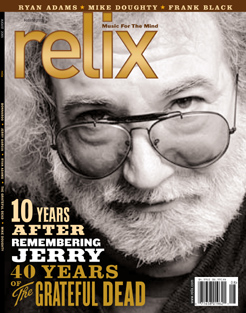

My Jerry (Dennis McNally Remembers Jerry Garcia)

Here’s a wonderful piece from our August 2005 issue, which focused on the Grateful Dead, 10 years after Jerry Garcia’s death. Here longtime Grateful Dead publicist and the group’s official biographer, Dennis McNally shares some memories…

Just before he was about to walk my bride-to-be, Susana Millman, down the aisle – hey, the officiating “minister” was Wavy Gravy, so it wasn’t exactly a formal affair – Jerry Garcia was extremely fidgety. One of the bridesmaids asked him what the matter was. “I’m nervous, man.” “But Jer, you play in front of 50,000 people,” she replied, shocked. “Yeah,” he grinned, “but I don’t have my axe now.”

Well, he did fine, although it’s true that he and Susana set a land speed record for covering the ground. The point was, Jerry Garcia was a very human guy. He’d put himself in the father-of-the-bride position by acting as our matchmaker, telling both Susana and I that we should check each other out, a move straight out of seventh grade, but it worked. And since Susana’s dad was long gone, he was happy to serve.

Very human. All of us – band, crew, Dead Heads – watched and suffered as he tried to erase his pain in the last years, and a good portion of that pain was the direct result of his fame, of the expectations life had put on him. Fifty people and their families needed him to work so that they could pay bills. A million people needed him and his band to supply their musical fix about 80 nights a year. And at heart Jerry wanted to be Huck Finn, or more precisely an 18-year-old guy gettin’ stoned, playing music, flirting with girls, and having fun. That side came out when he talked about his past – fragments from his boyhood and youth that had molded him, and that were far away from being a star in the 1990s.

One of the few times I ever saw him even a little bit flustered was when I was able to introduce him to one of his heroes, a man named Lucien Carr, who’d been a close friend of Jack Kerouac, one of Jerry’s fundamental cultural icons. Reading On the Road had been a life changing experience for Jerry – so much so that when he read my book about Kerouac and liked it and learned I was a Dead Head, it was enough for him to invite me to be the Dead’s biographer, too.

Lucien had killed a man, served his time, and become a newspaper editor afterward, but as a result he cherished his privacy more than say, Allen Ginsberg or William Burroughs. He’d become my mentor in many ways, and I’d gotten him to come to a Dead show in Washington, D.C. When I told Jerry he was there, Jerry reacted most uncharacteristically. A little taken aback, Garcia dithered with an attack of shyness, and then went out and said hello with the remark, “Ah, the real Roland Major,” the pseudonym Kerouac had given Lucien in a book. Jerry had other business at that point, but he made sure to catch up with Lucien and shake hands before the end of the day.

Real heroes like Lucien could make him blink, but not the merely famous or powerful. In March 1993, the tour came to D.C. again, and this time there were Democrats in the White House. Vice President Gore’s Director of Advance, Dennis Alpert, was a Dead Head, and I got a call. “Hey, it’s our house now. Wanna come over?” Most of the band went over, and we admired the White House and then hung with both the Vice President and later Mrs. Gore for a while. But the striking memory I have is of Jerry and V.P. Gore in the Oval Office.

President Clinton was gone that day, but the Veep gave us a special tour of his office, and spent some time on the President’s desk, which had been John Kennedy’s and which almost anyone of our age recalled from famous Life magazine photos of JFK’s son John-John playing under it. In sweat pants and a particularly grubby shirt, Jerry looked like an unmade bed, and Gore looked, well, like a Vice President, impeccable. The sweet thing, I realized, was that neither of them gave a shit about each other’s appearance; they were both enjoying the conversation.

