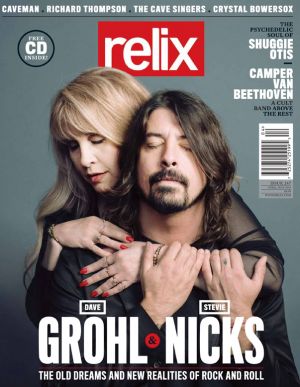

Dave Grohl & Stevie Nicks: The Old Dreams and New Realities of Rock and Roll

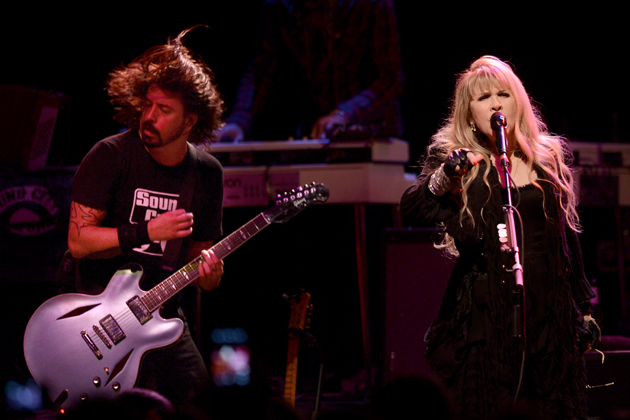

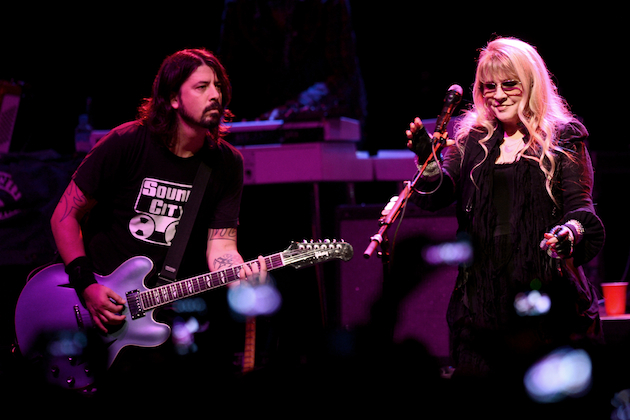

A quarter after 11 on a Wednesday night in New York City, Stevie Nicks appears onstage at the Hammerstein Ballroom before a sold-out crowd. She’s clad in various layers of black and sports a pair of sunglasses and fingerless gloves. The band behind her throttles into “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around,” the song she cut with Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers in 1981 for her solo debut Bella Donna. After the sinewy guitar figure and the first verse, a voice joins her for the bridge. It’s not Petty or her longtime Fleetwood Mac companion Lindsey Buckingham. On this evening, it’s her new musical beau—Dave Grohl.

The five-song set is the last of a star-studded evening billed as The Sound City Players with John Fogerty, Rick Springfield, Rick Nielsen of Cheap Trick and Lee Ving of Fear backed by Grohl’s band the Foo Fighters and auxiliary musicians, including Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic. The assembled troupe debuted during the Sundance Film Festival in Utah the previous month before storming into the Hollywood Palladium Theater a few weeks later. After New York, the show will travel to London (minus some members) before being reprised—potentially for the final time—at the South by Southwest Music Conference in Austin, where Grohl also happens to be delivering the keynote address.

The shows are in conjunction with Grohl’s documentary Sound City about the legendary, LA-based recording studio that birthed such albums as Fleetwood Mac, After the Gold Rush, Damn The Torpedoes, Terrapin Station, Nevermind, Blind Melon and Rage Against the Machine, among many others. They’re also anticipating a record of original material, Real To Reel, which came out of the film and features many of the show’s guests.

