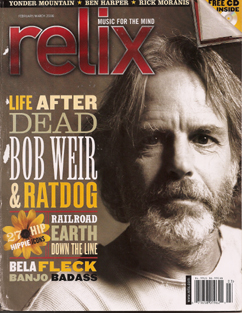

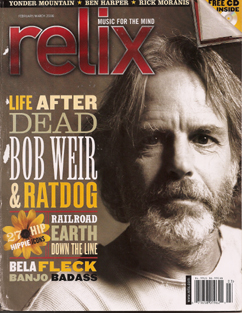

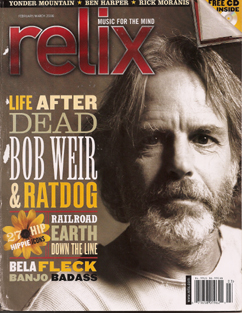

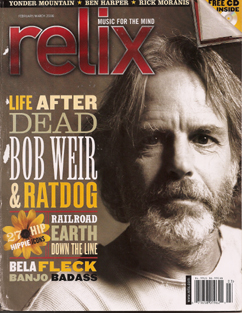

RatDog’s Return: Bob Weir and Life After Dead (Relix Revisited)

To mark the debut of the new RatDog Quartet, with Bob Weir, Jay Lane, Robin Sylvester and Jonathan Wilson (come back later today for a photo gallery), we revisit this cover story from our February/March 2006 issue.

Bob Weir spent the night at his Mill Valley home before arriving for the RatDog show in December at San Francisco’s The Grand, a thousand-seat former movie theater built shortly after the 1906 earthquake. With his Grateful Dead sideline band on the road virtually non-stop since summer ended, the brief respite at home was a welcome reprieve from road food and sleeping in the bus.

His voice was showing signs of singing five three-hour shows a week and he was, by his own estimate, “a little crispy.” But Weir, who showed up just late enough for soundcheck that the rest of the band was already onstage, has been straining his voice since he joined the Grateful Dead as a 17-year-old high school dropout 40 years earlier.

“I’m going to need vocal rest when I get back,” he said. “But I know some tricks and there are some things you can do with your voice like this that you can’t do otherwise.”

While assistant tour manager and longtime Dead publicist (and biographer) Dennis McNally scurried around taking dinner orders for band and crew, Weir retreated to the luxury coach that took him and his band to 90 concerts last year. McNally went over an email he composed for Weir to send to a terminally ill Deadhead. The coach has wireless internet access. Co-manager Cameron Sears climbed aboard to show Weir next year’s calendar and discuss some dates for spring. Production manager Chris Charucki appeared and wanted to talk about keeping the computerized, psychedelic light show the band had been carrying on the West Coast dates. Weir gave everybody his attention, but appeared most animated talking with a friend from his flag football team, the Mount Tamalpais Chiefs, checking the whereabouts

of his other team members to see who was going to be at the show that night.

“It’s the most fun you can have that’s legal,” Weir said, “although some of our huddles may not have been strictly.”

Life comes to Bobby Weir, 58, not the other way around. In the past few years, he has settled into a comfortable groove. He married his beautiful wife, Natascha, six years ago and they have two young daughters, four and eight years old. Last year, he finished a two-and-ahalf-year remodel on the Mill Valley home with the treehouse recording studio where he has lived for 30 years. He grew a salt and pepper beard that lends him a more than passing resemblance to Commodore Whitehead, the jolly old fellow who used to appear in advertisements touting “Schweppervescence.” With a pair of rimless glasses, he seems to be summoning his inner Garcia. But Weir and his more famous guitar partner in the Grateful Dead were never really alike at all – more like yin and yang.

Where Garcia was extravagantly verbal, jolly and ceaselessly witty, his younger associate has always been taciturn, placid and contemplative. Weir was the sex symbol of the band, a good-looking young guy with soulful brown eyes and a long chestnut mane. A dyslexic who found school impossible – he flunked out of seven different high schools – Weir is nevertheless a searching and penetrating thinker who pursues his many intellectual curiosities and, even though he still finds reading difficult, will do the heavy lifting for a subject that interests him.

“He’s smarter than you think and he uses that as a weapon,” said his Grateful Dead bandmate Mickey Hart. “You think he’s spaced – and he is – but meanwhile, he’s in there the whole time going tick… tick… tick.”

