Gregg Allman: The Other Side of This Life (From The Archives)

This piece originally ran in the January_February 2011 issue of Relix.

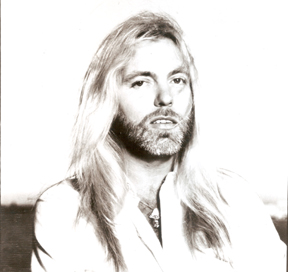

Photo by Danny Clinch

When Gregg Allman was a young man, his restless soul led him into terrain that tested his limits. Pursued by demons while searching for angels, he never dwelled on the ground he stood on. His writing reflected his spiritual aspirations, so aptly expressed in the transcendent vision of “Dreams,” an Allman Brothers Band anthem and one of the greatest rock songs ever written.

The young Gregg had a voice that crackled with emotional wisdom, an instrument seemingly honed during many lifetimes. At a time when almost all white rockers attempted to sing the blues as if they were trying to put on an ill-fitting suit, Gregg sang with a voice that expressed infinite sadness and unimaginable pain. He was a phenomenal white blues singer – a budding artist whose imagination produced the tortured cry of “Whipping Post,” the anguish of “It’s Not My Cross to Bear” and “Black Hearted Woman,” and the lonely fugitive blues of “Midnight Rider.” Along with his brother Duane, and his great genre-defying band, Gregg interpreted the work of the blues masters with a finesse that only his most inspired contemporaries could match.

Now, Gregg is an aging man who’s packed multiple lifetimes of experience into his 63 years. After years of battling hepatitis C, he received a liver transplant last summer and has slowly made his way through a difficult convalescence.

“Oh, shit. I never knew that a pain like that existed,” he says from his home in Georgia a few days before returning to the road for the first time since the operation. “I’ve been to the pinnacle of pain. I’ve had enough pain to last me the rest of my life – just from the operation itself.”

Gregg has become one of those wizened bluesmen that he emulated so many decades ago. His new album, Low Country Blues, is an extraordinary exercise in blues singing. On the record, which was cut last year before his liver transplant, Gregg inhabits songs culled from the mythological depths of the genre’s canon, including his own laconic comment on life, “Just Another Rider.” His voice is like blues elder – several of the men who originally sang these songs died before they reached his age.

The hard living is now behind Gregg. He has now been sober for 14 years after a hectic 30 years of heavily indulging in narcotic drugs and alcohol that would have killed most people. In 2009, he stopped smoking marijuana, a decision that he credits with improving his voice to a point where his singing on Low Country Blues may be – by his own account – the best vocal performance of his life.

The record was Gregg’s first experience with producer T-Bone Burnett after a lifetime of recording with the late studio mastermind Tom Dowd.

“Mr. T-Bone is an incredible man,” says Gregg. “I tell you I was sweatin’ it. When it came around time to record again, I thought, ‘Man, what are we gonna do without Tommy Dowd?’ We were just coming off the road and my manager said, ‘I want you to stop in Memphis and meet this guy.’ I made up my mind about T-Bone when I got to Memphis and he was there with some architects measuring the Sun Records building board for board because he was going to build an exact replica of it. I thought, ‘Anybody who would go to such lengths must have something going for him.’”

The two hit it off as soon as T-Bone told Gregg how much he respected Dowd. They began talking about listening to the blues on Nashville radio station WLAC when they were younger and decided to make a record concentrating on those old blues songs. Burnett had a hard drive with about a thousand blues ‘78s on it. He picked out 20 of them and sent them to Gregg for consideration.

“You could hear the crackling and the scratches on them,” says Gregg. “Some were obscure, some of them I had never heard before. He told me to pick 15 that I wouldn’t mind recording.”

Despite the positive first impression, the project almost broke down before it got out of the showroom.

