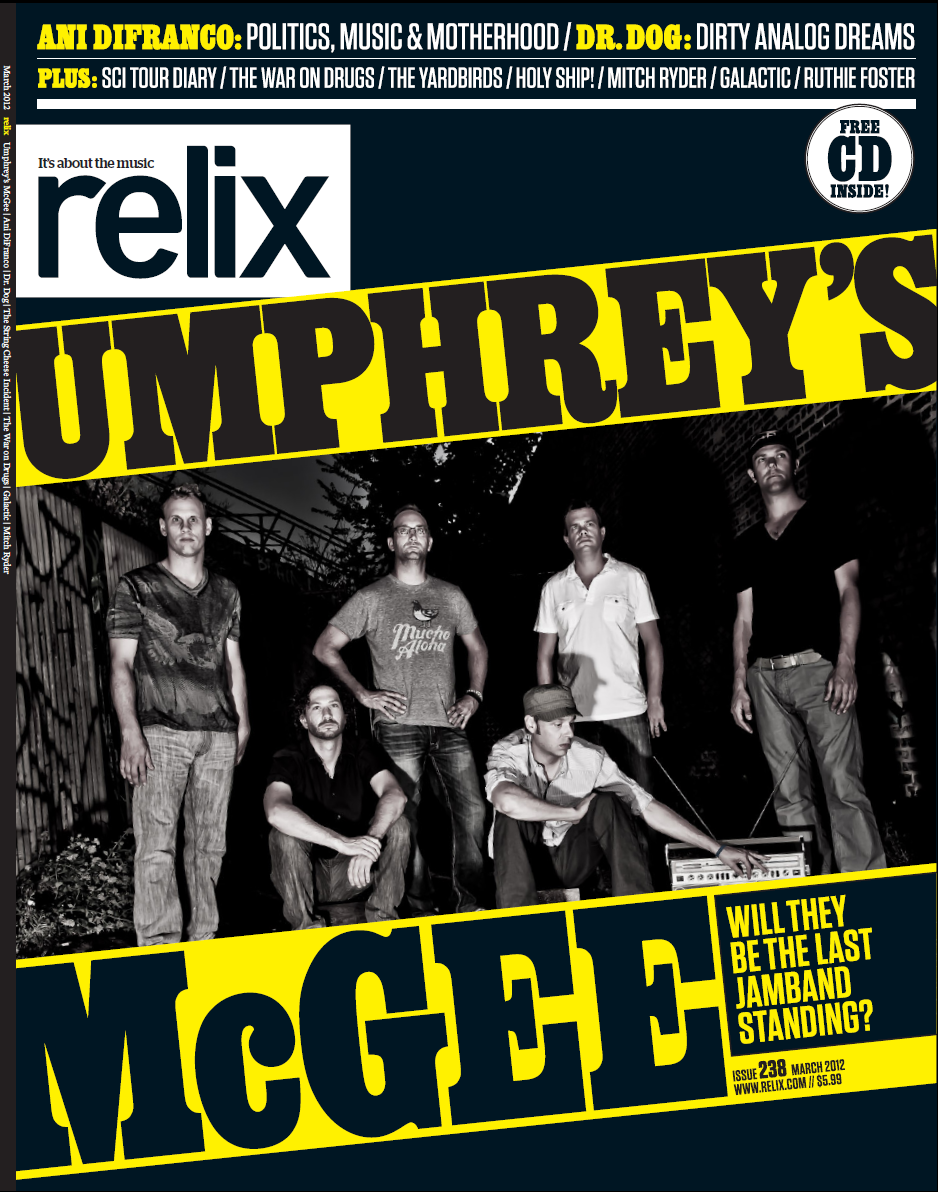

On the Cover: Will Umphrey’s McGee Be the Last Jamband Standing?

The following is an excerpt of the Umphrey’s McGee cover story featured in the March 2012 issue of Relix. To read the rest of this cover story, pick up a copy of the issue when it hits stands on February 28 or order one directly from us online.

Be sure to check back each day until the issue hits stands for a new piece of Relix exclusive Umphrey’s content including unreleased video, signed memorabilia and more!

Umphrey’s could also be the last “classic” jamband standing. Think about it: What group of intrepid twentysomethings is waiting in the wings, guitars aimed for bear? With other bands taking breaks, breaking up or merely breaking musical wind, it’s easy to regard Umphrey’s as the final hurrah of a great American musical tradition forged in the Haight-Ashbury crucible nigh on fifty years ago.

Umphrey’s may be firing on all cylinders, yet significant personal and business-related changes are afoot. As the band files into Vintage Vinyl, former sound engineer Kevin Browning greets them, beaming happily as he holds his own six-month-old daughter, Murphy. Last February, Browning jumped off the road after 13 years. He now works out of the band’s Chicago offices, devoting himself exclusively to the marketing, business-development ideas and special events that were beginning to overwhelm his plate.