A few minutes before showtime, which he also sets back a few minutes, Weir moves to the back of the bus to change clothes for the show. He returns in his trademark Birkenstock sandals, khaki shorts, white Mexican peasant blouse – all dressed up and ready to rock. Onstage, RatDog cranks up with a 15-minute version of the Dead staple “Shakedown Street,” segues smoothly into “New Minglewood Blues” and finally comes to a brief rest twentyish minutes later after grafting a supple “She Belongs to Me” on the end of the three-song jam. Weir remains one of the great interpreters of Dylan, someone who actually manages to get inside Dylan’s oblique songs and make them his own, although this accomplishment is probably not widely recognized (Dylan knows it – but he would).

Perhaps precisely because of his laconic, unassuming character, no major rock star has probably ever received less attention for an accomplished solo career than Weir. He recorded his first solo album in 1972 – the highly acclaimed Ace, which contained the original recordings of the Dead standards “Playing In the Band” and “One More Saturday Night.” Over the years, he has recorded a thoroughly respectable assortment of solo projects under his own name and with his previous sideline bands Kingfish and Bobby and The Midnights, in addition to his contributions to the Grateful Dead proper as one of the two main songwriters and vocalists in that esteemed band.

RatDog first started more than ten years ago, shortly before the death of Garcia in 1995. The original band grew out of the stage and studio work Weir had been doing with bassist Rob Wasserman, a Marin County native with heavy chops who has worked with a variety of important musicians and recorded a well-regarded series of duets and trios.

With harmonica player Matthew Kelly, a friend of Weir’s back to private school days who also played in Kingfish during the ‘70s, Weir drafted drummer Jay Lane, who was a key player in the burgeoning San Francisco new-wave jazz scene around a South of Market niterie called The Up and Down Club. Lane belonged to a groundbreaking, multicultural Berkeley rock band called The Freaky Executives, a multi-racial ten-piece outfit that merrily blended world music genres with rap, rock and hip-hop in the mid-‘80s. He also played in the original version of Primus.

But when Weir found him, Lane was playing hard bop in hipster dives with a group called Alphabet Soup that became something of the farm team for Weir and RatDog.

Before the first Furthur Festival tour the summer after Garcia’s death, a repertory company that included Dead drummer Mickey Hart, Hot Tuna and others intended to appeal to the Dead’s audience, Weir added historic pianist Johnnie Johnson, the 72-year-old pianist who played on all the old Chuck Berry records. The band concentrated on ballads and blues and was hardly an audience favorite on the tour.

Slowly RatDog evolved. Lane introduced to the band young Berkeley jazz saxophone phenom Dave Ellis, who worked with Lane in the original Charlie Hunter Trio. Kelly mustered out. So did the aged Johnson (who died last year at the age of 80). Keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, who played in Ellis’ group and had worked with Lane, too, at local jazz clubs, joined in 1997.

Guitarist Mark Karan, a longtime Marin County guitarist who had moved to Los Angeles and was working with Dave Mason when he got the call, hooked up as second guitarist with The Other Ones, the 1998 Dead substitute that featured Weir, Lesh and Hart from the original band. He joined RatDog, after the jazz-rooted Dave McNabb proved an ill fit, playing only nine shows. “Bob has a real affinity for jazz, whether it’s what he plays, it’s what he’s fascinated by,” says Karan. “So initially, I think he was fascinated by the fact that he could have a jazzish guitar player in his thing. But what worked out happening was that he needed somebody who was a little bit more rock-based, if not Grateful Deadbased, at least having a little bit more handle on Americana and some of the musical forms that the Grateful Dead stemmed from.”

Saxophonist Kenny Brooks of Alphabet Soup replaced Ellis, who quit the band in 2000 to spend time with his wife and young family. The final piece fell into place three years ago, when British rock bassist Robin Sylvester, a fixture on the Marin County club scene for many years, took over from the virtuoso Wasserman. “Rob was great in small ensembles,” said Weir, “three or four pieces. Any more and he just gets in the way. He’s a very busy fellow.”

While the living Dead managed to somehow put some of the band’s former members in various configurations on the road – including Weir in every different grouping – playing amphitheaters almost every summer since Garcia’s death, RatDog has toured incessantly in between, playing clubs and theaters in the spring and winter.

RatDog was slow to pick up speed. It took a number of years before the band found its groove. But the intent was never to create a Grateful Dead cover band with Weir as vocalist, but to explore the actual core of the Grateful Dead experience, the ensemble improvisations where each musician is an axis on which the geometric sound of the band shifts. After Sylvester joined the band, RatDog began to fulfill that unique, elusive vision.

