Band of Brothers: Pearl Jam Marches On

With the news that Pearl Jam will enter the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, here’s a look back at our 2006 cover story on the band as they readied their self-titled record.

With the news that Pearl Jam will enter the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, here’s a look back at our 2006 cover story on the band as they readied their self-titled record.

“The Star-Spangled Banner”

The house lights in Washington D.C.‘s MCI Center have been on for almost 15 minutes when Pearl Jam bassist Jeff Ament takes a seat at the foot of drummer Matt Cameron’s kit and cracks open three beers for himself, Cameron and guitarist Stone Gossard.

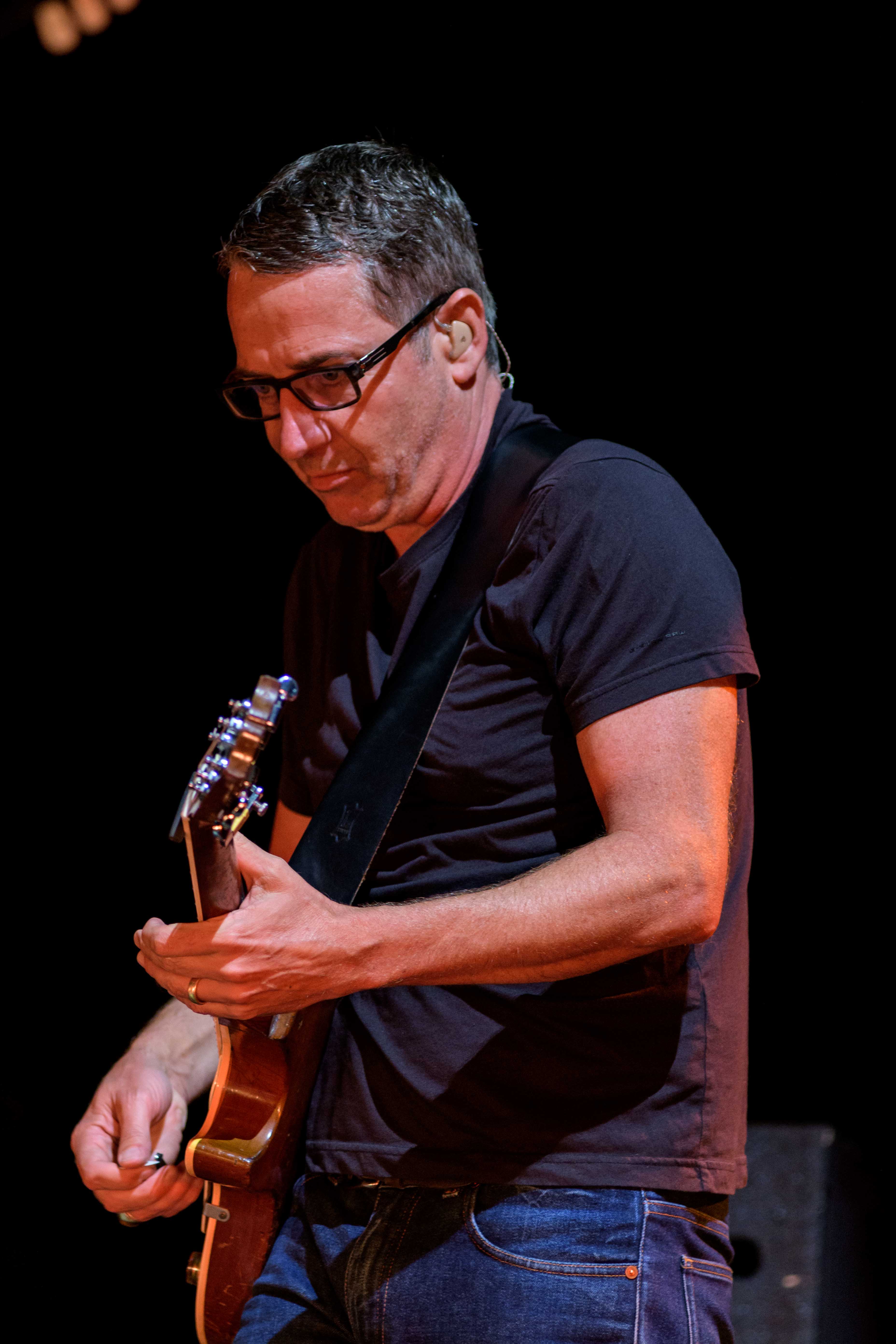

With beers in hand, sweat dripping, they stare at guitarist Mike McCready, who is finishing his solo on the band’s seminal show-closer, “Yellow Ledbetter.”