As the clock edges toward midnight, the band is at full-tilt on the show-closing “Gold Dust Woman.” This 10-minute, fuzzed-out, feedback-laden take is twice as long as the original studio version. Though there’s always been an inherent tension to it, with three guitars in the mix and Taylor Hawkins of the Foo Fighters pounding heartily on the skins, there’s now a chunky bombast that makes it anew. This isn’t shtick or nostalgia—this is new territory for the song. The crowd hoots and hollers with approval. Though two decades separate Nicks from her band-mates, you couldn’t hear a generational gap in the music.

The next day, Valentine’s Day, Nicks and the band perform her new song “You Can’t Fix This” from the film and album on Late Show with David Letterman. After the taping, Nicks and Grohl head 20 or so blocks south where they’ve agreed to sit for a conversation to discuss the state of rock and roll.

For reference, Fleetwood Mac have sold more than 30 million albums in the United States alone. Nicks’ solo records are nearing 10 million. The Foo Fighters have moved more than six million domestically while Nirvana, which Grohl served as drummer for from 1990-1994, have more than 15 million to their name in the U.S.

Both bands routinely sell out arenas across the country and you’d be hard pressed to listen to the radio and not hear their songs several times a day. Despite such massive success, Grohl and Nicks remain grounded and humble about their craft and careers which make them ideal participants for such a conversation.

Grohl arrives first, dressed in a long sleeve, blue and black plaid button-down with faded blue jeans and black Doc Martens. Nicks arrives a short while later, again in black, and retreats to freshen up before the photo shoot. When the shoot begins, there’s a palpable affection on display as they find themselves in the continued honeymoon phase of newfound friendship.

After the shoot, the two settle into a nearby couch to discuss making music in the digital age, the death of radio and the journey of making your dreams a reality.

Dave, in your film Sound City, you talk about Nirvana heading down to LA to record Nevermind and the idea that the three of you left everything behind. You say, “When you’re young, you’re not afraid of what comes next—you’re excited by it.” Stevie, when you read the letter you wrote to your parents in 1973 in the film, you talk about that idea of not knowing what was coming next but having faith in your dreams. At what point does that change? When do you become afraid of the future versus excited by it?

Dave Grohl: I’ve never been afraid of the future.

Stevie Nicks: Me either. I’m always excited about the musical future.

Dave: It’s great to look back on all these things and be proud of your achievements, but I still think that there are better albums to be made and more songs to be written. As you get older, you evolve in a way—you can appreciate things more—and you hone your craft or understanding of music more so that it becomes deeper, richer and fuller.

Stevie: Look what we just did last night. [She’s referring to the Sound City Players show the night before at Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City this past February.] We rehearsed one day at [Dave’s] studio, just those five songs, not to mention the rest of the fantastic show. There’s never been a “Gold Dust Woman” like that, ever.

That’s what you said when we spoke earlier, that it was it was perhaps the greatest version you’d ever experienced.

Stevie: I will never see that song the same again. Here I am at 64 years old, going, “I’m onstage with this amazing group of men that are playing this song that’s been played since I wrote it in 1976, and it’s spectacular and it’s brand new.” [There’s] excitement for all of us to be up there on that stage and not really wanting it to end. I have a Fleetwood Mac tour that’s going on for a year. It’s going to be great, everybody’s in good shape, everybody’s happy, everybody’s excited, and I’m excited about it. But I’m already beyond that [in my head]. That’s why I never got married—that’s why I never had kids—because I wanted to be able to follow my muse and go wherever I wanted and do whatever I wanted. There’s always a new, cool thing out there waiting and it makes me understand that there’s definitely a god, powers, somebody or a house of spirits that are throwing out those ideas to us. People like me, Dave Grohl and Taylor [Hawkins] and all those great men on that stage, we’re just catching them. We’re like dreamcatchers. Most people really aren’t like us.

Dave: It’s funny, the introduction of the movie, where i say, “We were just kids, nothing to lose, nowhere to call home, but we had these songs and we had these dreams,” that idea came to me a little bit later. At first, the original narration was a little more, “in 1991, I was a struggling musician. I threw everything in the van and we went down…” It was a little too, “Once upon a time…” So I came up with that other narration and then, after doing it, I realized, “Wow, this works great. It can apply to every single person in the film.” So Stevie can say the same thing, [Paul] McCartney can say the same thing, Neil [Young] can say the same thing. At some point in their life, you were so in love with music and so passionate about it that you threw everything else away and devoted yourself to that: “I don’t know what’s coming next, but I can’t wait to find out.”