“All of a sudden, we had somebody who was laying down the bass like a bass player, and we began jelling into a rock and roll band,” says Karan. “I think that we still have a whole lot of jazz influences, it’s impossible to get away from that with Jeff and Kenny in the band… But with Robin, Bob and myself, half the band is coming from a more traditional place. And now it’s really become, I think, the hybrid that Bob was looking for all along. It’s an improvisational rock ensemble with a whole lot of jazz underpinning.”

Since its inception, the band’s modus operandi has been to sort of figure things out in the moment, and to not overthink, or rather, over-rehearse. So, of course it took some time for the band to get good, says drummer Lane, but finally they’ve gotten it right.

“Anybody can get a band together with some happening players and rehearse, rehearse, rehearse,” he says. “But to get a band together with guys who have to kind of figure it out on their own, you end up creating something more like the Grateful Dead…I feel like RatDog has gotten to the point, what we’ve figured out on our own, we’re using that to communicate with each other and take more risks… We’ve been a band for so long, we’re doing the stuff that bands do, all unexpected dynamic drops, and real off the-cuff things. It’s like a well-worn baseball glove. It feels real comfortable.”

By the end of the first set at The Grand, the band reached critical mass. With Weir stoking the engine with his angular, immediately identifiable if sometimes downright weird rhythm guitar playing, guitarist Karan cast dancing silvery lines over the burbling, driving sound. The capacity crowd writhed and shook, half not old enough to have seen the Grateful Dead play and remember it. A four-year-old girl chased a balloon in the back, running underfoot of the dancers.

“He has a carefully crafted style of rhythm that was like the missing puzzle piece in Jerry and Phil,” Lane says of Weir. “It’s almost like if you take one part out of it, probably any part, and it’s kind of weird. So when it was just him without the lead guitar in there… I came from a very strict funk/R&B background, and this – not knowing the Grateful Dead – it was like jamming along with one little piece of it.”

Among the three guitars Weir played at The Grand was the Parber Telecaster, an instrument with a back-story worthy of Ripley’s Believe It or Not. A few years ago, Weir, who was raised by adopted parents, met his birth father, a retired Air Force colonel who never knew he fathered the child who had been put up for adoption and had raised four sons of his own. All of Jack Parber’s boys were musical, but the oldest, James Parber, actually played professionally, working local clubs as lead guitarist with Lawrence Hammond and the Whiplash Band and a group led by former Commander Cody and his Lost Planet Airmen vocalist Billy C. Farlow.

In 1979, James came down with spinal cancer and spent the next 12 years going through an agonizing, slow death under his parents’ care. After he died, his family divided instruments among themselves. After Weir made contact with his father and struck up a warm, endearing friendship, he and his wife used to take the kids up to spend the night at the Parber’s house. Every time he did, he foundhimself having to step over or push aside a beat up guitar case containing a mangled electric guitar, pickups off the moorings, strings all broken. He finally asked the Parbers if he could take the guitar to have his tech crew look it over and they replied something to the effect of “What took you so long?”

Rehearsing with the group that had decided to reclaim the band’s original name and go out as the Dead in 2003, Weir took the guitar to its Novato headquarters. His roadie returned in a few minutes with the guitar

cleaned up, the pickups properly mounted and a new set of strings. Weir, who had been having problems pulling the band’s sound together, tried on the guitar.

“The Telecaster has a thin, reedy sound,” Weir said. “It was instantly perfect. It cleared out a lot of clutter and made the whole band sound gel.”

Noticing a small five-figure serial number on the back, Weir asked the roadie to inquire at the Fender factory. Yes, indeed, they reported back, that is an original first-year, 1956 production model Fender Telecaster, worth as much as $75,000. Weir has played the guitar on every show since. James Louis Parber never made the big time, but his guitar did. His brother Christopher Parber – Weir’s newly discovered half-brother – was backstage at The Grand now that he’s family.

The 90 dates RatDog played last year represents a schedule as heavy as the Dead’s at that band’s peak. Sears and his management partner, New Jersey-based impresario John Scher, have already booked three nights at New York’s Beacon Theater in April and Sears was on the bus before the Grand show talking to Weir about doing an acoustic solo appearance at the annual Merlefest at Doc Watson’s farm. Weir apparently likes to work just about as much as he can.

“I keep getting better at it, too,” he said.