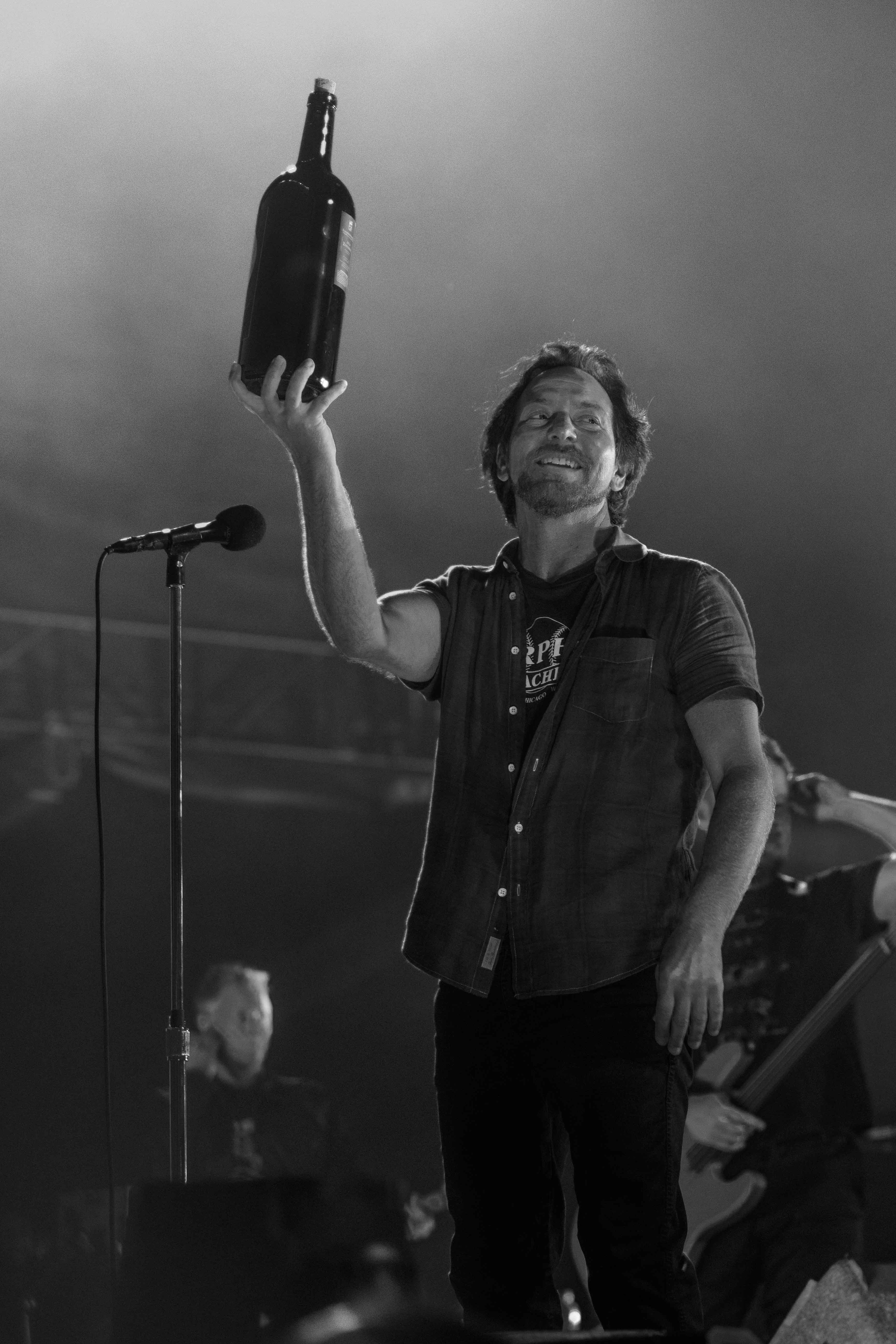

Meanwhile, Eddie Vedder is offstage, taking a drag off a smoke, swigging from his bottle of wine, looking out at the crowd. McCready holds the last note for a second or three. Then, with his eyes closed, his right hand strikes the opening riff of “The Star Spangled Banner.”

The audience of 20,000 is shocked into a “Holy shit, this is going to be a special moment” awareness. People stop dead in their tracks on the exit stairs. Even the doughy, cantankerous front row security guards are drawn in.

McCready, one of the most underrated yet copied guitarists of the modern-rock era, is taking on one of the most listened-to songs in the world. It’s a move that could be audacious – or misconstrued. Capping a show during a week in which the war in Iraq raged on, McCready’s improvisational “Star-Spangled Banner” reclaimed the majesty of the anthem for the people. Fans in the crowd openly wept.

Vedder and his friend, political punk-rock governor Ian MacKaye (Minor Threat, Fugazi, The Evens) peer out from side stage at the crowd, which is now fully involved as one. Ament, Cameron and Gossard put down their beers to applaud McCready home to the anthemic, uproarious ending. The entire band then joins a happily dazed McCready at center stage for one last, triumphant bow.

“It’s a piece of music I felt that I wanted to do. It’s not something that belongs to Republicans or Democrats. Or anything,” says McCready in New Jersey on June 3rd, when we sat down to talk. “I’m doing it because I can. And I want to do it.”

McCready’s love of fellow Seattleite Jimi Hendrix’s version at Woodstock was just as engrained in him as saluting the flag in school. He would practice for hours in the mirror, trying to copy his idol’s style.

