Pretty Lights: Making the Walls of the City Quake

Derek Vincent Smith is a city kid – if you consider Denver, Colo. a city. Its expansive landscapes, oversized sidewalks, Lego-like architecture, party atmosphere, permissive attitude and high altitude certainly all come into play in the music that Smith makes under the tag Pretty Lights. He concocts his electronic audio mosaics – which paint the numbers between hip-hop, soul, grime, dubstep and dance music at large – in a sound lab in Denver’s warehouse district. The studio is housed in a rented loft space inside a reconstituted factory whose bricks were originally shipped from the East Coast in the 1940s. Vintage.

The loft, located just 15 blocks away from the apartment where Smith has lived with his photographer girlfriend since moving from Fort Collins, Colo. at the end of 2009, also serves as Pretty Lights’ headquarters.

“We have about six different desks,” Smith explains, taking me on a virtual tour of the office, noting designated areas for his production manager, office manager, social media manager, lighting designer – yes, the one who makes the lights so pretty – and even a video station where the Pretty Lights team can work on multimedia content for the tours.

At first glance, none of what Smith and his team have done seems all that revolutionary. But if you so much as scratch the surface, then you’ll see that – if Plato was right and the walls of the city really do shake when the mode of the music changes – Denver may be ground zero for an electronic music-based earthquake whose prenatal ripple effects can be found in virtually every corner of the music industry right now.

Pretty Lights has sold out Colorado’s Red Rocks amphitheatre (twice), performed at almost every major U.S. rock festival (including the holy trinity of Bonnaroo, Coachella and Lollapalooza) and has served more than one million downloads from his official website alone. His current popularity reflects similar trajectories of other major electronic producers such as Bassnectar, Skrillex and Girl Talk.

But while many rock fans may look at the exploding electronic dance music craze as something foreign, cut from a different cloth and appealing to a different demographic, Smith is revolutionizing the genre by – almost unbeknownst to himself – adopting techniques and philosophies first employed by rock bands like Phish and the Grateful Dead generations earlier. While Smith admittedly knows little about those bands, he shares more things in common with them than he does with many DJs in the electronic dance scene.

For one, Smith is not a DJ. He improvises live and, like Phish, his career owes a lot to emerging Internet cultures. He even embraced the ethos of the Dead’s tape-trading community when he decided to start issuing all of his music for free online. In fact, Smith has taken the notion of free music even further by establishing his own record label, Pretty Lights Music, which offers his and other acts studio releases for free.

“I haven’t really thought about the connection between the Grateful Dead and my own free music model,” Smith admits, when I suggest a similarity between Pretty Lights Music and the Dead’s tapers’ section. “They really started getting big in the ‘70s, right? That’s interesting. It’s the exact same thing.”

The Grateful Dead and the jambands that followed saw live taping as a way of spreading their music to new audiences, while simultaneously fostering a sense of community, loyalty and respect among their fans. Free music equaled free advertising. Smith sees it the same way, even if he arrived there on his own: he offered the first Pretty Lights album in 2006 as a free download because, frankly, nobody would’ve bought it. Nobody knew who Pretty Lights was when it was released and nobody cared.

“It started for me as the only possible way forward,” Smith says of his free music model. Knowing that he’d have to do something out of the ordinary to grab people’s attention, he used the predominant social media platform of the day – MySpace – to reach out to people personally, asking friends and friends of friends with similar interests to give his music a chance.

Prior to Pretty Lights, Smith had tried the more traditional route of making it in music, playing bass, flute and rapping in a group called Listen., which he describes as “the Beastie Boys meets Sound Tribe Sector Nine.” They did what all the bands they liked did before them – cut an album, toured and tried to peddle the CD on the road.

While this was a time before small, independent bands could put their music up on iTunes, they still attempted to sell the disc online using PayPal and shipping the product themselves. “It didn’t work,” says Smith. “No money was made. I was broke as hell.”

Conversely, with Pretty Lights, as soon as people started downloading the first album, Smith immediately began getting offers to play shows. From there, things took on a life of their own with a business model that made more sense than conventional wisdom whose modus operandi was to sacrifice album sales for ticket sales. (Especially if nobody’s buying albums, anyway.)

“When the second record came out, the 2008 double disc, Filling Up the City Skies, that’s when there had been sort of a critical mass – this perfect storm where the shows that I had played, the word of mouth, the new album and the new model all came together to explode and align. It literally went from 200 downloads a month to over 10,000 downloads a month,” says Smith, almost in disbelief himself. “And, thus, my touring career was born and I was able to play shows outside of my hometown.”