Stevie: And you don’t care if you have to be a waitress.

Dave: If that’s the core of your foundation as a musician, then it never changes. There are some people that decide, “OK, I’m going to be a musician. I’m going to have a career. I’m going to go sell a million records. I’m going to retire and get a penthouse in New York City.” Then, there are other people that don’t know, but you’re willing to find out.

Some people might argue, “That’s easy for you two to say. You’ve sold millions of records around the world and played huge arenas.”Was there ever a time when you were struggling and you said…

Dave: “I’m going to quit music and get a real job?”

Yeah. “I love music, but I’m going to do it on the side. I have to make money somewhere else.”

Dave: Of course! You have to. I worked at a furniture warehouse and I fucking hated my job, but I played music on the weekends so that I could be a happy person. i didn’t play music on the weekends to lose my job at the warehouse; I couldn’t lose my job at the warehouse. I played music to make me happy.

Stevie: Or our parents looked at it as, “Well, it’s your terrific hobby.”

Dave: “At least you’re not out in a gang breaking into cars and stealing stereos.”

Though you two came of musical age at different times, the industry was healthier at either of those times, whether it was the mid-‘90s or the early ‘70s. Musicians today face a much tougher reality between a lack of monetary support from record labels, the new economics of music sales in the digital age and even higher gas prices.

Stevie: They’re hardly getting paid and [companies are] taking all their merchandising and part of their salary. They have nothing.

How do the new Stevie Nickses and Dave Grohls fight to be heard?

Stevie: It’s very hard.

Dave: The reason why Stevie Nicks is really popular is because she’s Stevie Nicks. There weren’t 10,000 Stevie Nickses trying to get a record deal back then or now. There’s just one. The reason why she’s so popular is because of what she does and not everyone can do what she does. It’s the same thing with, “Why did Nirvana become popular? Were there seven other Nirvanas in line waiting to put out a record at that time?” Not really. Kurt [Cobain] was an amazing songwriter with an incredible voice.

Stevie: And incredible charisma.

Dave: He was such a gifted person that if you had met another Kurt Cobain and given him a record deal, do you think the same thing would have happened? If you handed those songs to someone else and said, “Hey, record this record,” it wouldn’t have sounded like Nirvana because it wasn’t Nirvana. The reason why those things happened was because it was what it was, but at the same time, the industry didn’t really… they weren’t waiting for Nirvana to become the biggest band in the world. They pressed 3,500 copies of Nevermind the week it came out because they thought it would take six months to sell those fucking records. The reason why musicians become popular is because—I can’t say that because a lot of really shitty musicians become very popular— if you’re really great at what you do and you’re, in some way, able to share it with everyone, then you’ll be recognized for it. I believe that. You [also] have to define success. What do you consider success? I used to think, “All I want to do is fucking be able to buy corn dogs with money from playing music. Instead of selling equipment, I’d like to be able to play a show and feed myself. That would be awesome.”

Stevie: And have a cool little place.

Dave: I don’t think people should consider a career in music—I honestly don’t because, ultimately, you’re probably going to be disappointed—but it shouldn’t stop you from making music. Playing crazy, noisy punk rock in 1987 wasn’t going to kick Michael Bolton out of the charts, but everybody did it because they loved doing it. Look at the people in the Sound City movie: Neil Young. Why is Neil Young Neil Young? Because he’s fucking Neil Young, that’s why. Why is Paul Paul? Because he’s Paul. All of those people, I honestly believe, the reason why people appreciate what they do is they’re the only people that do what they do.