“That’s the version that really means something and touches my soul,” McCready admits. “As a little kid, I was conditioned to salute the flag from kindergarten on. When I do it [now], I go someplace different and I’m kinda shaking afterwards. Something happened that night [in D.C.], and I don’t know what it was. The more I do it, the more it’s happening. The less I think about it, the more I can freely let it come.”

“Inside Job”

It’s said that religion is for people who are afraid to go to hell and spirituality is for people who have gone there and lived to tell. If that’s the case, then Mike McCready is a humble spirit living in the material world.

He’s endured a serious entanglement with Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease that causes swelling in the intestines. It is one of the most painful ailments the body can endure and it can strike without warning. He’s stopped smoking in the past year and now is in full freak-out mode aerobically on stage. But it took work, inside and out.

“When I start complaining about my situation, I have to know that people are in far more painful situations than I am. They are stronger than I am in many situations, like a fifteen-year-old kid in a wheelchair.”

The emotional track “Inside Job,” from Pearl Jam, is the first song to which McCready has penned lyrics.

“‘Inside Job’ was searching for some type of spiritual solution. To be able to write that song and then have everyone in the band want to do it was fucking awesome,” he relates.

But first he had to give it to Vedder. Despite their longtime friendship, McCready was nervous that Ed wouldn’t approve. “I was nervous because I had written the lyrics out, knowing that he had a lot of shit on his plate,” he laughs. “It was like I gave him a full dinner, another extra course.”

McCready then did something he rarely does. He sang to Vedder. “It was pretty nerve wracking,” he confesses. “But he was into it. It was cathartic to actually put some lyrics down and not feel self-conscious or embarrassed by it.”