Even after Pretty Lights became a marquee act – selling out venues coast-to-coast and drawing headline-grabbing crowds at all sorts of festivals – Smith made the decision to keep his studio albums free because his original philosophy still works. Today, more than a million people have grabbed music from his website.

He also has chosen to keep his releases free because of something else, something unexpected: “It stopped being the only way I can get my music out there and it started becoming a new philosophy about music and why it’s created, about the relationship between the artist and the fan,” he says.

Alright, stop. He’s beginning to sound like a jamband. As it turns out, this just where the ideological similarities begin.

From the beginning, Pretty Lights – which Smith adopted as a moniker after seeing the phrase on a 1966 New Year’s Eve concert poster for Pink Floyd and The Who – put on a live show he hoped would create the kind of experience that people would want to come back to, again and again. Aware that watching a computer geek press buttons onstage isn’t the most thrilling thing to stare at for an entire evening, Smith decided that having a live drummer would help with the presentation.

At first, he enlisted his friend Cory Eberhard who he’d played music with for years. But then, things grew rapidly and Smith desired a drummer that was a little more suited for the larger production. So he hired Adam Deitch – an established musician from Brooklyn who was known for his hip-hop beats but who had also famously anchored a live incarnation of jazz guitarist John Scofield’s band, and was a member of new-generation funk staple Lettuce. Deitch’s first gig with Pretty Lights was at Red Rocks in the Summer of 2010. It was sold out. And the crowd went wild. So when Smith dropped Deitch from the live show this past spring, fans started talking.

“A lot of people wanted to assume the worst about why I left the band and they’re gravely mistaken,” Deitch explains. Shortly before deciding he wanted to go drummer-less, Smith signed Deitch’s own band, Break Science, to Pretty Lights Music and then, this past January, released their album. So, contrary to any rumor, Smith and Deitch are still great friends.

“There’s absolutely no animosity,” laughs Deitch, brushing off hearsay to the contrary. “[Derek] provided an opportunity for Break Science to reach a lot of people and, by being on his label, the next logical step would be to tour with Break Science. And I can’t tour with Break Science if I’m touring with Pretty Lights.”

Moreover – perhaps counterintuitively – Smith decided to stop touring with a drummer altogether for the same reason that fans might want to see a live musician up there in the first place: because he wanted to jam.

“I wanted to focus on the improvisation of the production, so I had to put a lot of energy into live communication to the drummer,” Smith explains. “We had an in-ear microphone setup so I could talk to him and tell him what was coming and make sure that he was always onboard. I’d be like, ‘Alright, I’m going to drop it out for a bar and a beat here, and we’re going to drop it back in there,’ and this and that. And a lot of my energy was going toward that.”

But, ultimately, Smith found it limiting. With just himself up there, he can feel free to take the music – and the live production – in any direction he wants to, at any time, without having to make sure his bandmate is still by his side. If he wants to add a break, an extra beat or drop the beat out entirely on a moment’s notice, then he can.

“He can do more stuff now within [the loop-based music sequencing program] Ableton, within his tracks, without having to worry about throwing me or somebody off,” says Deitch. “In a way, it freed him up creatively.”

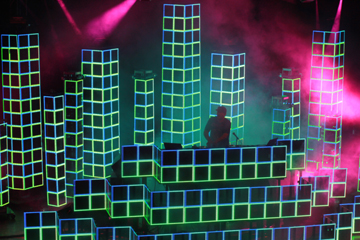

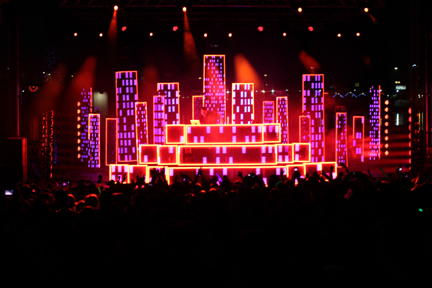

For now, Smith wants to “focus on the improvisational element of the production – focus [his] energies on reworking the songs live and manipulating the songs live,” as well as playing a different setlist each night. Smith also points out that he triggers a lot of the lights himself, including the video production for an elaborate backdrop that he calls the “LED City.” And he’s expanding the production exponentially with each tour, which means even more lights and lasers.