Stevie: Now, the record companies don’t have any money because a record used to sell for a certain amount of money or a CD sold for 18 bucks. The record company got $10 and then they put that in their coffers and they built that up so they had money to sign the new Dave Grohl or the new Stevie Nicks. [They] helped her or him to morph into the great person they were going to be or the great band they were going to be. Now, kids don’t have that because these record companies—fucking record companies—they can’t do anything for you. my record [2011’s In Your Dreams], that I love more than anything I’ve ever done, my record company didn’t help me with that. I went out and toured for two fucking years and said, “I’m on a mission. I’m going to play these damn songs, six of them, every night in every city I can until I can walk away and feel like I’ve done everything I can possibly do.” And I’m Stevie Nicks! So how is it for that little girl that’s 22 years old and is as good as me and writes great songs and is really cute and is ready to rock, but can’t support herself? There’s no record company that’s going to sign her or, if they do sign her, they’re going to change her into a slightly pseudo-rap artist and they’re going to make her wear creepy clothes and make her sing lyrics she hates and tell her she can’t do her own songs. Then her soul is going to die and then what is she going to do?

While Fleetwood Mac and the Foo Fighters are multi-platinum artists, touring is still—broadly speaking—how Grohl and Nicks make the bulk of their living. Selling out arenas around the world is common for both groups. If live performance pays the bills, then it also provides each artist with the place they yearn to be: the stage. Stevie Nicks’ ascensiontostardomhadas much to do with her gifted talent as a lyricist as it did with her live presence. The burnt-sugar voice combined with her iconic fashion sense—that exotic mixture of Victorian and bohemian—elevate her beyond a simple human when she takes on songs like “Rhiannon” or “Gold Dust Woman.” Dave Grohl is no fashionista but if you ask someone to picture him playing live—whether seated behind the drum kit or with a guitar strapped on—chances are they’ll picture him wearing a beatific smile. If you spend any time with him, you get the sense that the smile has less to do with his unexpected but deserved fame and more to do with a zen-like happiness of being able to play music for people willing to listen. And one suspects that the same smile, which addressed a crowd of 60,000 at last year’s Global Citizen Festival is one that was present in 1983 at a tiny club in Washington, D.C., when Grohl was drumming for the hardcore punk band Scream. The only difference now, it seems, is that thanks to technology, fans can say they saw the show without ever being there.

Is the experience of live music fading between the challenge of fans trying to score tickets to your shows these days and the Internet alternatives? YouTube exists now and every- one can see what the Sound City Players are about before they ever go to the show or try to get a ticket. Do you see people being weaned off of their interest in the live experience itself?

Stevie: Imagine how we feel up there knowing the first time that we played “You Can’t Fix This” or “The Man That Never Was,” [that] the second that we walked offstage, the whole world had already seen it on YouTube. That makes me sick. That makes me hate the Internet even more than I already hate the Internet. Does it make you hate the Internet, Dave?

Dave: Nothing will ever replace the live experience, being in a room where there’s a musician playing an instrument and they’re right in front of you— flesh and bone. That’s the ultimate experience.

Stevie: And what about the surprise? The mystery?

Dave: Those things—they’ve been challenged by the Internet, so you have kids that only sit and watch YouTube clips.

Stevie: And see it filmed from a really bad angle.

Dave: It will never replace the live experience—it just won’t— I don’t think.

Do you see value in something like YouTube?

Dave: Not as much as the live experience.

Stevie: Isn’t that really stealing? Isn’t that like coming in here and saying, “Boy, I love that coffee table. I’m just going to take it.” Why? Because we should share everything? Or that [cell phone ad] on TV that goes, “I deserve unlimited sharing to the whole world” or something. I’m like, “No, you don’t. You don’t deserve anything because you aren’t working for it. You’re buying a fucking phone for god’s sake.”

How different is it playing in a club or arena today than it was in 1993 or 1974? Does it feel different?

Dave: It doesn’t feel different to me.

Stevie: Not in a big, huge venue where you’re playing a big show— it really doesn’t feel different. It’s still that big, huge thing. It is weird to see gazillions of phones being held up. I preferred the lighters.