Today, he knows that whether he’ll have a good or bad day is dependent on him and part of ensuring a good day is by helping someone. “It’s important that these issues are talked about. These are very embarrassing issues for someone who is 15 years or 40, when you shit yourself. And it really fucking hurts right before it! And it gets worse than that,” he says candidly.

“If my coming out and talking about it helps anybody, then it’s all in a day, even more so than the band. It’s more important.” “I think we have an example of a musician who exorcises some demons on a nightly basis,” says Vedder. “In a way, it allows anyone who attends the performance to do the same. He’s channeling things that are positive and he’s channeling things that are negative. It’s fairly deep what he’s doing, considering his back story and what he has overcome.”

Jeff Ament, who has shared a side of the stage with McCready since the beginning, marvels at McCready’s complete transformation. “A lot of it was us not giving up on him. We knew what a special talent he was and what a great person he was. It’s amazing how much further he has taken it, beyond getting sober, beyond dealing with Crohn’s. He’s totally gone beyond all that stuff,” says Ament. “He’s a big part of why it’s a totally different band: It’s because he is 100% there and has been for the last couple of records for the first time. There is a complete connection in the band now. All the time.”

“Hard to Imagine”

Bassist Jeff Ament went through music-industry hell before the success of Pearl Jam. Along with Gossard, he was a member of Mother Love Bone, a band that was destined for huge things. Just as their star began to rise, the overdose death of lead singer and friend Andrew Wood derailed Ament and Gossard.

“When we had started this band [Pearl Jam], I don’t think any of us had been in a band for more than two or three years. Or any kind of relationship for more than two or three years,” admits Ament. “Your expectations for longevity are pretty small: Maybe we’d make three records… You think you’d do it all in that three-record span. “At different times, the band has been important to different people. I think that has helped keep the band afloat. There were times when somebody wanted to give up,” he reveals. “Then the other person is there reaching down, saying, ‘Come on man, good things are gonna happen, better things.’ And it’s true.”

With all of the band members having crossed the 40-years of age mark, in some instances starting families of their own, a certain maturity was bound to happen.

“We’re coming to a new level of understanding and history with each other. There is respect,” says Gossard.

Yet he knows that without Vedder, there is no Pearl Jam.

“More than anything, Ed really likes the band,” says Gossard. “He likes being in this band. He respects it and is excited about it. You can feel that. He could have done anything he wanted to.”

Indeed, Vedder could have split and cashed in on a solo career. Instead, he collaborated with the likes of Pete Townshend and the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. He went surfing. He went to ballgames. He chose to remain.

“It’s a metamorphosis,” explains Ament. “There is a stronger brotherhood now than there’s ever been. I certainly feel closer to everybody than I have ever felt; it’s mainly because of communication. If you have an issue you just knock on the door of your brother and say, ‘Hey man this is going on, it’s no big deal, but I just wanna let you know.’

McCready, the band’s resident optimist, is stoked by its recent resurgence. “It’s super positive. Everybody is saying it’s a re-birth and the energy certainly feels that way to me. It’s pretty funny. Before, I had to tell people we had a record out. Now my friends are calling to tell me they’re sick of hearing our song on the radio,” he laughs.

“It’s interesting that, A: We’re still around and we’re playing music. We get along and talk to each other as a band. B: We have these fans. I ran into a guy who said he had been to 52 shows; I was like, ‘Fuck!’ That’s astounding to me.”

“State of Love and Trust”

Forty-three-year-old Brian Leslie is more than a fan: He’s a conduit for change. Buoyed by McCready’s dedication to fighting Crohn’s and colitis, Leslie hatched a plan to spread the word and help fight the disease.

As a longtime member of PJ’s fan club, the Ten Club, Leslie has been privy to many up-close seats and has caught his share of guitar picks. Then he got an idea: Scan an image of a pick and make a T-shirt. Give them away and trust the person to send in money to the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA).

