B.B. King: Lessons from the Original Guitar Hero

This artice on the late, B.B. King appeared in the December 2008 issue of Relix.

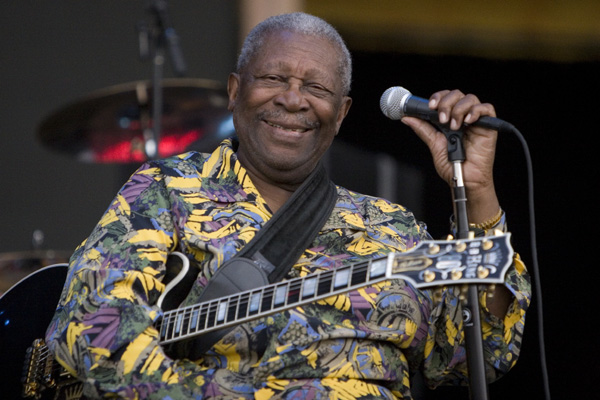

Having recently turned 83, and with 2009 marking 60years since the birth of his recording career, B.B. King has a healthy sense of humor about his age. It wouldn’t be offensive to describe him as over the hill. At least, he wouldn’t take offense to it: On the phone from a hotel room in Toledo, Ohio, he’s just described himself as such, before referencing the 1969 movie The Over the Hill Gang, gleefully likening himself to the cast of grizzled Texas Rangers called back into action in the film.

So when the notion is put forth that a considerable slice of his audiences these days may be snatching up tickets quickly because they might just be eager to see him once—or one last time—before he expires, it’s not met with a knee-jerk “Excuse me?” or an uncomfortable pause, but rather roaring laughter, a moment spent further considering the notion, and then more belly laughter.

“Maybe that is it,” he says, laughing some more. “That’s funny!”

To that end, King said he had a little fun ribbing T Bone Burnett, the producer of his lauded new disc, One Kind Favor, which takes its title from a line in the album-opening cover of the Blind Lemon Jefferson/Furry Lewis tune “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.”

“While we were recording it, I was telling T Bone, ‘It’s coming up to my 83rd birthday. Are you trying to tell me something?’” he says with another big laugh. “I thought it was pretty good of him, but I didn’t know they were gonna name the CD after it. My kids don’t like it, but it’s alright with me… What’s the old saying? ‘Once a man, twice a child.’ I’ve been a child once, and now I’m starting to be another one.”

***

It’s an apropos metaphor for his career right now, as much of what is happening in King’s professional life is bringing the original guitar hero full circle. On his birthday in September, he saw the opening of his own museum, which is also an educational center of sorts paying homage to all the great bluesmen who came before him. One Kind Favor, meanwhile, finds King tipping his hat to some of those very men (Lonnie Johnson, John Lee Hooker and more obscure talents like Lee Vida Walker and John Willie “Shifty” Henry). Some of the songs on the album, like Johnson’s “Tomorrow Night” and T-Bone Walker’s “I Get Weary,” are among those that he himself spun as a disc jockey in Memphis in the late 1940s. Coincidentally, some six decades later, King recently returned to that role with B.B. King’s Bluesville, his new program on XM Satellite Radio.

What’s more, if he began his career as a radio stump man, singing jingles for the long-gone tonic Pepticon—a surviving bottle of which, rather miraculously, appears in the new museum—that part of his life has come around again, too, in a way. Not a concert or interview passes without him campaigning for better awareness of those bluesmen who predated him. For King, both the stage and the interview are platforms to hail the men to whom he owes a debt—from Robert Johnson to Jimmie Rogers—and the generations of gifted players who idolize him, friends like Eric Clapton and Robert Cray and younger talents like Kenny Wayne Shepherd and Jonny Lang.

Preaching about the blues, supporting its young faces and carrying the torch for the music is an ongoing concern for its most famous practitioner, as it is for Buddy Guy, more than ten years King’s junior. In front of audiences or tape recorders, both speak to the importance of keeping the music alive. And for good reason: Over the last few decades, they’ve seen the music tumble far below the radar, marginalized and ghettoized within the music industry. King’s one beef with the music biz, he often notes, is that it’s damn near impossible to hear blues music on the radio.

The music may have been the very seed of rock roll, but today its forefathers are fading into obscurity, which is a reality that can smack King himself in the face rather abruptly from time to time, he says: “I remember going to Australia once, and I found a young man that played as close to me as I guess anybody I’ve heard, and he didn’t know who I was. He tried to play like that because of his dad. His dad knew me and his dad tried to practice me, but the boy got it and didn’t know anything about me. But that’s the way it is with a lot of the young players, because they’ve heard other people—not from the source.”

All that considered, he relays with pride that long after he’s gone the torch-bearing he’s doing now will continue at his museum in Indianola, Mississippi. Beyond the cases of Grammys or videotaped testimonials, it’s the homage he enjoys most: “Robert Johnson. Jimmie Rogers. Big Boy Crudup. John Lee Hooker. Muddy Waters. Jimmy Reed. I could just name you so many that are deserving as well, if not more. So they have promised that this will be a musical and interpretive center, educationally, and that makes me happy. If it takes my name to get these guys to be recognized as I think they should have been a long time ago, then that makes me happy.”

But it’s not just the spreading of awareness for fallen singers and guitar players that he finds enticing about this wing of the museum, it’s the notion that genuine education will be taking place in his name. A full-fledged farmhand who chopped and picked cotton from age seven, he saw his mother die at nine and was plowing fields and driving a tractor while barely a teenager. That he was never able to finish high school is still one of King’s greatest regrets in not furthering his education. And it shows.