Dave: I remember the first time I ever saw an app on the iPhone with a cigarette lighter. I saw people holding those up. That one hurt a little bit. But here’s something funny, which maybe pertains to what we’re talking about. I came home a couple of months ago with The Beatles vinyl box set and both my daughters love The Beatles— they’re four and seven. I walk in the house and they see this big box set, and they’re like [gasps] “What’s that?” and I said, “These are The Beatles records.” They pull them out and they’re holding the records in their hands and they couldn’t wait to open them up, look inside, look at the sleeve and the liner notes, and see the picture. It’s not a little icon [as an album cover typically appears in a program like iTunes].

Stevie: It’s not even a CD.

Dave: I get the record player and I put it in [my daughter] Violet’s room and I show her, “OK, here is how you do it. You pull it out of the sleeve, you put the little stem in the hole there, you put the needle down—be careful. You’ll see this is the order of the songs, then you flip it over, there are more songs on the other side.” I left the room and I came back an hour later and she had all the record covers out on the floor and she was dancing by herself listening to “Get Back.” It was the exact same experience that you or I had when we were young, dancing in our bedroom, listening to all our records. The world’s changed, technology’s changed. The way we experience music, the way we listen to music, the way we buy music— it’s all different. But people are the same. She’s an almost seven-year-old kid having the exact same experience that someone had in 1959, 1965, ‘75 or ‘85. So human beings haven’t changed. When you ask the difference between watching something on YouTube or watching it live in your face, a human being, I’m pretty sure, will always prefer to see another human being doing it, live, in the flesh, because it’s tangible. It’s real.

One of the things that has changed over time are ticket prices. Fleetwood Mac may have had an expensive ticket in the ‘70s, but it’s not even close to where a Lady Gaga or Madonna ticket is today— they’re so much higher. How conscious are you of ticket prices?

Dave: Here’s how we look at it as the Foo Fighters. You know who I want in the front row? Kids that are dying to see a fucking show, kids that are going to go absolutely bananas when the band plays. Honestly, I don’t want a whole front row of people that just had a $900 dinner and are standing there, full of caviar and steak, watching the band. We try to keep it down. That’s just us, that’s our world. I’ve gone to see bands play before where I’ve shelled out a great deal of money to see my favorite band because of that experience I was talking about. That’s worth it to me. If a band that I really love comes into town and I have to buy a ticket, [then] I’ll pay $120 for it. I’ll pay $300 for it.

Stevie: I honestly don’t know how much Fleetwood Mac tickets are. Anybody know? [Stevie’s assistant relays the information that for most of the band’s shows, ticket prices are below $200 before service fees.]

Stevie: $200 is a lot of money.

Nicks is a luddite. She readily admits—nay, announces—that she doesn’t have a cell phone, never visits the Internet and certainly doesn’t spend any time on social media platforms. This stance is something of a double-edged sword for her: On the one hand it has provided blinders for her to focus more intensely on her craft than some of her peers, while on the other, it has left her ill-equipped to discuss the merits of technologies such as Spotify. Indeed, much to Grohl’s amusement, I found myself struggling to explain what Spotify was to her. For Nicks, the digital age and, most notably, the Internet, have created a domino effect of irreparable damage to the music industry: Music piracy means record labels have less money to support artists, which means fewer budding bands get heard because the labels can’t afford to financially nurture them. And, don’t forget, albums sales from Fleetwood Mac’s catalog could still make the band good money if consumers were still buying physical records and CDs versus streaming them or “illegally” downloading them. The new paradigm in which Fleetwood Mac makes fractions of a cent through royalties every time one of their songs streams on a service like Spotify or Rdio is a reality she doesn’t care to invest herself in. For Grohl, living in a digital world is simply a fact of life. He emails. He posts funny YouTube videos. He tweets. With regard to the aforementioned digital technologies, he’s aware of their various functionalities and shortcomings but he seems generally unfazed by their existence. In this way and others, Grohl and Nicks share something of a common attitude: I’m a musician and I make music for a living. How it’s being disseminated doesn’t really matter. What is important is how it’s created and that people are hearing it, consuming it and experiencing it.