“I don’t want anything out of this,” says Leslie, rifling through a box of shirts outside of The Boston Garden. “If the fans can step up and help out, then that’s even better.” Word of Leslie’s actions spread before show time; people stopped each other on the street, asking where they could find the shirts.

By show time, even the band had noticed. Jeff Ament asked for one from the stage and came out wearing it for the encore. Vedder caught one and also donned it for the encore. By the time the tour swung through D.C., the shirts were almost hotter than the tickets. Crew members clamored for them, fans posted on message boards and, above all, money was raised.

“We’ve started getting checks from all over the Northeast,” says Steve Wright, President of CCFA’s Northwest chapter, from his Portland, OR office. “It’s amazing that the word is getting out, and people are doing this on their own.”

When McCready discovered that this grassroots act of compassion was being bankrolled by a fan who didn’t ask for anything in return, he was overwhelmed.

“Really? Wow. That’s the kind of shit that I…” he pauses, stops strumming his guitar, then lets out a breath. “It touches me deeply because I forget that people will have that kind of a heart and be positive and that they’ll take it upon themselves to do that. That’s the coolest way for things to happen: organically. That’s pretty fucking rad.”

Pearl Jam’s fans are a proactive bunch, and many (though by no means all) follow the politics of the band, supporting its causes, such as “Free the West Memphis Three,” The Innocence Project, the Surfrider Foundation and many others.

In fact, what Vedder calls “one of the greatest musical highlights of my career” happened the first night the band performed in Camden, when three wrongly-accused men freed from prison by the Innocence Project – Wilton Dedge, Tommy Doswell and Vincent Moto – took the stage with Pearl Jam to perform “Last Kiss.”

“It was so powerful,” says Vedder. “There were three men on that stage who had over 50 years of false incarceration between them. It was one the most memorable moments of our lives playing.

“We’re humbled by the fact that things take place outside of the actual concert. Fans are becoming friends. They’re getting married, having kids, participating in their communities… Beyond any song I can be proud of writing, that’s the stuff we can be most proud of. We didn’t even try to do that, it just happened. “I feel not only do I relate to the people in the audience, 90% of them, if not more, are cooler than us,” laughs Vedder. “I see healthy couples, healthy individuals, healthy families, healthy adolescents and it seems like they are onto something in their own lives and we are a small part of it.”

Gossard will be the first to tell why the respect has nurtured and grown: it’s Vedder’s ability to communicate from the stage “First and foremost, it’s how Ed interrelates with the audience in the arena when we are playing. He respects the audience in a way that is not always there with rock bands. He’s able to trust a bigger process than is typical at rock shows.”

Gossard will be the first to tell why the respect has nurtured and grown: it’s Vedder’s ability to communicate from the stage “First and foremost, it’s how Ed interrelates with the audience in the arena when we are playing. He respects the audience in a way that is not always there with rock bands. He’s able to trust a bigger process than is typical at rock shows.”

The Ten Club is more than a fan club: it’s a way to interact with the band by buying tickets, recordings of live shows, merchandise and supporting its causes.

“It’s an ongoing manifestation of how we have sorta tried to do things since the beginning,” says Gossard. “If we can do it ourselves or there is a way to creatively try something new or to think about it, bend the rules or even break them, we’re interested in it. “But if you had asked me in 1991 if we still would have been a band in 2006, I probably would have thought that we wouldn’t have been,” admits the guitarist. “But I like to dream, too.”

Alive or Dead?

Ten years ago this fall I had an epiphany at a Pearl Jam show. It was September 26, 1996 on Randall’s Island, in New York City.

The rain was teeming, coming down sideways, the wind was howling off the East River in a circular motion and the temperature was dropping by the minute. This was before the band even reached the stage.