Considering his iconoclastic and revered status , it’s more than a little disarming during a 90-minute conversation to hear his insecurities over his vocabulary and uncertainty over whether the story he’s using to drive home a point is “making any sense or not.” It’s why part of his daily ritual is to learn a new word, or to learn something from the many people he meets on the road. During our chat, for example, I ask for his take on the now-disappearing wave of North Mississippi Hill Country bluesmen, Fat Possum all-stars like Junior Kimbrough, R.L. Burnside and T-Model Ford. Although unaware of each, he asks me to send him some of their CDs, so he can get better acquainted with their music.

“When I’m listening to people talk who’ve been to college and finished high school, I feel second best still to this day,” he says. “I feel a little jealous. It makes me want to go home and pick up a dictionary or an encyclopedia again and try to remember words that I heard and find out the meaning of them.

“See, it seems to me that education is the answer to the world’s problems,” he continues. “I firmly believe that. I’m a diabetic. I’ve been one for a very long time, and I firmly believe that some day, some person that’s in school now will find the cure for diabetes, and a lot of the other problems, the diseases and such. And it will take education for that. And I think the turmoils and the things that we’re going through at the moment—the banks and the money and all that stuff—we’re gonna need some education for that, people that will straighten it out, togetherness as well.”

Due to his diabetes, which he’s lived with for some 30 years now, and other ailments, King’s finally beginning to see his days on the road dwindle, however so slightly. If there was a time when he was averaging 250 dates per year, he’s now playing about 100. “It’s been four or five years since we’ve had an empty house, it’s usually at least 80-90 percent sold out, generally, every night.”

Proudly, King, who now lives in Las Vegas, notes that he and his bands have brought the blues to more than 90 countries in the world over the past 60 years. And he’s equally quick to note that he’s endured 18 car accidents along the way. They’re almost like the war medals he never earned in the Army. Curiously, he even randomly mentions that brief stint in the military (At 18, he enlisted in 1943, at the tail end of World War II, but because of his tractor-driving skills was deemed too valuable as a civilian worker, and was rejected: “I had a short term in the Army. I didn’t finish basic training,” he says. “If I die tomorrow, I wouldn’t get a flag.”).

Of course, all that traveling began with the short, pivotal trips he would make from the Indianola area to Memphis in the late 1940s. In his early 20s by this point, King had already logged a decade as a farm hand—“Remember, we didn’t have child labor laws then”—and was eager to better his life. When he first got to Memphis he experienced quite a shock in finding a relative ton of black singers just as talented as him singing in what was then Beale Street Park. Destiny would eventually guide him to radio station WDIA, where the man born Riley B. King would be transformed into the Blues Street Blues Boy, later shortened to “B.B.” King. It was there that he would cut his first slabs of vinyl.

“I knew if I got on the radio, I would be able to make about 12 dollars and a half a night,” he says, adding with a big laugh, “So, boy, I’d almost kill for a radio job. I was lucky. They had just started an all-black-operated station in Memphis [the first in the country], and I managed to get on it, first as a guy advertising one of the products.”

Eventually, he began playing records—whatever he felt like playing: “I played things that I thought should be played, and I believed that every style of music should be played,” noting that that will again be the format for B.B. King’s Bluesville. “That don’t mean you have to continue to play ‘em. But if you play it first, it’s like sending a bill to congress: If they never get the bill, they don’t know how to vote on it. So you need to be able to play something on the radio so people can hear it and they know what they like and what they don’t. If they don’t like it, you’re not gonna hear much about it. My motto was—and still is—that people deserve the right to hear it, and they make their own decisions.”

To a large degree, when it comes to Bluesville, King says he’ll be following the lead of program director Bill Wax, a radio man with some three decades of experience. “In a lot of cases, Bill knows the tunes better than I do. I’ll be doing monologues, and telling stories of people that I know who kind of guided the music to where it’s at today, and I think that I can do that pretty well.”

***

While he’s never downloaded a single track in his life, B.B. does use a laptop and Mp3 player, presumably preloaded by an assistant. “I don’t do email, but I text,” he says. Before he picked up the phone for this interview, he was going over some new musical ideas, “plotting out a few things,” he says. “Every day is important, man. We never know how long we live, or will live. I’ve been doing pretty good for all these years, and I still get around and have a ball playing. Every day is a new day, and it’s a good day to try to get something done.”

Considering his zest for moving forward in life, it was interesting that producer T Bone Burnett insisted that the way forward for King, legacy-wise, was to take a few steps backward and recapture some of the grit and sonics of his vintage 1950s recordings. King was all for it, he says: “What he wanted was something I wanted for a long time—I thought that was a little bit more me than some of things I’ve done later in my career. He sent me a list of songs, and I sent him a list, and we came pretty close to picking the same things.”

Hailed for his work with everyone from Gillian Welch and Bob Dylan to Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, Burnett nudged King to let go of some of the safer recording routines he had fallen into in recent years, eventually feeding his guitar through a couple vintage tube amplifiers. The disc, which also features the talents of Dr. John and celebrated session drummer Jim Keltner, focuses less on B.B. King the celebrity, the entertainer and the brand, and more the voice, making One Kind Favor a rare, deep Delta blues album for the genre’s flagship player, full of feeling and grace.

At the risk of cliché, it’s worth noting that if he never cut another side, the smoldering, disc-ender, King’s rendition of Lonnie Johnson’s “Tomorrow Night,” would work as good as any final word on his career, as a goodbye.

King’s not sure about all that, still to this day shy about the compliments heaped upon on his career. “Some people say I revolutionized the sound of the guitar. Well, some of the things I point to, yes, I agree I hadn’t heard it before I played it. But, to be honest, it just makes me feel good that I was able to do something that somebody liked.”