The adopted child of a kindly, privileged couple, Weir was raised in stately Atherton, an exclusive suburb outside San Francisco. He played football and track in high school, but he was never successful at school and quit entirely after joining the band that became the Grateful Dead. He quite literally grew up in the Grateful Dead.

Weir was the baby of the group and his movie star good looks and shy, inarticulate manner made him a heart pang to many of the ladies in his audience. As one of the band’s two main vocalists, Weir sculpted the front end of the Dead’s sound both as lead vocalist and harmonizing with Garcia. He sang lead on many of the band’s most well-known pieces, specializing in rave ups such as “Samson and Delilah,” “Sugar Magnolia,” and “Truckin.’”

Through virtually the entire 30-year career of the Grateful Dead, Weir also worked as a solo artist. With the long, slow evolution of RatDog, he is comfortably ensconced in a creative environment where he is entirely supported by his associates and doesn’t have to exercise any leadership. He is the rare example of a hands-off bandleader. At rehearsal, he shows up and drummer Lane has picked songs from the Dead songbook for Weir to sing. RatDog rehearsal is a distinctly low-key affair; no roadies running around setting up equipment and doing errands, no girlfriends or anybody hanging out. Weir operates the band’s sound system himself. He is an entirely low-maintenance rock star.

On the Dead’s last summer tour, for example, the band booked medium-price hotels in an effort to save money. As the bus rolled out of Boston for New York, one of the other members decided he wanted to stay behind and catch a symphony matinee. He had his family with him, so he had checked into a four-star hotel suite, which he kept for his stayover, as well as renting another one for his family, who went ahead to New York without him. While his bandmate was renting two expensive hotel suites in two major cities, Weir was asleep on the bus. When the band arrived at the medium-priced hotel in Manhattan, he declined to wake up and check-in. Instead he went with the bus to the New Jersey motel where the crew would be staying and continued sleeping on the bus in the Holiday Inn parking lot.

At The Grand, RatDog swings into a mighty version of “He’s Gone,” a song originally written about a dishonest business associate ( “he’ll steal your face right off your head” ) that now inevitably recalls Garcia. Friends say it took Weir years to even begin to process the loss of the extraordinary figure who loomed over his band and their lives for so long. He went for three years without a lead guitarist in RatDog. Dave Ellis has joined the fray at The Grand, taking the stage with his old comrades in the second set for the first time since he left the band five years earlier. He and Brooks give a honking horn section to “That’s It for the Other One,” to their own great, obvious delight.

Weir leaves the stage and the band slowly drifts into some authentic hard bop, Ellis and Brooks screeching and belching, Chimenti clanging underneath. Off the road with RatDog, these guys can often be found playing jazz in their old haunts like Bruno’s in the Mission district. RatDog has suddenly, seamlessly transformed into Alphabet Soup. It was never far from the surface with these guys, but now they were swimming in it, blowing molten jazz. The kelp dancers in the back drooped. Ellis and Brooks tossed fiery lines back and forth. The music made an intense glow and went somewhere else. It was a fabulous tangent, the sort of exciting, spur-of-the-moment sidetrip that originally made the Dead famous, a step outside the rest of the evening’s fare and the only real musical surprise all night.

The band brought the concert to a rousing finale, with a two-song encore of The Beatles’ “Revolution” and the Dead’s anthemic “Touch of Grey.” The audience filed out sated. The huge basement dressing room filled with old friends and family. Weir’s wife, Natascha, busied herself, while Weir bummed a cigarette and tossed back a bottle of Guinness. The crew started loading out the gear and finished producing the three-CD recording of the evening’s performance, a hundred copies of which are sold to the crowd at every show and delivered within 15 minutes of the conclusion. The buzz and hum that attend a happy backstage after a good gig is easy to bathe in. Weir, however, has something on his mind.

He is annoyed at the reception accorded the band’s jazz diversion, especially the Deadheads who went limp ( “I hate those guys,” he said, “they only like it when it’s an old Dead song.” ). Weir is not going to stifle his creativity – or his band’s – on the whims of an audience. If they don’t come along on the ride with him and the band, what’s the point of them being there? He is not in the entertainment business; he’s a musician.

“Jazz deserves to live,” he said. “Jazz musicians play with open ears. On a good night, the Dead listened to each other. The jambands today, they listen to each other as hard as they can. But they’re young and they don’t have the vocabulary to take it downtown and drive it around.”

It wasn’t long after midnight that the coach pulled out of the alley behind The Grand for the four-hour drive to Reno and the next night’s show.