In a moment of clarity I thought, “The only other fans that would deal with these elements are the Deadheads.” I knew this first hand, having seen the Dead over 70 times. Now, ten years down the line, and the comparison has even reached the mainstream media. I could barely believe my eyes when I saw four words that I’ll never see again in GQ Magazine: Grateful Dead, Pearl Jam.

Vedder loves to joke about his band’s recent comparisons to the Grateful Dead.

“As opposed to Dead shows, they’ll actually remember the concert the next day,” he laughs. “That of course is [said] with grateful affection towards The Dead. People kept coming back because they wanted to remember the gig, if they hadn’t from the night before,” he laughs.

But it’s the anything-can-happen-at-anytime atmosphere that’s the correlation for many. In Boston, the band said “screw you” to the curfew, playing a full half hour longer and incurring the financial wrath that comes with breaking the rules.

“Heads” and “Jammers” are different, though. Not too many “Jammers” follow the band, except in the dense Northeast. No one is selling grilled cheese sandwiches in PJ parking lots or pushing nefarious wares to get by.

The true parallel between the two bands is the personal connection to the music. To this writer, the music of both Pearl Jam and The Dead have ridden shotgun through every breakdown, breakthrough or breakup that I’ve gone through in my adult life.

“I think that feeling of people feeling that they have a history with us and that openness of wherever the night takes us and we reach this level of joy together…The crowd feels it. It’s very simple – it’s not about complexity or anything sorta rigorous,” explains Gossard.

Lead singer Jim James of My Morning Jacket knows this feeling as well. He witnessed it every night on the first leg of the American tour, when MMJ served as the opening act, but for him it started much earlier, as a seventh grader in Kentucky.

“The first group of guys I met in the seventh grade, the one thing that brought us together was music. That was when R.E.M.’s Out of Time was big. Then Pearl Jam, Nirvana, Alice in Chains and Soundgarden hit. We used to cover “State Of Love and Trust” and “Alive,” all these Pearl Jam songs, in the garage,” he reveals on a sheltered patio backstage in sweltering Camden. “Being in seventh grade and being totally in love with these guys and then sharing a stage with them is surreal. “It blows my mind to see that many people every night latch onto every syllable, every note that Eddie sings. It’s a force. You hope that your music can connect that way where you can be a force like that. It’s like 20,000 people doing a concert together.”

During the first night in Camden, during the extended jam that has made “Porch” a live spectacle of sound and light, Vedder uses his guitar as a spotlight, beaming the metal of guitar off the stage lights. Like a wave, the light rolls across the huge shed.

“There are people in the furthest rows who are feeling it as much as those in the front. I kinda can’t explain it,” Vedder reveals. “But, I can’t imagine it without that. I can’t imagine playing to a seated crowd. Not at a Pearl Jam show, anyways.” “It’s the very simplest of joys,” explains Gossard. “To run around and strum chords with your buddies until something vibrates loose and breaks free and then you all can stare at it and enjoy it, with everyone participating in that, is this enormous, powerful feeling.”

Like the Dead before them, Pearl Jam has its (albeit smaller) share of show-tripping fans. In order to get a feel for road trippin’ with Pearl Jam, I bummed some rides from show to show, city to city. On my first night in Boston, I met a gaggle of Canadians who had driven Pearl Jam’s entire Canadian run in the fall of 2005 in a 1989 Dodge Ram van. They documented their trip and put out a DVD, entitled Touring Van, with the blessing of the band. Our travel plans meshed and I was now onboard.

Driving in a van with six people without air-conditioning during the Northeast’s first heat wave of the year was an experience. The traffic sucked and the van stunk of stale beer and the sweat of dudes who wear wool socks in June. I loved every single whiff of it.