Jerry’s heroes weren’t all hip literary types, or even musicians. He was a San Franciscan, and although he was never a big-time sports fan, he followed the 49ers and Giants like so many of his fellow citizens. One Sunday afternoon the 49ers were playing the – I think it was the NY Giants. This was during the Joe Montana – Jerry Rice era, but they had a bad day, and were down 3 points with seconds to go. On the last play of the game, Joe throws to Jerry, who runs about 70 yards for a touchdown; 49ers win.

I cheer, and go downstairs to the van for a ride to that night’s gig. As usual, Jerry came down to the early van, but while he could sometimes be quiet, this time it was obvious he was visibly seething. Finally I asked him if he’d seen the final play of the game. “Naah, I got so pissed I turned off the TV.” When I explained what had happened, he immediately cheered up and, as I recall, played a ripshit show that night.

Our most elaborate sports experience, though, was with the SF Giants baseball team. It was 1993, and the Giants had come within a day or two of being sold and moved to Tampa Bay. One of our production guys, Eric Colby, was a maniacal Giants fan, and he passed on to the band an invitation to sing the national anthem on opening day. Now, every music act in history has sung the national anthem – like benefits, it just goes with the territory of being performers. But not the Dead. Ever. Twenty years before they’d talked about doing “Stars and Stripes Forever” at half time of a 49er game, but it hadn’t panned out.

Weir says yes. Like I say, Jerry’s not a serious baseball fan, but this is after all kind of a big moment in SF sports history. “OK, man, I’m in.” Vince Welnick draws up an arrangement – he described it as “Straight Sons of the Pioneers” – and off we go. Somehow, I’ve been elected road manager for the day. We all know that a) the “Star Spangled Banner” has ruined a lot of singers, and b) the Dead are not going to make the rock and roll hall of fame on their harmony singing. And when I call Jerry and suggest a rehearsal, he snaps, “I know the song, man.”

Finally I get a half-bright idea. I call Vince, and tell him to call Jerry and say that he’s freaking and wants to rehearse. Well, an appeal from another musician is not something Jerry can dismiss. I also suspect that he didn’t want to look bad in front of the hometown folks. Anyway, they put in about three hours on the hardest two-minute song ever.

The complication was that the game was at 1pm, and sound check was at 10am – and traffic being what it was, they couldn’t leave the stadium. So for nearly three hours, I had to try, mightily, to entertain them. At first it was easy, because the other singing act that day was Tony Bennett. I think one of Tony’s kids was a Dead Head, and I know that I’ve seen him at least once at a show, where he visited with Jerry, so they chatted about this and that. After a while, though, Tony slid off, and things got boring.

At some point I turned and saw three legends of SF baseball passing by – Willie McCovey, Gaylord Perry, and Willie Mays. Well, I turn into the introductions king, which works out fine – for a while. It turns out that Perry was Bob Weir’s favorite player, and they get to talking. And Willie McCovey is one of the planet’s gentlemen, and although I strongly doubt he has more than a very vague idea who Jerry is, he’s more than happy to socialize, so that’s cool.

Finally, I go up to Willie Mays, who’s sitting in a golf cart and, it turns out, is impatient to get to the team alumni gathering. “Mr. Mays, could I introduce you to Jerry Garcia, who’s going to sing the national anthem today?” “No,” he barked, and then yelled at Willie and Gaylord, “Come on, I want to get out of here.”

But what you have to dig about Jerry is that after sitting there and simply glowing about shaking Willie McCovey’s hand, Jerry spent five minutes laughing helplessly about how he’d been snubbed by Mays. Of course it wasn’t personal, because Willie Mays was a notoriously grumpy guy, but the truth was that Jerry genuinely enjoyed the idea of being treated like an ordinary person – it just didn’t happen often enough.