“After I got to know T-Bone a little bit and we got comfortable,” says Gregg, “they told me T-Bone wants you to come to Los Angeles to record. And he wants to use his own band.” He pauses for emphasis. “I thought, ‘Well, this thing’s over before it starts because I’ve got a hell of a band already.’ And then I thought back to when I first worked with Tommy Dowd. We had Capricorn’s studio right there in Macon but he wanted us to come to Criteria in Miami, in the dead of summer, hotter than hell. I didn’t want to do it. And my brother said, ‘We’re goin’. It’s his sandbox. If he wants us to play in his sandbox, we’re gonna play in it.’ Good thing he didn’t ask us to play with another band,” Gregg exclaims, laughing.

Gregg in 1987

Allaying Gregg’s fears further was the discovery that the band for the session included Dr. John on piano and Doyle Bramhall II on guitar. Both play brilliantly in a tight, well-focused backing group that offers terse, powerful accompaniment to Gregg’s vocal, guitar and Hammond B-3 organ work.

“We did ‘Please Accept My Love’ in a version that was listed as B.B. King’s but it was a Texas blues arrangement,” remembers Gregg. “Dr. John was in there and he says, ‘This ain’t B.B. King, it’s T-Bone Walker.’ So we were trying it out and I said through the microphone to T-Bone, ‘OK, you wanna take a crack at this?’ And he says, ‘It’s OK we already got it!’ [Laughs.] I said, ‘No man, we just ran that down.’ So we tried it again but he was right – we had it before we knew it. One take. “It’s been a long time since we played together,” says Gregg of Dr. John. “It’s such a pleasure playing with him again. He played on my second record [1977’s Playin’ Up a Storm ], but back then, even though we were friends, we couldn’t really enjoy each other’s company because we were both so strung out.”

One of the highlights of the record is a big band arrangement of “Blind Man,” a staple for Bobby “Blue” Bland but also for Gregg’s favorite vocalist, Little Milton. “It was all cut live – the whole damn thing, horns and all,” says Gregg. “There’s no count off to that song. It has big band feel to it. I’ve always wanted to do that. Not so much live, but in the studio. Bobby Bland would use a huge band sometimes. Little Milton killed that more than anybody.”

Gregg becomes animated as he recalls Little Milton’s guest appearance at The Allman Brothers Band annual run at the Beacon Theatre in 2005. “He came and played with us and the next thing you know the man’s gone,” he says, still sounding wounded. “Every song he did, he would stand back with his head raised like he’s in church and the microphone would be at a full arm’s length. Man, he could deliver it.”

As they were selecting material for the record, a particular song caught Gregg’s attention: a chilling Sleepy John Estes tune called “Floating Bridge.” The episodic tale of a drowning told from the perspective of the victim had an eerie, dreamlike quality that fascinated the singer. “I wasn’t familiar with it, but it stood out,” he recalls. “I carefully listened to the lyrics and we changed them a little bit.” Gregg sings the song in a high, reedy voice, fragile and otherworldly. It’s the voice of a man who’s faced death.

“Wait ‘til you see the cover,” he says of Low Country Blues. “The cover looks like it came from that song. It’s about death. Being an addict, I had many brushes with death. Because they’re self administered, they make you feel,” he pauses, “like such a fool. “It’s very scary when you wake up,” he trails off, this time pausing longer. “We won’t go there. If you listen to the whole record there’s another song, ‘I Believe I’ll Go Back Home,’ that also touches on that. It was a very emotional recording session.”

On the record, Gregg sings “Floating Bridge” with powerful, full-throated emotion, a dramatic contrast to the plaintive country blues singing he uses when accompanying himself with guitar. His facility with such a wide range of vocal styles is the result of his ability to inhabit the material he sings about rather than just copy it. Gregg is inside every song on Low Country Blues.

“That’s exactly what it feels like,” he says. “I always felt like that even when I was a kid. I’d hear a song or see a movie and I would live it. It felt like it was going right through me.”

Indeed, the emotions Gregg plumbs on Low Country Blues are the product of his life experiences. He agrees that he probably couldn’t have sung these songs as well if he were a younger man.

