far also became a best seller. A tour of stadiums featuring The Dead and Bob Dylan (who were backed by the Dead) that summer was extremely successful, and the momentum of ‘87 led to even bigger tours the next couple of years. And whereas ’87 was really the “comeback” year, ’88-’90 were the peak of the Brent years, with the band playing with tremendous energy and imagination, regularly dusting off old classics and introducing a number of well-received new songs, as well, including Garcia’s “Foolish Heart,” “Built to Last” and “Standing on the Moon,” Brent’s “Just a Little Light,” “Blow Away” and his cover of “Hey Pocky Way” and Weir’s “Picasso Moon” and the powerful but controversial “Victim or the Crime.” The introduction ofMIDI technology, which allowed the musicians to limitlessly expand the timbral possibilities of their instruments – letting say, Garcia’s axe sound like pan pipes or a bassoon or a breathy choral voice, or Brent’s keyboard to ape a fiddle or marimba – also took their music to some fascinating new spaces.

A few days after the end of the band’s early summer tour in 1990, Brent Mydland died of an accidental overdose in his Contra Costa county (Calif.) home, abruptly shutting the door on an 11-plus-year period of relative stability and unparalleled growth for the Dead. A mere two months later, the Dead would be back on the road with Vince Welnick and Bruce Hornsby filling the keyboard slot together and taking the Dead’s music in some other new directions. But there is no question that Brent’s death was, as Garcia put it, “crushing,” and that it was the end of a special time in the Dead’s history. There would be a number of fine shows and tours in the early ‘90s – and thousands of new fans would find and embrace the Dead in the Vince era – but for many Heads a certain spark went out with Brent’s passing. With Garcia’s precipitous decline during 1994 and ‘95, the ’80s looked more and more like Glory Days past, receding in the rearview mirror on the ol’ tourmobile. The ’80s felt like a time when Deadheads ruled the land, and the scene was truly, as the song “Might As Well” said, “one long party from front to end.”