The van’s owner, 27-year-old Jason Leung of British Columbia, left his job as a civil engineer to tour. “Newfie Joe,” of Newfoundland, who bills himself “the smallest oil roughneck you’ll ever meet,” was the van’s resident hell raiser. The weak American beer ran through the heavily-bearded, five-foot-five 120-pounder. His karma was supreme, talking the notoriously badass Camden cops into posing for a picture and narrowly escaping a beatdown in South Philly when he strolled up to Pat’s Steaks, video camera in hand, and said about Pat’s arch rival and neighbor Geno’s Steaks, “Geno tells me his steaks are better.”

Each of the Canadian riders had quit his job as restaurant manager, engineer or computer tech to follow the band. Fans took them in, fed them, housed them, got them tickets, following their trek on their website, touringvan.com, and the PJ message boards.

“I should be interviewing you!” laughs Vedder when he catches wind of my adventure. “How was it?” “Stinky. And they would have ended up in Cuba if I didn’t navigate, but I have never met kinder, more genuinely nice people in my life,” I told him. “That makes me so happy,” says Vedder, “so very happy.”

“Green Disease”

“This one is for the connoisseur,” announces Vedder on the band’s second night at East Rutherford as Pearl Jam launches headlong into the rarely-played “Alone.” A third of the way into the B-side nugget, the stage power went dead. No sound, or as they say in Jersey, “no nuthin.’” After a technical adjustment, they picked up exactly where they’d left off, right to the exact measure. “I thought Bruce would have paid the electric bill before he went on tour,” jokes Vedder after the brown-out.Jokes aside, the band takes its energy consumption quite seriously, proactively taking measures to reduce its negative contributions to the environment. “We use a lot of energy going out on the road: we’re taking flights, we’re in a lot of buses, in a lot of trucks, a lot of electricity, a lot of hotels, drink a lot of water and that stuff adds up,” admits Stone Gossard, when I caught up with him in New York City.

One’s first impression of Gossard is that he looks smart. Thin, sporting small designer glasses, short hair and scrubble on the chin, it would be impossible to tell him apart in a room full of code writers and biochemists.

The 41-year-old’s activism was instilled in him by attorney parents, as well as at Seattle’s Northwest School of the Arts. A keen environmentalist who enjoys scuba diving, Gossard and Pearl Jam support environmental groups ranging from surfer Vedder’s pet cause, the Surfrider Foundation, to Honor The Earth, Conservation International and the Washington Wilderness Coalition.

“One of the things we’ve done on this tour is use 100 percent biodiesel on all the busses. Biodiesel has much lower carbon emissions and it’s grown in the United States. I don’t think biodiesel is the end-all solution, but it’s a great alternative energy to get people thinking of the options. “More important is how far stuff has to travel to manufacture it. Stuff is flying all over the globe. My intuition tells me the more stuff you can do closer to home and using people who work locally, the better off you are,” he adds. “You hope by doing local things you are basically saying, ‘I have more connection to it’ and are more aware of that thing I’m doing than I would be if it was being done in Singapore or someplace where you might not really know what is being done on your behalf. “When you’re doing it on a large scale, that can be contradictory, so you have to try and find a balance. We’re signed to an enormous label that has offices all over so we certainly have a lot of connections to big multinational corporations,” Gossard acknowledges.

To offset its environmental impact, Pearl Jam presently uses an eco-pak for its CD packaging, which employs a higher ratio of cardboard to plastic, and is taking steps to integrate U.S.-grown organic cotton into the band’s T-shirts.

“It’s a fine line in terms of talking about it, being critical of it and participating in it,” says Gossard.

“Marker in the Sand”

Vedder is not an armchair quarterback, nor a guy who thinks he knows it all. He’s largely self-taught. And, like the band’s eco-consciousness, Vedder walks a determined line catalyzed as much by consternation as conviction. He speaks with returning war veterans, marches in antiwar rallies, watches CNN daily, reads newspapers, and checks the government’s checks and balances. At 41, he’s now a doting dad to a two-year-old daughter, Olivia, and he doesn’t like the idea of his child growing up in wartime.