“I think it includes the wisdom of growing older,” he says, reflecting on the album’s general tenor. “I could have made a reasonable facsimile at best when I was younger. The notes might have been in the right places, but it wouldn’t have been [what Low Country Blues sounds like]. You learn about it as you grow older – just like everything else. “I wonder how I would have done this back in ‘69. Why didn’t I do this right out of the box, ya know? It’s like being an architect. You get better at what you’re doing. You learn by doing. Just like a record producer. The more you do the better you get.”

Photo by Danny Clinch

Most of the songs on Low Country Blues deal with courting and losing women, experiences Gregg is well versed in after being married and divorced so many times in his life.

“I guess I just wasn’t meant to be with one woman,” he says with a shrug. “But I’ll always keep trying.”

During the course of the conversation, Gregg recalls his early inspirations – many sang about broken hearts, fractured relationships and missed opportunities. These were artists such as B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker that he heard as a kid on WLAC, the radio station out of Tennessee that came on at night and played blues. When he started out playing music, he says that singing was the last thing he wanted to do – he played guitar – but that the choice between a job doing manual labor or music forced him into it. Soon after, he discovered singing’s pure emotional quality.

“To change the tone of an instrument, you have to do something physically,” Gregg says. “A whole lot of emotion goes into playing but singing, it’s actually part of your body. It comes to you right off the brain; it doesn’t have to go through an instrument to come out.”

He does, however, remember the impact of hearing one particular instrumentalist early on – the jazz organist Jimmy Smith. “For years, I fantasized playing a Hammond like he did,” he says. “I didn’t actually see Jimmy Smith until right before he died. He was 76 years old. I went to see him one night in New York City and it was something else, man. His hands were a little slow, but his feet hadn’t slowed a bit. All he needed was a drummer and his feet. He played more shit on them pedals than anybody. I couldn’t believe it. And he had this Hammond organ with two Leslie cabinets that rotated at different speeds. And he had this I-don’t-give-a-shit attitude. Somebody called out for ‘Back at the Chicken Shack’ – one of those burners – and he said, ‘Goddamn! Ease up on that. I’m 76 years old,’” Gregg laughs.

As he’s gotten older, Gregg has gotten a chance to build relationships with his children. A couple of them have even followed him into the world of music making.

“My daughter Layla has a new record out with her band Picture Me Broken,” he says with a smile. “My son Devon’s band, Honeytribe, is killer. He’s a great kid. As a matter of fact, he’s gonna be on my next tour. We’re in the kind of business where we’re always at opposite ends of the world. That’s a drag but lately we’ve been spending Christmas at my house. I try to get all [the kids] there, you know? It’s a very special time for me.”

During Christmas 2009, Gregg’s battles with hepatitis C grew increasingly taxing. “I had what you call a chemoembolization,” he says of one particular treatment. “They put a rubber band around a portion of your liver – the portion that had three cancerous tumors in it – and that cuts off the blood supply and it kills it. Believe it or not, [the liver] grows back. Then they give you chemotherapy. It makes you kind of sore all over. I was a pretty sick boy by the time Christmas rolled around. But they all came over, everybody – and my mother was there, too.”

While Gregg began treatment for hepatitis in 2007, the chronic damage to his liver led doctors to recommend a transplant. Completed in June 2010, the operation has been a complete success. “The doctor told me, ‘That liver loves you,’” he chuckles.

With all he’s been through, Gregg has not lost his thirst for life. While he endured the painful recovery from the liver transplant, he was heartened by his growing relationship with his children and the knowledge that he had a great record in the can – a project he could look forward to bringing to the world after he got healthy again. The transplant has also given the iconic musician a newfound spirituality to draw strength from.

“After I got out of the hospital, I had to stay in the Jacksonville Beach area for five weeks in case something went seriously wrong,” he says. “I stayed at this place – it’s like a resort – and my room was right on the beach. You could walk out of your room and walk to the water. On quite a few mornings, I watched the sun rise. It was beautiful. It puts you at peace.”