One of the main issues addressed in the film Sound City is analog versus digital. To a degree, it rails against computer-based programs such as Pro Tools. Toward the end, you have Trent Reznor’s perspective of how you can use digital technology as a tool versus a crutch. Is it also fair to say that Pro Tools has democratized the recording process in that a kid in their bedroom now has the ability to suddenly create professional sounding music? Isn’t that a good thing?

Dave: That conversation is misunderstood a lot [as is] Pro Tools’ place in the movie. Pro Tools and the accessibility of digital recording equipment—technology—is, without a doubt, one of the reasons why a studio like Sound City couldn’t survive. anyone can make a record at home. Nobody really needs a big old studio and a big old Neve [console] like Sound City had. That doesn’t mean it’s bad. It’s inspiring that anyone can make a record at home. When I was 14 years old, if I had that laptop and that microphone and that program, I would have recorded a box set worth of music before I was 18. It would have been amazing. you know what I used to do, I had…

Stevie: Cassette to cassette to cassette to cassette—me too. 30 cassettes to cassette. It’s like ping pong.

Dave: A boombox and another boombox. you record your guitar on this cassette, practice it…

Stevie: Then you play along to that on this cassette, then flip that over, put the new cassette in. you keep going.

Dave: It sounds like a lot of trouble to go through.

Stevie: But it came out great because then it kind of mixed itself. you know what I do when I’m sequencing my records, I sequence from the CD onto a cassette.

Dave: That makes sense.

Stevie: I listen to it on my big-ass speakers and that’s how I sequence because that’s how it sounds amazing. Of course, it goes back to digital because I can’t do anything about it. But the sound of the cassette is so far superior to me.

Dave: I like the sound of cassettes, too.

Stevie: You go on the road [now] and [the record label] get[s] one extra room [where] they set all [the recording equipment] up. The fact is record companies can’t do much for you—your chance of getting a record deal is like a snowflake’s chance in hell. Getting anybody to help you or believe in you or not want to change you completely [is unlikely]. If you don’t have a hit single or if you do have a hit single and don’t have another one 15 minutes later, then you’re dumped, anyway— it’s like, well, maybe all this digital crap works. For us, the elite bands, we’re lucky because we can go on tour and make tons of money. But it’s [also] sad for us because we deeply would love for all these talented kids to be able to rise above and we would love to see a new Led Zeppelin come out of the wall. By the way, I’d really like to be in the buzzard group, too, just so you know.

Dave: The Vultures? [Them Crooked Vultures is a group consisting of Grohl on drums, Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones on bass, Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme on guitar and Alain Johannes, who’s played with the Queens, also on guitar. Founded in 2009, the group has released one record and looks to release a follow-up at some point in the future.]

Stevie: I just met John Paul Jones at the premiere of the [Led Zeppelin] movie [Celebration Day] and I’d never met him. I know Jimmy and Robert, but I’d never met John Paul Jones.

Dave: John’s cool.

Stevie: I fell in love with him.

Dave: He’s great; he’s a sweet dude.

Stevie: Oh my god, I want to be in that band.

Dave: OK.

Stevie: Watching him play in that movie, I had no idea. I never saw them live. [Fleetwood Mac] were always right ahead of them or right behind them. I never saw Led Zeppelin play. I was going to see them, I got sick, [and John Bonham] died. I didn’t get to see them. So I never realized how important [John paul] was until I saw that movie.

Dave: He was the sharpest tool in that shed.

Stevie: My god, he was. I kept telling [my assistant] Karen [Johnston], “Will you please remind me to tell Dave that I would really like to be the girl singer in that band?” Sorry, back to the other thing.