“I’m not built to be on the road,” Browning tells me later. “I’m not a road dog or a 30-year guy. I’ve loved every minute of it, but it’s something I needed to do for me and for the band, to help us get to the next level.”

Browning admits that there might have been a wee bit of resentment from other band members when he announced his decision. He was, after all, the first crew member to join guitarist Brendan Bayliss, bassist Ryan Stasik, keyboardist Joel Cummins and drummer Mike Mirro, who formed the original Umphrey’s lineup at the University of Notre Dame in late 1997 – with percussionist Andy Farag added the following year. Chris Mitchell – an extremely pierced and tattooed former Navy engineer, whose laptop “family picture” portrays a pair of gorgeous Ducati motorcycles, at his wife’s suggestion – replaced Browing at the soundboard.

“I thought it would be really weird,” says Bayliss of Browning’s career move. “Now, it’s totally cool. Chris Mitchell is a pimp, and a joy to be around. But, initially, I felt like we’d failed. Why didn’t the initial thing work? When you’re around somebody for 11 years and they’re like, ‘Uh, I’m going home,’ you wonder what went wrong? I’m not going home.”

That’s classic Bayliss, by the way. The occasionally tortured Irish-American songwriter oscillates between endearing sentimentality and caustic truth-telling – and not just in his lyrics. And his feelings on this particular subject might well change after his own child is born around the Fourth of July.

A month earlier, Umphrey’s other lead guitarist, Jake Cinninger, who joined the quintet in 2000, is expecting his second child, scheduled for delivery the same weekend Umphrey’s is slated to make its sixth Bonnaroo appearance. The gig is important and symbolic enough for the group to fulfill even if Cinninger has to helicopter in for it from his home in South Bend, Ind. Umphrey’s McGee was one of the very first bands to perform at the very first Bonnaroo in 2002, and its 2004 late-night appearance, which is still recalled with some measure of awe, indisputably raised the band’s reputation up a notch.

Cummins, Farag, Stasik and Bayliss have all put a ring on it within the past two years (Bayliss for the second time). This leaves only drummer Kris Myers, who replaced Mike Mirro in 2002, to provide his friends with vicarious adventures in singlehood. The band’s collective dive into domesticity has led to some geographic reorientation as well. While Cinninger has lived in South Bend for several years, the rest of Umphrey’s have been based in Chicago. But Cummins moved to Venice Beach, Calif., and Farag moved to Charleston, S.C., in recent months, and Stasik is considering a similar southern relocation, so the band will need to make some adjustments.

“There’s more to life than just driving around and being in a rock group,” says Bayliss. “So in order to make the band work, we have to learn to make our families work. And honestly, a lot of it just has to do with our wives’ biological clocks.”

“I get a lot more sleep now,” says Stasik, who, like the rest of the band, is squarely in his mid-thirties. “When you only have two single guys out of 12 on the bus, you don’t have as many dance parties going on in the back room,” he notes. (The band’s lighting designer, Jefferson Waful, is the other single dude.) “Those days are gone.”

“Our backstage atmosphere is not even close to the partying rock-star cliché,” Farag adds, although he makes exceptions for New York and a few other hot spots. “I’d say 85 percent of the time it’s us backstage wondering ‘When do we go back on?’ It’s probably not as exciting as people might think.”

Whatever Umphrey’s McGee is lacking in rock and roll Gomorrah, they’re more than compensating for it musically. Each of the three shows that the band plays in St. Louis explodes in a different manner. They play some of the most densely composed rock around, changing keys and time signatures with head-spinning finesse. Their “Jazz Odyssey” and “Jimmy Stewart” improvisations – more or less interchangeable titles at this point – can go in any direction whatsoever. And they drop rehearsed or spontaneous covers like bonbons of the gods.

Once known as the band that rehearsed more than any other, Umphrey’s is now a smoothly oiled Transformer of a group, caroming effortlessly between head-banging rawk, syncopated adventures and four-on-the-floor dance grooves.

Umphrey’s unique collective identity was personified most strongly, perhaps, during the second set on December 29. Several minutes into “1348,” Stasik called an off-setlist option for “Dr. Feelgood” into the band’s in-ear monitors. The group switched gears abruptly, diving into the Mötley Crüe hit for a couple of minutes before, just as suddenly – like a small flock of geese in tight formation – returning to the setlist with “Cemetery Walk II.” From the hair-rocking ridiculous to the sublime, John Coltrane’s transcendent “A Love Supreme” bubbled up out of the middle of this mesmerizing instrumental house-beat epilogue to “Cemetery Walk,” the urgent, anxious rocker that followed the show opener “Jazz Odyssey.” As a topper, the group next debuted a new cover of TV on the Radio’s “Second Song.”