While the live show is his bread and butter, Smith has set his sights on a new project which, in conversation at least, he seems totally obsessed with. It is something that will resonate with fans of true live music and he knows it. While people have asked him for years about the possibility of touring with a full live band, Smith has become consumed with the idea of producing a record using only samples that he’s laid down on vinyl himself, from scratch.

To understand the significance of this, you must first understand how Smith achieves the “classic, Pretty Lights sound” that sets his music apart from the other fresh crop of superstar producers.

“My records that I’ve produced in the past have all been a combination of ‘sample collages’ and live instrumentation,” he explains. “Everything has had some live instruments in it and several samples from different pieces of music. I’ve never been a sample-based artist…it’s very important to me to create something new out of it. That’s where the word ‘collage’ comes in – that’s why I call it ‘sample collaging.’”

Unlike some DJs in the same scene as Pretty Lights or even his producer peers, the samples Smith uses are only one ingredient of something else entirely. Or they’re layered with so many new elements that even their key characteristics take on different flavors.

“In any given song, especially on my last EP series, there are going to be 10, 15, 20 different snippets and samples of vinyl from different genres, decades and parts of the world that I make work together,” Smith says. “That’s what brings the timbre that I want – as a musician – to the table; that’s what makes Pretty Lights’ music original.”

Central to his sound is a certain analog warmth that you can only find on old vinyl. Smith explains that he’s perfectly capable of picking up a guitar and faithfully covering a riff or recreating a certain chord progression, but while the notes and rhythms may be the same, the sound – the timbre – is vastly different than it is on the original recording. Those records are vintage stock – they may have sat in a basement for 30 years after being pressed in a plant in Michigan following their initial recording in a shady Detroit soul studio, before eventually finding their way to a flea market and, somehow, into Smith’s hands.

And all of that, both tangibly and intangibly, shapes the sound of the recording itself during playback. It affects the music. So, when Smith realized he wanted to make his next album “100 percent sample-free,” he realized he’d have to create those vintage sounds himself – not recreate.

To that end, Smith spent two weeks this past spring at Studio G in Brooklyn where he assembled a different lineup of musicians each day and, playing along with them (often on bass, sometimes on Wurlitzer, sometimes on something more exotic), Smith conducted sessions that have now been pressed onto vinyl and shipped back to Pretty Lights HQ where he’ll use them in place of traditional samples for his next album.

During the Brooklyn sessions, Deitch brought in some of his boys from Royal Family Records – namely, guitarist Eric Krasno and keyboardist/vocalist Nigel Hall – while other days saw Smith working with players from Dub Trio, The Budos Band and a revolving cast of others. While isn’t a set release date for the album yet and Smith plans to release other new Pretty Lights music in the meantime, this one is his baby.

“I plan on searching the world for vocalists and street musicians and other elements and I’m writing lyrics,” Smith says, excitedly. “Whether it’s some dude on the street in Barcelona or some guy in a bar in New Orleans, that’s the path I’m taking.”

It’s a path that will take Pretty Lights well into 2012 and beyond. As for this year, Pretty Lights has a solid fall tour booked after slaying it once again on the festival circuit this summer.

It’s July at Camp Bisco – a festival centered around the live improvisational-based rock music of the Disco Biscuits, which is now its in it tenth year – and Pretty Lights is headlinig the dance tent. The crowd spills out past campsites and RVs in every direction, all the way to the tree-line. When Smith finally arrives backstage at 1:30 a.m. via golf cart, there’s a swarm around him with a buzz usually reserved for rock stars, but not usually seen in this kind of music scene – or at music festivals, where everyone backstage is a performing musician or standing near to one.

Standing 6’8" and wearing a nondescript blue hoodie that somehow draws attention to himself despite intentions to the contrary, Smith cordially says hello to friends and acquaintances who have descended on his golf cart as it pulls up.

He eventually takes a stroll to the stage to check out the equipment that he’s working with before disappearing into his trailer for some alone time where, according to him, he chills out with his girlfriend, maybe tosses back a shot, maybe pulls a quick puff, gathers his thoughts and hits the stage before greeting thousands of kids obsessed with the beat. His beat.

The mode of the music has changed and while the walls of Denver might not be literally shaking just yet, you can feel the aftershocks all the way up here at Camp Bisco’s day parking lots where kids have come from miles around just to dance and party to Pretty Lights.

It’s a sight that you’d better get used to because the future’s here and Derek Vincent Smith has the soundtrack ready.