“This morning on CNN, I saw Michael Berg, the father of Nicholas Berg, the kid who was beheaded by Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi. They asked him, ‘How much longer should we wait to pull out?’ Mr. Berg said, ‘I wouldn’t wait 12 minutes, because in 12 minutes, someone else will die.’ That’s the bottom line: the loss of lives. And there’s no vision for an ending yet.”

Most of Pearl Jam’s self-titled new record, which was released on J Records in May 2006, has to do with the current state of the union. Songs like “Unemployable,” “Army Reserve,” “Come Back,” “Marker in the Sand” and “World Wide Suicide” are as much political statements as they are great rock songs.

“World Wide Suicide” is the biggest single Pearl Jam has had in years; as of print, it was at No. 17 on Billboard’s Hot Mainstream Rock Tracks chart. The song at one point hit No. 2 on the chart, and has been on it for 14 weeks. The song is about U.S. soldiers in the Middle East and one soldier in particular: Pat Tillman, a former pro football player-turned-soldier who was killed by friendly fire in Afghanistan in 2004.

The Pentagon has been accused of allegedly suppressing the damaging information surrounding his death, keeping it from his family and withholding the knowledge that he was killed by friendly fire, so they could use the All-American Tillman as a martyr for the war.

“It’s [“Marker in the Sand”] about him and a bunch of the guys who didn’t get as much coverage – the guys who barely got a paragraph instead of ten pages,” Vedder says. “The thing about Tillman was, he got ten pages but they were all lies. His family is being blocked by our government in finding out what really happened. “Where are the leaders that are going to represent a galvanized view on what to do next?” he asks. “Democracy might have a chance at working if people educate themselves on these issues and make their opinions known.”

During the band’s set in D.C, Eddie Vedder was not in a jovial mood. With his piercing blue eyes, he looked, well, pissed off. He certainly wasn’t the “I’ll rip off your head and shit down your throat, eyes rolling to the back of skull, frothing at the mouth” Eddie of 1993. But there are moments when his now-more-refined rage comes to the surface, and these moments usually make for great art.

“I know I’ve been agitated a couple times on tour, but I don’t remember why, when or where,” Vedder laughs. At the second night, in Camden, he threw a towel at a photographer who overstayed his welcome, but in D.C., it was obvious at whom and what he was angry. “I pledge my grievance to the flag,” he sang on “Grievance” with vitriol. “‘Cause you don’t give blood and take it back again, we all are deserving of much more.” It pains him that, as he sees it, the country was hoodwinked into the war in Iraq. It hurts him that soldiers are coming home in caskets. It burns him that liberties are being sacrificed in the name of homeland security. “You’ve got an administration that does all this work that is covert and undercover. They willed the country to go to war. They lied to us on deep, criminal levels about WMD’s,” he says. “The worst lies they told us was that diplomacy had been exhausted, while all the while they were planning to go in, whether it was unilaterally, preemptively or fundamentally. They did all three. “Now you’ve got people confused over whether we should stay now that we are there. Other people say we have created and are supporting one side of a civil war. It’s a mess. “I don’t think any Democrat or Republican is going to lead an antiwar movement until there is a shift in the polls that says that movement will be supported. If people are united, forceful and opinionated in letting their voice be heard and they support an antiwar candidate, then we will get one.”

Contrary to the often taciturn image of Vedder portrayed by the press, he’s not above telling a Dick joke from the stage when he’s at our nation’s capital. “I got a disturbing phone call in my hotel room today. I picked it up and said, ‘hello.’ The voice said, ‘Hello Eddie, this is Dick. Dick Cheney.’

‘Hello… Dick,‘” Vedder deadpans. “I asked him how he got my number. He said, ‘I have a few friends over at the NSA. I was wondering if you can play a song that I listen to every morning.’” Vedder then lead the band into a filthy version of Neil Young’s “Fuckin’ Up.”

As he left the stage, he assured the D.C. crowd he’d be back. “We’ll see you when the revolution happens, because it will be right here.”