My job got a little easier when the Giants’ p.r. person came to ask us to do a press conference. I took the guys to the Giants’ dugout, and a gaggle of press and photographers clustered around them, firing questions. I was slightly startled when I noticed that an attractive woman, who I realized was a well-known local politician named Angela Alioto, had not only slid into the press conference (God, politicians like the spotlight!) but had her hand on Garcia’s leg, but he seemed to be bearing up. When they asked him why the Dead had achieved some kind of status in the city, he said something like, “It’s like bad architecture and old whores – after a while, seniority gets you respect.”

And if you’re wondering, the boys went out and freakin’ pinned the anthem.

As I said, in his last years Jerry battled a lot of demons, and he battled them by using drugs to insulate himself from feeling them. Since at the same time he was doing that he was not dealing with things like raging diabetes, he was experiencing fairly serious mood swings. It wasn’t as though he was rampaging around yelling at people – he was usually too civilized for that – but he was grumpy and moody and posting big “leave me alone” signs with his body language.

So I left him alone. As far as doing press went, Jerry had a professional attitude. He felt that part of his job with the Dead was communicating with Dead Heads via the media – we didn’t have a website yet – but if he’d never had to do another interview, he’d have been happy. But he was the best of all bosses. He trusted me to recognize if something was necessary or even potentially interesting or cool, and then he’d do it. So when he got profoundly unhappy – pretty much from 1993 on – I let him be, either steering stuff to other band members or just saying “No” as nicely as possible.

There was one interview in his last years that I knew was worth asking about. One day I got a call from the American Movie Channel, AMC, about a show they did called “The Movie That Changed My Life,” or something like that. Well, Jerry had been a film nut since he was a kid. I’d found the silent 8 mm home movies he’d shot around 1963 during my research (one of them was a cartoon made by shooting stop action on a chalkboard that was clever and quite funny) in the early 1980s. He’d made the Grateful Dead Movie, of course, and I’d talked with a lot of people about that. And then I’d watched him and Len Del’Amicco have a lot more fun using video and computers rather than real film and razor blades to edit So Far.

So when I got the call, I figured it was something he’d enjoy. I hadn’t pitched an interview to him in months, but I braced him before a Garcia Band show at the Warfield one night and told him about the idea. Boy, was I right. He proceeded to do the interview with me right there, going on for 20 minutes about the first movie that had grabbed him – Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. It had scared him so silly that he could still remember the pattern of the fabric on the seat in front of his that he stared at when he couldn’t watch the screen, and consequently hooked him on both movies in general and horror movies (and other manifestations of horror) in particular. I certainly can’t remember what interview was the last one I arranged for him, but I’m pretty sure that was the last one he really, really enjoyed doing.

In addition to being human and generally a lot more normal than Dead Head folklore might necessarily acknowledge, Jerry was… Jerry. Which is to say incredibly erudite, thoughtful, funny, and wise. Off the stage, one of the times I was most impressed with him was when he met the celebrated lyricist Mitchell Parish, the man who’d written “Stardust,” “Stars Fell On Alabama,” “Sophisticated Lady,” and “Moonlight Serenade” – the real deal. We were at Madison Square Garden with the Jerry Garcia Band. Steve Parish, Jerry’s long-time roadie and the manager of the JGB, was a cousin of Mitchell’s, and invited him to the show. Mitchell was 90, and his knees were shot so he was in a wheelchair, but he was sharp as hell and definitely ready to rap.

Well, he met his match that day. He and Jerry started raving about old songs – songs that Parish or people he knew had written – and Jerry matched him tune for tune. Not an ego thing, just two amazingly knowledgeable music historians (one with the advantage of having lived through the era!) swapping stories. The room was so packed that the Vice President of Arista, in a $2,000 suit, was sitting on the floor – but it was quiet, as everybody just listened to this amazing conversation. Parish started one sentence with, "When I wrote the songs for the Marx Brother’s “Coconuts” in 1928," and you knew he wasn’t b.s.ing. And obscure as it got, Jerry was there, jamming on the rap the way he did on his axe.

Game to the end.