Dave: The wonderful thing about Pro Tools and digital recording technology is that it’s accessible and available to everyone—that’s awesome. The double-edged sword is that places like Sound City can’t necessarily survive. The whole sonic issue of digital versus analog, for me, goes out the window because I’m fucking deaf as a post. So if you were to A/B something that was analog and digital, I could probably tell you which was which, but ultimately, the thing that always bothered me the most about digital recording was the manipulation of performance. Once they realize, “Wow, the advantage of digital technology is you have all these ways that you can manipulate the performance. You can tune a vocal that’s out of tune, you can grid some drums that are out of time,” Things like that. That’s when people started [trying to] make it perfect. To me, that sucked a lot of the personality out of the music. When computers started showing up in studios, it took us a little while before we started using them, but everybody knew this was the future.

Stevie: It’s like Photoshop.

Dave: Right.

Stevie: Which is another thing I hate. It’s like photoshopping music.

Dave: And ultimately, it takes a lot of the personality out of the performance. It’s not the computer that makes these things happen. Computers don’t kill music; producers kill music.

Stevie: It’s the people.

Today, Fleetwood Mac is considered classic rock while the Foo Fighters are considered modern rock. What are your kids going to consider classic rock? What is Fleetwood Mac 40 years from now?

Stevie: Dead.

Dave: [Laughs.]

Stevie: But I’ll be watching. [Smiling.] always know, I’ll be right over your shoulder. you’ll feel the feather brush every once in a while. OK, Dave, you should answer that, then I’ll answer.

Dave: That’s the best answer ever. Hopefully, your kids will be listening to new music. I still listen to a lot of classic rock stations and songs that i grew up loving—the soundtrack of my life—but i still get excited when i discover a new band. like last week, I discovered a band i’d never heard before and they blew my fucking mind. They’re called Late of the Pier. They made one record and disappeared. They’re English. Nobody knows who they are. They use crazy computers and then they rock and it sounds like dubstep for one minute, then it’s a crazy prog thing, and it’s like, “Wow.” I don’t even know if they’re a band anymore, but it’s a great record. So hopefully, your kids will be listening to new music. When i think of Fleetwood Mac, and I said this today on the TV show [Late Night with David Letterman], music history is just as important as any sort of other history people learn. It’s just as important to know that Abraham Lincoln was the 16th president as it is that Lindsey [Buckingham] and Stevie met Mick Fleetwood at Sound City. Their music changed generations of people, and in that, changed the world. The Beatles changed the fucking world, Little Richard changed the fucking world. Nirvana changed a generation of kids.

Stevie: Buddy Holly.

Dave: Why isn’t that considered as important as the fucking last pope? To me, it’s just as important. So when i think about Fleetwood Mac, it’s more than just a band that made some records—they made history. It’s important for the next generation of kids to remember that. In an age where it might seem like music is split into so many different factions and it’s not important, it still is and it always will be.

Stevie: Back to radio for one second. I love radio. I loved radio as a little girl and I rocked in the car to it blasting. I hope that radio will always be. When Tom Petty wrote that record The Last DJ, he was so pissed off. I think the last DJ was Jim ladd—that’s who he wrote it about, I’m pretty sure. Because we loved radio so much, it’s such a part of our life. We want great radio to be forever and it’s not now. I wish I had that real magic wand and could wave some fairy dust around and get radio back, like it used to be. Because it was so much fun, driving around, listening to the radio. That’s probably why I don’t drive anymore—I haven’t driven since 1978—but that was something i loved. [There’s] nothing better than driving down the highway with the radio on. i hope that the gods [and] the spirits will fix it all. That’s what I hope—that they’ll look down on us and figure out a way to fix it so that the new little Foo Fighters and Fleetwood macs and led Zeppelins will be able to rise up so that in 20 years, they can listen to something else besides just us. Because otherwise, in 20 years, they’ll just be listening to us. Good for us, but not so good for anybody else. They’ll still be listening to led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Foo Fighters, Fleetwood Mac, Nirvana, The Who and all those great bands. But there won’t be anything new because nothing lasts. I want stuff to start lasting again.